U.S. Supreme Court. Photo: Mike Scarcella / NLJ

U.S. Supreme Court. Photo: Mike Scarcella / NLJHow Stephen Shapiro Helped Lawyers—and Reporters—Understand SCOTUS

In practice, Stephen Shapiro of Mayer Brown, founder of the firm's Supreme Court practice, applied and honed his knowledge with 30 oral arguments before the justices.

August 15, 2018 at 11:58 AM

3 minute read

Knowingly or not, most Supreme Court advocates have interacted with Mayer Brown partner Stephen Shapiro by poring through “Supreme Court Practice,” the tome he co-authored that tells how to navigate the arcane traditions, rules and preferences of the court.

The depth and seriousness of the book and of Shapiro himself makes his violent death on Monday, at the age of 72, all the more stunning. He spent his professional life quietly building a Supreme Court practice when such a thing was rare. In the book, he told his colleagues and adversaries how the institution works.

And in practice, he applied and honed his knowledge with 30 oral arguments before the justices.

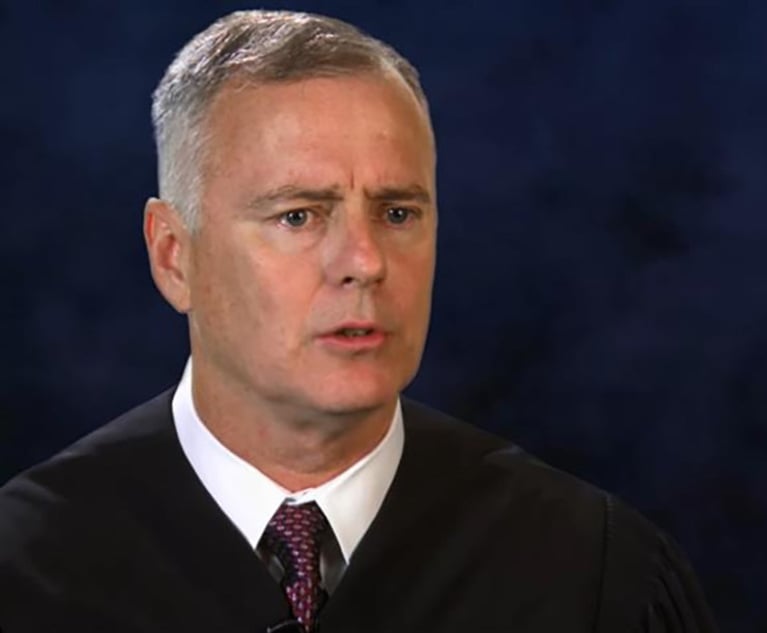

Stephen Shapiro

Stephen ShapiroShapiro also helped this journalist over many years by answering obscure questions about the court. Was it improper for justices to do their own research in cases, gathering information that could be inaccurate? No, Shapiro said, adding that the danger of occasional flubs is “greatly outweighed” by the benefit of letting justices “think and do research about the real-world aspects of matters before them.”

How important is the “Question Presented” page that starts off a Supreme Court brief? Surpassingly so, he said, calling it “the most important page in the entire document. It should be the colorful fly that irresistibly leads to a strike.”

Shapiro's colleagues, taking to social media Tuesday, mourned his death. Kannon Shanmugam, the Williams & Connolly appellate practice leader, called Shapiro ”as modest as he was brilliant” and noted that Shapiro “literally wrote the book on Supreme Court advocacy.”

Shapiro was an advocate for intense preparation, stating in an interview that he tried to spend a full month getting ready for a Supreme Court argument. Ironically, in the argument he made that I most vividly remember, he had only two days to prepare.

It was Keeton v. Hustler, a 1983 libel case that raised a jurisdictional issue involving Larry Flynt's racy magazine. Just before argument, Flynt fired his lawyer and told the court he wanted to represent himself.

Instead, the court recruited Shapiro, who had written an amicus brief on Flynt's side. “Forty-eight hours later, I argued the case before the Supreme Court,” Shapiro once recalled. His able argument was overshadowed when Flynt shouted obscenities at the justices. Flynt was arrested, and the court voted 9-0 against him.

It would have been hard to fault Shapiro for the loss.

Read more:

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trump's Solicitor General Expected to 'Flip' Prelogar's Positions at Supreme Court

Auditor Finds 'Significant Deficiency' in FTC Accounting to Tune of $7M

4 minute read

Texas Court Invalidates SEC’s Dealer Rule, Siding with Crypto Advocates

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Gibson Dunn Sued By Crypto Client After Lateral Hire Causes Conflict of Interest

- 2Trump's Solicitor General Expected to 'Flip' Prelogar's Positions at Supreme Court

- 3Pharmacy Lawyers See Promise in NY Regulator's Curbs on PBM Industry

- 4Outgoing USPTO Director Kathi Vidal: ‘We All Want the Country to Be in a Better Place’

- 5Supreme Court Will Review Constitutionality Of FCC's Universal Service Fund

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250