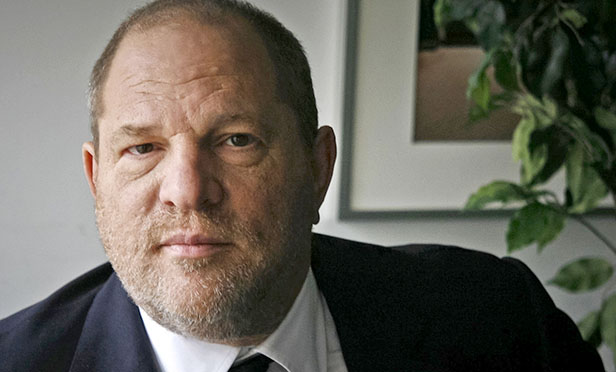

Weinstein Co. Asset Sale Averts Bankruptcy, but Clouds Remain Over Its Future

A group of investors on Thursday said that it had reached a $500 million agreement to buy the Weinstein Co., reviving a deal that just days before seemed to be dead, despite the high-profile intervention of New York state Attorney General Eric Schneiderman.

March 02, 2018 at 04:14 PM

4 minute read

A group of investors on Thursday said that it had reached a $500 million agreement to buy the Weinstein Co., reviving a deal that just days before seemed to be dead, despite the high-profile intervention of New York state Attorney General Eric Schneiderman.

The group, led by Maria Contreras-Sweet, agreed to purchase more than 90 percent of the embattled film studio's assets, including its television business and catalog of films, according to The Wall Street Journal. The buyers would pick up $225 million in Weinstein Co. debt and invest about $275 million to launch a new company, the paper reported Thursday night.

The agreement, for now, staved off what appeared to be an imminent bankruptcy and purported to establish a settlement fund for the victims of sexual abuse on the part of disgraced movie mogul and company co-founder Harvey Weinstein.

The agreement was also seen as vindication for Schneiderman, who in February sued the Weinstein Co. in New York state court, fearing that a sale could result in an unfair windfall for the company's executives while not adequately protecting victims.

The film producer has been accused of sexual harassment and assault by dozens of women. He has denied allegations of engaging in nonconsensual sex. He was kicked out of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in the wake of the scandal.

In a statement, Schneiderman said the Contreras-Sweet-led group, which included investor Ron Burkle, agreed to create a compensation fund and enact policies to protect employees from harassment and abuse. The deal, he said, would ensure that Weinstein Co. directors who supposedly turned a blind eye to Harvey Weinstein's behavior would “not be unjustly rewarded.”

“As part of these negotiations, we are pleased to have received express commitments from the parties that the new company will create a real, well-funded victims compensation fund, implement HR policies that will protect all employees, and will not unjustly reward bad actors,” Schneiderman said. “We will work with the parties in the weeks ahead to ensure that the parties honor and memorialize these commitments prior to closing.”

Schneiderman said that the lawsuit will remain active and his office's investigation would remain ongoing.

Schneiderman sued Weinstein Co. Feb. 11, using a broad provision of New York law that authorizes the state to file suit against a company for “fraudulent or illegal acts” perpetrated against its citizens.

However, experts said it also had the potential to scare off potential buyers, driving down the company's value and the assets available to Harvey Weinstein's victims. That, in turn, could lead the company to file for bankruptcy, which would slow litigation and leave it up to a judge to determine the relative order for the distribution of assets among the company's creditors and plaintiffs, and shareholders.

“The last thing they wanted were buyers getting scared off and leaving town,” said Eric Talley, a professor at Columbia Law School who specializes in corporate governance and finance.

Still, the company appeared earlier this week to be on the verge of bankruptcy after negotiations between the company and the buyers broke down Sunday night over disagreements on how to compensate victims, protect employees and hold executives accountable.

“We are disappointed that despite a clear path forward on those issues—including the buyer's commitment to dedicate up to $90 million to victim compensation and implement gold-plated HR policies—the parties were unable to resolve their financial differences,” Schneiderman spokesman Eric Soufer said in a statement on Monday.

But the turnaround came three days later, after the sides huddled at Schneiderman's office in hopes of finally reaching a deal. According to media reports, Contreras-Sweet and the talks included a settlement fund of up to $90 million to pay victims.

However, it remained unclear whether that total would be enough to adequately compensate all of the potential plaintiffs. While some civil cases have been filed, there has been no real accounting of damages, and it is not yet known how many victims will file suit.

“I just don't think we know the answer from publicly available information yet,” Talley said.

There also remains the possibility that Weinstein Co. shareholders will file derivative lawsuits if they think they were shortchanged on their original investment in the firm. Under the Caremark theory, investors could argue that Weinstein Co. directors should assume personal liability for corporate harm on the basis that they were aware of a systemic problem but failed to act.

However, the prospects for derivative litigation remain unclear given the Weinstein Co.'s status as a privately held firm.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Justice 'Weaponization Working Group' Will Examine Officials Who Investigated Trump, US AG Bondi Says

Lawyers Across Political Spectrum Launch Public Interest Team to Litigate Against Antisemitism

4 minute read

'Landmark' New York Commission Set to Study Overburdened, Under-Resourced Family Courts

Trending Stories

- 1With AI, What Changes Can Midsize Firms Expect?

- 2Saul Ewing Loses Two Partners to Fox Rothschild, Marking Four Fla. Partner Exits in Last 13 Months

- 3Eagles or Chiefs? At These Law Firms, Super Bowl Sunday Gets Complicated

- 4Former NY City Hall Official Tied to Adams Corruption Probe to Plead Guilty

- 5Wilmer, White & Case, Crowell Among the Latest to Add DC Lateral Partners

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250