Employment Bar Shaken by Ruling That Restricts Age Bias Protections

Days after it came down, the employment bar is still dissecting a complicated en banc ruling from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit that says older job applicants can't bring discrimination suits based on a theory of disparate impact.

October 12, 2016 at 03:04 PM

6 minute read

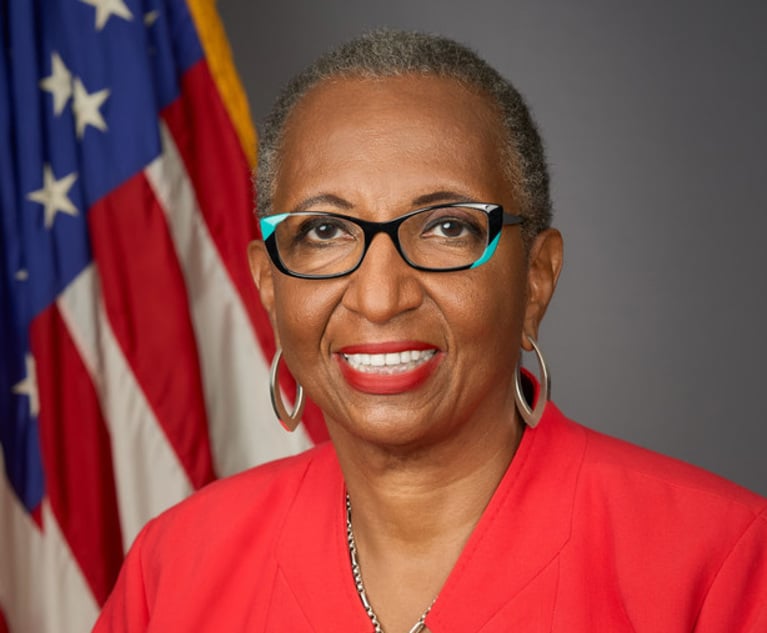

Eleventh Circuit Judge William Pryor Jr. discusses the U.S. Supreme Court, his path to the bench and other topics at a Federalist Society DC Young Lawyers Chapter event on July 16, 2015. Photo by Zoe Tillman/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL.

Eleventh Circuit Judge William Pryor Jr. discusses the U.S. Supreme Court, his path to the bench and other topics at a Federalist Society DC Young Lawyers Chapter event on July 16, 2015. Photo by Zoe Tillman/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL.

Days after the decision, the employment bar is still dissecting a complicated en banc ruling from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit that says older job applicants can't bring discrimination suits based on a theory of disparate impact.

In a fractured full bench decision, the court held, seemingly for the first time, that the key provision of the federal age discrimination law applies only to a company's employees and not to individuals who apply for job openings. The decision is a game changer within the Eleventh Circuit states of Alabama, Florida and Georgia and has some lawyers calling for Supreme Court review.

The majority opinion written by Judge William Pryor, rejected a potential mass action lawsuit against R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. over a hiring policy that allegedly gave preference to applicants with two to three years of job experience out of college and disfavored those with closer to a decade in the workforce. The company's guidelines provided to its hiring contractor, according to the ruling, said the greener group of workers “adjusts easily to changes.”

The decision sparked a vigorous dissent from Judge Beverly Martin and shocked lawyers who represent workers in discrimination claims. Companies can just put up a sign: “Those over 40 need not apply,” said veteran employment and civil rights lawyer Lee Parks of Parks, Chesin & Walbert of Atlanta. “It's a sad decision,” he said, adding he doesn't expect it to stand.

The question before the court was whether the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 allows a rejected job applicant to sue over a practice that has a disparate impact on older workers. Pryor was joined at least partially by seven other judges in holding that the disparate impact provision, unlike other pieces of the law, does not protect applicants, only employees.

The 76-page decision went deep into the tenets of statutory construction, parsing a provision that makes it “unlawful for an employer … to limit, segregate, or classify his employees in any way which would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee, because of such individual's age.”

Pryor, joined by Chief Judge Ed Carnes and Judges Gerald Tjoflat, Frank Hull, Stanley Marcus and Julie Carnes, focused on the phrase beginning “or otherwise,” deeming it a “catchall” that limits the section's reach. Judges Adalberto Jordan and Robin Rosembaum agreed with that part of the decision.

In a dissent joined by Judges Jill Pryor and Charles Wilson, Martin wrote that, if the majority is right, then the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and all other courts in the country have been wrong for 49 years.

She said the law protects two categories of individuals—those adversely affected in their employment as well as those deprived of employment opportunities. Martin pointed to the phrase “any individual” and said it was safe to assume Congress meant what it said. Plus, she wrote, an “individual” who can't get a job because of age is unlawfully denied any “status as an employee.”

“This perfectly natural reading is the one the EEOC has always used,” wrote Martin, who authored a panel opinion in the case in 2015 which called the statute's language ambiguous and deferred to the agency interpretation.

Writing separately, Rosenbaum addressed the dilemma and rebuked the EEOC for adopting what she called a flawed interpretation of the statute.

“This case is challenging,” she wrote, “because despite the clarity of the statutory language, the agency charged with administering the statute has, for nearly the past 50 years—through both Republican and Democrat administrations—consistently construed it in a way that conflicts with what appears to me to be the objectively indisputable meaning of the statutory language. That fact gives me serious pause.”

Martin took her colleagues to task on a second point, as well. The majority ruled that Richard Villarreal, the named plaintiff, waited too long to sue after RJR first rejected him in 2007 at the age of 49. Villarreal didn't take action until 2010, when a law firm contacted him and suggested R.J. Reynolds had discriminated against him because of his age. Villarreal then made five more applications for employment—all rejected—before lodging a complaint with the EEOC.

Martin argued that Villarreal had no way to know about the company's private preference for younger workers and his claims should not be time-barred. “The majority now tells us that secret discrimination won't be punished unless the victim tried to expose the discrimination himself, even if he had no reason to suspect anyone was discriminating against him,” Martin wrote.

The legal team representing Villarreal and others similarly situated is considering asking the U.S. Supreme Court to review the decision, according to one of the attorneys, John Almond of Rogers & Hardin in Atlanta. The team includes Berger & Montague in Philadelphia and two firms in San Francisco, Altshuler Berzon and Schneider Wallace Cottrell Brayton Konecky.

“We're just now in the process of coming to grips with the decision and procedural status,” Almond said Tuesday. “I think it's fair to say this isn't the last step in this case.”

R.J. Reynolds' defense team at Jones Day in Atlanta and Washington, D.C., did not respond to a request for comment.

The company has backing from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which argued that Congress intended to limit the protections afforded to older job applicants “because age is different than the other classifications protected from employment discrimination.” The chamber went on to argue that unlike other protected groups, older people had not faced a lifetime of discrimination. “Older workers today were younger workers yesterday.”

Georgia State University Law School Dean Steven Kaminshine, who teaches labor and employment law, agreed with Pryor's finding of an imperfection in the statute. But he suggested the hair-splitting debate over word meanings missed the big picture. “Personally, I think the court should have gone further and determined whether the outcome was rational and reasonable,” he said.

Harvard University law professor Noah Feldman panned the decision in a Bloomberg article headlined, “Subtle Age Discrimination Gets a Court's Blessing.” He urged the U.S. Supreme Court to take the case and “fix the bad literalism.”

Until then, Feldman concluded, “disparate impact age discrimination can flourish in the 11th Circuit.”

Katheryn Hayes Tucker can be reached at [email protected]. On Twitter: @KatherynHTucker

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Class Action Claims Amazon's Point-Based Attendance Policy Is Discriminatory, Suit Says

3 minute read

Trump Fires EEOC Commissioners, Kneecapping Democrat-Controlled Civil Rights Agency

Trump’s Firing of NLRB Member Could Spark Review of Supreme Court Precedent

Testing Legal Authority, Trump Fires NLRB Member, Leaving Panel Without Quorum

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250