Is the top end of the legal market finally ready for transatlantic consolidation?

Following the Eversheds Sutherland tie-up and the Norton Rose-Chadbourne talks, Chris Johnson looks at the prospects for more major UK-US merger deals

February 10, 2017 at 06:35 AM

7 minute read

The original version of this story was published on Law.com

The consolidation of the legal market across the Atlantic has been talked up for decades.

Any time there's a major deal between US and UK firms, people start heralding the onset of transatlantic merger 'mania', which is about the least appropriate word I can think of to describe what is usually a protracted, painstaking process.

Each time, the anticipated wave of follow-on deals fails to materialise. So far, the transatlantic merger trend has been more of a squeak than a big bang. Could that be about to change?

The recent marriage of Eversheds and Atlanta-based Sutherland Asbill & Brennan, and the news that Norton Rose Fulbright is in talks with Chadbourne & Parke – a deal that would finally give the global giant the New York presence it has long craved – has brought the issue back into sharp focus.

In this post-Brexit, post-Donald Trump world of uncertainty, forecasting is a game for the foolish and foolhardy. But I'll give it a go. Looking purely at large-scale transatlantic combinations, rather than the acquisition of smaller practices, I'd bet on there being a handful of additional deals in the coming years. But don't expect a glut.

For any individual firm, there will only be a reasonably small number of transatlantic targets with the right mix of practice areas and sectors, broadly comparable financial performance – particularly around rates and profitability – and, perhaps most importantly of all, a compatible culture. Scrub out the firms that have no international aspirations or interest in merging, and the shortlist becomes shorter still. It's like searching for a needle in a haystack made entirely of other needles. (Also: without extreme care, you're liable to get hurt.)

Secondly, without wanting to state the blindingly obvious, law firm mergers are incredibly difficult to pull off. At every stage, from finding a suitable candidate to actually getting the deal approved by partnerships that are generally risk and change averse, they are fraught with complications.

This is doubly true of transatlantic mergers, where firms face the complex and potentially costly issue of reconciling contrasting tax, accounting and partner compensation arrangements. Most large UK firms operate accruals-based accounting systems with a year-end of 30 April, and compensate partners via some form of lockstep. US firms, meanwhile, typically utilise cash-based accounting setups with a calendar financial year. They also tend to reward partners based more on individual merit.

A Swiss verein – a holding structure that allows member firms to join forces yet retain their existing forms – sidesteps or at least mitigates many of these hurdles, but serious challenges remain. (Almost every recent major cross-border law firm combination has been carried out via a verein, including those that formed Dentons, DLA Piper, Hogan Lovells, King & Wood Mallesons, Norton Rose Fulbright and Squire Patton Boggs.)

It is unsurprising, then, that while merger talks between firms are actually pretty common – at any one time, it's likely that some form of discussion is ongoing somewhere in the market – the vast majority never materialise. Even among those that make it to an advanced stage, the failure rate is still relatively high. Last year, Greenberg Traurig pulled out of its proposed tie-up with Berwin Leighton Paisner amid concerns about the London-based firm's practice mix, culture and management. And a deal between Hunton & Williams and Addleshaw Goddard was put on hold in August due to concerns over the Brexit vote.

There does now seem to be more interest among firms in transatlantic deals than ever before, however. And the more that actually go ahead, the more other firms are likely to follow suit, so as not to be left behind by newly expansive rivals.

One magic circle management partner told me that his firm is 'open-minded' about the prospect of a US merger

Combinations could also be driven by firms wanting to move while choice targets still remain, although we're a long way from the situation in Germany in the late 1990s, when international firms flooded the market and had to fight over a rapidly diminishing number of local practices. During an 18-month period, those local practices were almost all acquired by US and UK interlopers.

Mid-sized firms are under particular pressure to act, with many lacking the scale or specialisation to adequately differentiate themselves in an increasingly competitive market. Look across the US top 200 and you'll see many firms with hundreds of lawyers who are largely doing the same sort of work for the same sort of clients. That is not a viable long-term strategy. Smaller practices with fewer – if any – international offices are also less equipped to deal with the continued globalisation of legal services.

But perhaps the most significant question is the extent to which the elite firms will get involved. There has only ever been one transatlantic deal involving a white shoe or magic circle law firm: the merger between Clifford Chance and New York's Rogers & Wells in 2000. And that didn't exactly go well.

A merger could be one way for the magic circle firms to resolve their longstanding struggle to build scale in the US, where despite decades of investment, they remain largely peripheral players. Likewise, for US firms in London, where interest in growth remains high despite the UK's decision to leave the EU. There are already about 90 US firms with offices in London, collectively employing more than 6,000 lawyers. But most have failed to reach a critical mass in the UK. Excluding the products of large-scale transatlantic mergers, such as DLA Piper and Hogan Lovells, just 10 US firms have more than 100 lawyers in London, according to NLJ 500 data. Most have fewer than 60.

Such top-tier deals have always been considered unlikely, mainly due to an assumption that the magic circle would only be interested in the top Wall Street firms, which are significantly more profitable than their UK rivals and seemingly not interested in merging anyway. That may have been the case in the past, but the magic circle firms seem to have broadened their approach.

One magic circle management partner told me that his firm is "open-minded" about the prospect of a US merger and said there is "a lot of quality" beyond the white-shoe firms. And while the magic circle may lack the financial firepower of the top New York practices, you don't have to go too far down the Am Law 100 charts before the profitability gap begins to close.

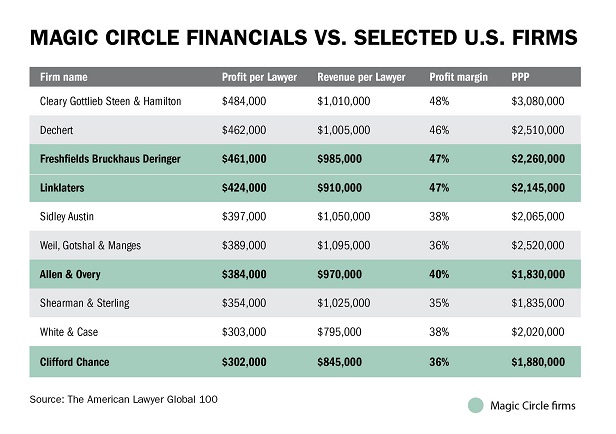

When viewed across a range of metrics, including profit margin, revenue and profit per lawyer (RPL and PPL), and profit per equity partner (PEP), they are in the same ballpark as firms such as Dechert, Sidley Austin, Shearman & Sterling and Weil Gotshal & Manges. And that's as measured in US dollars, even after an unfavourable currency conversion resulting from a historically weak British pound.

Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer's margin, RPL and PPL are actually within a few percent of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton – it is only distanced on PEP by virtue of having a larger equity partnership.

Despite the considerable strides being made in London by Latham & Watkins and White & Case, no single law firm has successfully established itself as a true market leader on both sides of the Atlantic. When viewed in that context, a transatlantic deal involving an elite American or British law firm could be a genuine game changer.

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Be Prepared and Practice': Paul Hastings' Michelle Reed Breaks Down Firm's First SEC Cybersecurity Incident Disclosure Report

Big Law Practice Leaders Gearing Up for State AG Litigation Under Trump

4 minute read

Deal Watch: Private Equity Dealmakers Make 2025 Predictions Amid Deal Resurgence

12 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250