Picasso Painting at Met Won't Return to Estate of Jewish Couple Who Fled Nazi Germany

The plaintiff claimed that her great-granduncle and aunt were forced to sell Picasso's "The Artist" under duress as they fled Nazi Germany and fascist Italy.

February 07, 2018 at 06:16 PM

4 minute read

The original version of this story was published on New York Law Journal

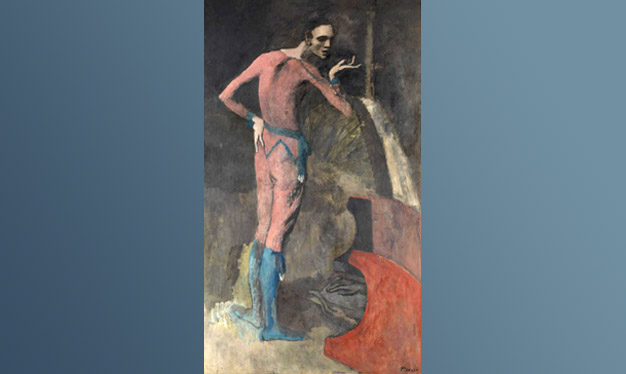

Picasso's “The Artist”

Picasso's “The Artist”

An attempt to see a Pablo Picasso painting hanging at the Metropolitan Museum of Art returned to the estate of a Jewish couple forced to flee Nazi Germany was stymied Wednesday.

U.S. District Judge Loretta Preska of the Southern District of New York granted the Met's motion to dismiss the amended complaint, filed in January by Swiss resident Laurel Zuckerman, that sought replevin of Picasso's “The Artist” painting and conversion damages of $100 million. Zuckerman is the heir to the estate of Alice Leffmann, who, along with her husband Paul, was forced to sell all possessions in order to flee anti-Semitic persecution first by the Nazis and then by the Italian fascists.

With money and time running out, the Leffmanns negotiated the sale in 1938 of their last prized possession through a dealer holding the painting in Switzerland. They ultimately secured $12,000 from a sale to Parisian art dealers Hugo Perls and Paul Rosenberg. The money would ultimately allow them to flee Europe for South America. They eventually settled in Switzerland after the war.

The painting was lent in 1939 by Rosenberg to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was then consigned for sale in 1940 to a private buyer, Thelma Chrysler Foy, who donated it to the Met in 1952. It has remained there ever since.

Zuckerman's amended complaint alleges that her great-granduncle and aunt were forced to sell the painting under Italian law principles of duress, and public order and morals. The Met moved to dismiss the claims, arguing, among a number of deficiencies, that under either Italian or New York law, duress was not adequately alleged, and that even under Italian public law and older laws there was no violation in the sale.

In granting the Met's dismissal of the amended complaint, Preska found that, on the issue of duress, there was, in fact, no difference between New York and Italian law. While Italian fascism may have driven the couple to sell, it was not directly the reason they were forced to sell and “[a] general state of fear arising from political circumstances is not sufficient to allege duress,” Preska wrote.

An attempt by Zuckerman to time her public order and morals argument to a post-war Italian law that sought to bring back goods sold as part of an anti-Semitic persecution likewise failed, Preska noted, because the sale occurred before the October 1938 cutoff date stipulated by the law.

The claims failed under New York law, most clearly because the defendants in the suit have to be at fault for causing the duress. Simple general economic pressures alone aren't enough as well under New York law, Presksa noted. No claims that Perls, Hugo or Rosenberg put undue pressure on the Leffmanns were being made by Zuckerman, nor any claim that it was fascist Italy, directly, that forced the sale. Preska pointed to years of negotiations between the Leffmanns and numerous parties before the sale of the painting that showed the couple attempting to leverage their position for the greatest gain.

Likewise, in a lengthy choice-of-law analysis over Zuckerman's claim that there is an outcome-determinative difference between the two sets of laws, Preska found that New York has the greatest interest in the litigation, considering the time the painting has been in the state. But as she previously noted, even under New York law, the claims fail.

Zuckerman's representation was led by Herrick Feinstein partner Ross Hirsh. In a statement, he said his client was disappointed in the court's decision, and planned to appeal.

In a statement, the Met said it welcomed the “thorough and well-reasoned decision” in the case. It stated that it considers all Nazi-era claims about works in its possession “thoroughly and responsibly, and that objects have been returned when evidence has demanded it.

“Here, however, as the court clearly explained, the painting was never in the hands of the Nazis and was never sold or transferred as a result of Nazi-era duress,” the museum said.

Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr partner David Bowker represented the Met in the case.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Securities Report Says That 2024 Settlements Passed a Total of $5.2B

3 minute read

Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

3 minute read

Landlord Must Pay Prevailing Tenants' $21K Attorney Fees in Commercial Lease Dispute, Appellate Court Rules

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Judge Finds Trump Administration Violated Order Blocking Funding Freeze

- 2CFPB Labor Union Files Twin Lawsuits Seeking to Prevent Agency's Closure

- 3Crypto Crime Down, Hacks Up: Lawyers Warned of 2025 Security Shake-Up

- 4Atlanta Calling: National Law Firms Flock to a ‘Hotbed for Talented Lawyers’

- 5Privacy Suit Targets Education Department Over Disclosure of Student Financial Data to DOGE

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250