DOJ's First Witness in AT&T Antitrust Trial Warns of 'Horribly Ugly' Deal if Merger Allowed

Justice Department lawyers say they're seeking to prove that AT&T's proposed merger with Time Warner will stifle competition.

March 22, 2018 at 03:13 PM

7 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

The U.S. Department of Justice's first witness in its challenge to AT&T's proposed merger with Time Warner testified Thursday, warning that if the two companies merge, they would have significantly more leverage in negotiations.

The antitrust trial, expected by many to be the most influential in decades, began in earnest Thursday with the testimony of Cox Communications Inc.'s Suzanne Fenwick, a content acquisition vice president, as well as opening arguments from lawyers for AT&T and the DOJ.

Members of the public and press lined up well before 7 a.m. Eastern Standard Time to enter the federal district courthouse in Washington, D.C., where the day's proceedings, delayed an hour due to weather, began at roughly 11:30 a.m. before a full courtroom—including AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson, Time Warner CEO Jeff Bewkes and Makan Delrahim, the head of the DOJ's Antitrust Division. U.S. District Judge Richard Leon is overseeing the trial.

Warnings of 'Egregious Fees'

DOJ lawyer Lisa Scanlon questioned Fenwick first, asking her to explain how her team negotiates with networks or groups of networks, to provide their content to Cox customers. Fenwick testified that DirecTV, which is owned by AT&T, is a fierce competitor to Cox, and that HBO, which is owned by Time Warner, is “by far” one of the most popular networks among Cox customers.

Fenwick also said Cox was concerned about what AT&T's acquisition of Time Warner would mean for the companies' content negotiations. She said it was likely Cox would be forced to either agree to a “horribly ugly” deal with “egregious fees,” or stop providing customers with “must have” channels, like Turner networks or HBO. She also said customers would leave Cox for DirecTV in order to watch Time Warner content.

Fenwick added there would be no incentive for either party to walk away from such a negotiation, as the networks would lose revenue and Cox would lose “must have” content.

At one point in the testimony, after Scanlon asked Fenwick to explain different issues that are discussed in these types of negotiations, Leon stopped Scanlon and called the lawyers to the bench. After some discussion, he called a brief recess, saying the lawyers needed to work out a “legal issue.” It was not immediately clear what that was.

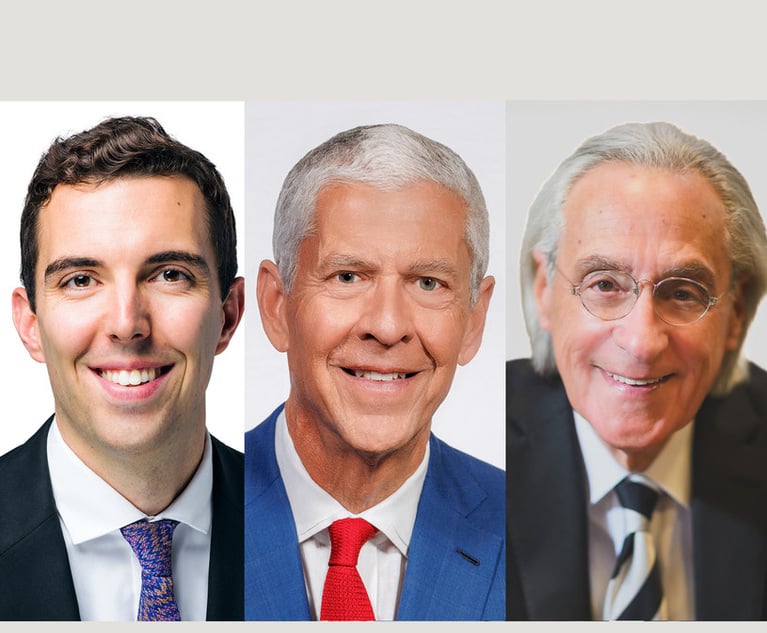

O'Melveny & Myers partner Daniel Petrocelli, the lead lawyer for AT&T and Time Warner, then attempted to discredit Fenwick. He asked if Fenwick, or anyone at her company, had done any sort of quantitative analysis to show how many customers would leave Cox if it did not show Turner content. She repeatedly replied that Cox had not, and that she did not know how many would leave.

He also asked Fenwick if she knew how many of the “most watched” television shows, sporting events and other programs in 2017 were from Turner networks. He added she must have “some idea,” given her prior testimony. She said she did not know.

Another major portion of Fenwick's testimony focused on an arbitration agreement AT&T offered to 1,000 competitors in November as a way to calm concerns about its proposed merger. Fenwick testified that the arbitration agreement is a “very one-sided agreement” and not a “helpful tool” for competitors.

The agreement would mean that if competitors cannot reach a deal to provide Time Warner content, the companies engage in “baseball style” arbitration, with each offering its own contract proposal for a private arbitrator to choose.

Petrocelli also asked about the agreement, and whether Fenwick or anyone at Cox discussed it with anyone at Turner. She said no, because the company did not consider it a “real” proposal. Fenwick did say she discussed the agreement with the DOJ.

Opening Statements

Parties were given 45 minutes each for opening statements in what is expected to be a six- to eight-week long trial. The government's lead lawyer, antitrust veteran Craig Conrath, was the first to address Leon, who did not say much throughout the opening statements and rarely if ever interrupted the lawyers.

Conrath told the judge that the proposed merger between AT&T, a service provider, and Time Warner, a content producer whose holdings include Turner Broadcasting System Inc., would harm competition by raising prices for consumers. He said the Clayton Act, under which the DOJ brought its lawsuit against the proposed $85 billion vertical merger last November, requires the court to make a prediction as to whether there's a reasonable probability the merger will harm competition.

Conrath argued that while corporate leaders at AT&T and Time Warner may think the merger will be a benefit, the facts suggest otherwise.

“Courts don't focus on intent,” Conrath said. “What they focus on is what the facts will be.”

Conrath said AT&T will use Time Warner content as a “weapon” to hinder competition because AT&T's competitors, like Charter or Comcast, need Time Warner content, like HBO shows or the National Collegiate Athletic Association's March Madness basketball tournament, to add and retain subscribers. He said expert analysis shows consumers will see a price increase of roughly five or six dollars a year if the merger is allowed to go through.

Conrath also argued that while AT&T claims its subsidiary, DirecTV, is losing business to internet companies like Netflix, most consumers actually subscribe to both online services and traditional pay-for-TV services. He gave the example of a game in the March Madness tournament last week, when a No. 16 seed, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, beat a No. 1 seed, University of Virginia, in a historic upset.

“There's no substitute for watching a game like that live,” Conrath said.

When Petrocelli addressed the judge, he reminded him the government has not challenged a vertical merger, in which two companies that don't compete, but rather are at different locations in the supply chain, since the 1970s.

He said vertical mergers that actually cause competitive harm are a “rare breed of horse,” and the one at issue is not rare. Petrocelli told the judge there was only one “clear-cut, just outcome” of the case: for Leon to deny the DOJ's request to block the merger. He added that while AT&T believes a price increase won't occur, a five- or six-dollar increase could not fit the description of substantially harming consumers.

Petrocelli said companies like Netflix and Google are “running away with the industry,” and that traditional pay-for-TV needs to keep up. He said Stephenson and others will testify about how changes at AT&T are intended to propel the company into the future, not stifle innovation, as the government argued.

“It's the government's theory, your honor, that is fundamentally stuck in the past,” Petrocelli said.

He also tried to poke holes in the conclusions of the government's expert, Carl Shapiro of the University of California, Berkeley. He said Shapiro's analysis of a potential price increase was based on flawed data, including a survey conducted by a company on behalf of one of AT&T's competitors.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Right Amount?: Federal Judge Weighs $1.8M Attorney Fee Request with Strip Club's $15K Award

Kline & Specter and Bosworth Resolve Post-Settlement Fighting Ahead of Courtroom Showdown

6 minute read

12-Partner Team 'Surprises' Atlanta Firm’s Leaders With Exit to Launch New Reed Smith Office

4 minute read

Morgan Lewis Shutters Shenzhen Office Less Than Two Years After Launch

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250