Move Over Moms, Male Lawyers Are Using Flextime Too

More widespread adoption by male attorneys of the benefit is expected to lift all boats—helping women lawyers juggle demands and attracting millennial attorneys less interested in working a constant grind.

March 28, 2018 at 01:45 PM

8 minute read

The original version of this story was published on The American Lawyer

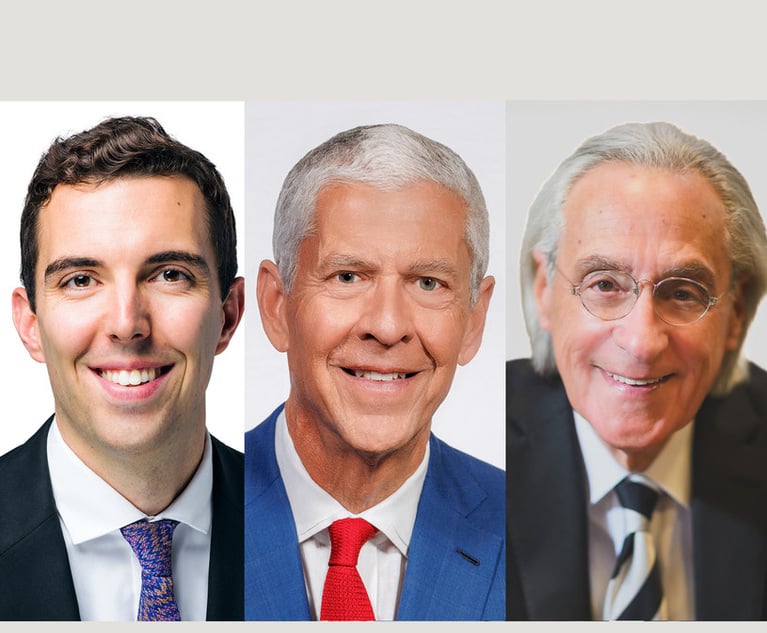

Erik Lemmon, right, his wife Laura Santerre-Lemmon, left, and their two children.

Erik Lemmon, right, his wife Laura Santerre-Lemmon, left, and their two children.Say the word “flextime” and most people think of reduced hours for working mothers. But a small, yet growing number of male lawyers are using lighter job schedules to strike the right work-life balance.

More law firms in recent years have incorporated flextime policies—especially reduced-hour schedules—to help with attorney retention. And women, more than men, have used the policies to balance their jobs with raising kids.

But more widespread adoption by male attorneys of the benefit is expected to lift all boats—helping women lawyers juggle demands and attracting millennial attorneys less interested in working a constant grind.

Foley & Lardner senior counsel Christopher King of Milwaukee recently went back to a full-time schedule after working at 90 percent reduced hours for 18 months. At the time he started, King and his wife already had a 5-year-old and 2-year-old, with a third baby on the way.

“We just got to a point as a family,” King recalled. “We said, 'This is crazy. Let's dial it back that 10 percent and see if it's enough.' It was a great fit both for work and for family.”

Previously, King only knew of female colleagues working reduced hours—but that's something he wants to change by advocating for his firm's reduced-hours policy.

“I think it's one of the things people worry about there being a stigma, but most people don't know—particularly if you roll back to 90 percent,” he noted. “I try to have the conversation with dads or to-be dads, because I think it's a very important time in their lives and children's lives and spouse's lives.”

One of King's colleagues is Casey Fleming, a reduced-hours partner at Foley, who said she's seen the impact as more male attorneys become keen to reduced schedules.

“I wish that wasn't the case, that, 'Oh, the men do it,' so it makes people more comfortable. But it really does,” Fleming said. “This is not 'mommy tracking.' It's 'everyone has their lives.'”

Firm culture will change faster if male attorneys insist that reduced-hours schedules are a condition of employment, said Sharon Rowen, director and producer of “Balancing the Scales,” a 2016 documentary about women in the law.

“If more people do it, no matter the gender, it will become a norm instead of the exception,” said Rowen, a partner in Rowen & Klonoski in Atlanta.

When firm leaders see male and female lawyers alike on reduced hours, it helps de-stigmatize the idea, she said. Today, women on flex or reduced schedules end up marginalized because many firm leaders think they're not as committed. That could change if more male lawyers take up reduced hours.

Like King, Erik Lemmon felt he was being stretched beyond capacity by the demands of work and home. About a year after his second child's birth, he was ready to leave Big Law because he felt he wasn't living up to his standards for being a partner to his wife and present for his kids, who are now 8 and 5 years old. Lemmon, a Holland & Hart associate in Denver who practices real estate law, chose to stay at the firm after a female colleague on flextime opened his eyes to his firm's reduced-hours policy. Since 2014, he's worked an 80 percent reduced schedule.

“I almost view it as something that saved my legal career, because I was essentially being forced to choose between hours and hours and hours at the law firm or doing what I wanted to do at home with my family and kids. I wasn't going to compromise on my kids, family and wife,” he said.

When he first started working reduced hours, Lemmon said he thought he was the only male lawyer who used the policy. He was annoyed to learn that other male lawyers did it too, but kept their schedules secret. In contrast, Lemmon decided to tell his story unabashedly.

“I have found people come out of the woodwork and ask me about it—men,” he said. “There's a stigma attached to it, whether you're male or female. There needs to be more examples out there of men doing it—still successful attorneys who do a good job.”

Rowen said that male lawyers of the millennial generation, who are less willing to sacrifice family time for heavy work demands, might make the difference in pushing reduced-hours schedules into the mainstream.

“Being there for family is something that men have often been denied, just as women have been denied fair access to a full career,” Rowen said.

Measuring the Trend

There's still a long way to go before reduced-hours policies become a norm in the wider legal profession. While many firms have written policies, lawyers don't widely use them.

Working Mother magazine scrutinized law firms' flextime policies, including reduced hours, when it released its 2017 list of Best Law Firms for Women. All 50 of the best firms offered reduced-hours benefits; however, only 9 percent of employees used the policy. Broken down by job title, 31 percent of counsel, 18 percent of staff attorneys, 7 percent of nonequity partners, 6 percent of associates and 4 percent of equity partners were working reduced hours.

Regarding gender, women were clearly still in the majority among reduced-hours lawyers, which included: 44 percent of female counsel and 23 percent of male counsel; 27 percent of female staff attorneys and 7 percent of male staff attorneys; 10 percent of female associates and 2 percent of male associates; 16 percent of female nonequity partners and 3 percent of male nonequity partners; and 11 percent of female equity partners and 2 percent of male equity partners.

But men are catching up at some firms in the reduced-hour ranks. At Hanson Bridgett in San Francisco, 23 percent of male nonequity partners were working reduced hours, according to Working Mother. At Crowell & Moring, 16 percent of male associates and 18 percent of female associates worked reduced hours; it was the only firm where male associates worked reduced hours in a rate in the double-digits.

The reason so few lawyers today take advantage of reduced-hours benefits is that many law firms still view a lawyer's availability as a proxy for commitment, explained Deborah Rhode, a Stanford Law School professor who directs its Center on the Legal Profession.

“They want lawyers to be there,” Rhode said. “There's resistance to keeping people on a leadership track who want that much flexibility.”

Still, it makes good business sense for firms in the long run, Rhode said.

“It costs a lot when lawyers drop out, so law practices need to get on board and I think those who do see they reap benefits in higher morale,” she said, noting that higher retention of lawyers is a main benefit to firms. “Doing a better job at this is critical to level the playing field for women.”

Some law firms have done a better job at incorporating reduced-hours schedules in their cultures.

“I didn't worry about it impacting my trajectory,” said Fleming, the Foley & Lardner equity partner. Even though she went on a 90 percent schedule in 2013, she still earned promotions right on time. “Junior attorneys watch people above them like hawks, and when it happens—they see people succeeding—it makes people more comfortable.”

Under most reduced-hours policies, lawyers can choose to take on anywhere between 60 to 90 percent of a full-time lawyer's annual billable-hour requirement. Many reduced-hours lawyers still work in the office Monday through Friday, often for normal business hours. Others might consistently take off one or two days a week. But reduced-hours lawyers say that their schedule relieves the pressure of having to make up their billable hours in situations where they leave work early to attend their kids' school events, drive a child to the doctor, take off to care for a sick baby, or attend to other family needs.

That flexibility has boosted Fleming's personal morale, she said.

“I regularly read at my kid's school on Fridays. My son just had a Japan unit at school, and I was able to go participate in that. It really is the day-to-day things,” Fleming said.

Downsides of Fewer Hours

While reduced-hours attorneys sing praises about their ability to be present with their families and free of billable hour worries, there are downsides too.

A lawyer's compensation is pro-rated according to the percentage of his or her flextime. Also, being on flextime can delay partnership, because it takes longer to develop the skills and register the experiences that the firm is looking for in partners, said Andrew Giacomini, managing partner in Hanson Bridgett in San Francisco.

Reduced-hours lawyers can still attain partnership—albeit more slowly, he said.

“If they know ultimately they can be successful and have a career at the company, then they stick to it,” Giacomini said.

Angela Morris is a freelance journalist. Follow her on Twitter at @AMorrisReports

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Right Amount?: Federal Judge Weighs $1.8M Attorney Fee Request with Strip Club's $15K Award

Kline & Specter and Bosworth Resolve Post-Settlement Fighting Ahead of Courtroom Showdown

6 minute read

12-Partner Team 'Surprises' Atlanta Firm’s Leaders With Exit to Launch New Reed Smith Office

4 minute read

Morgan Lewis Shutters Shenzhen Office Less Than Two Years After Launch

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250