Should Your Firm Match Milbank?

A cold-hearted look at market data and dynamics suggests firms would do well to approach the incipient round of salary increases extremely thoughtfully

June 07, 2018 at 10:07 AM

10 minute read

No one wants to take a 6 percent hit to 50 percent of their cost structure in the 107th month of an economic expansion that feels increasingly precarious. At the same time, no one wants hordes of disgruntled and distracted associates, embittered by perceived iniquities, wandering the hallways. So, when Big Law's executive committees sit down on Monday morning, which firms should match Milbank's move to a $190,000 starting salary? For those that do, how should they do it?

No one wants to take a 6 percent hit to 50 percent of their cost structure in the 107th month of an economic expansion that feels increasingly precarious. At the same time, no one wants hordes of disgruntled and distracted associates, embittered by perceived iniquities, wandering the hallways. So, when Big Law's executive committees sit down on Monday morning, which firms should match Milbank's move to a $190,000 starting salary? For those that do, how should they do it?

Deciding on a salary increase

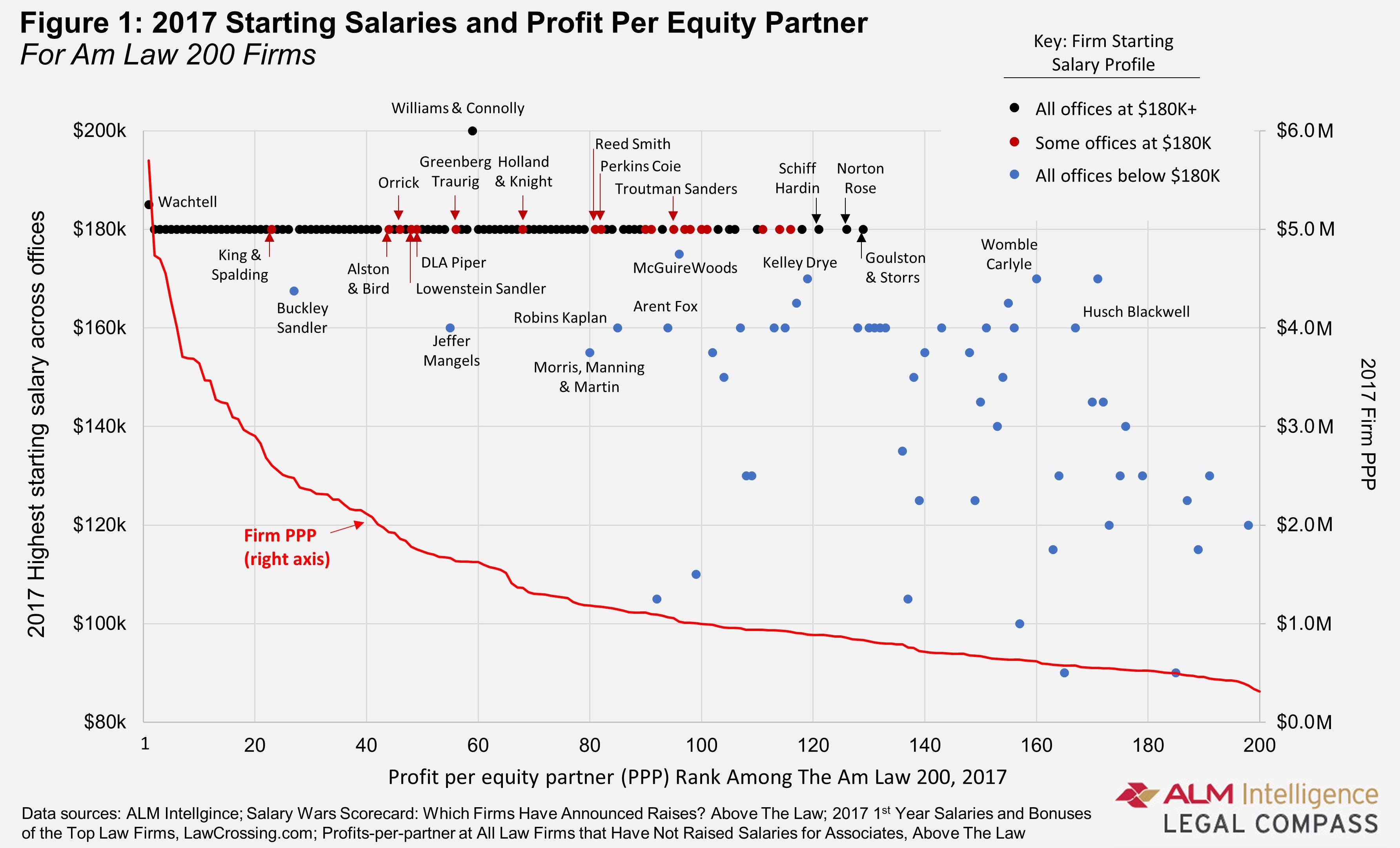

Let's set the context with some data. Figure 1 shows the starting salaries (before the unfolding increases) of the Am Law 200 ordered by profit per equity partner (PPP). The firms are grouped in three buckets: those with a $180,000 starting salary across all, some, or no offices; (the starting salary plotted is the highest across all a firm's offices). Also shown is firm PPP (the curve). The figure shows the top 120 firms are paying the same for their associates across a six-fold difference in firm PPP. This is what you see for a commodity raw material in a manufacturing industry, where the commodity is homogenous and interchangeable across all buyers. The data would imply that the 14,000 associates at the 20 most profitable firms provide the same service as the 45,000 associates at the next 100 most profitable firms. I'm skeptical. I'm sure the associates at these firms are good people and fine lawyers; I'm equally confident they're not fungible with the associates at Wachtell.

What's going on? A small piece of it is the Harvard junior faculty phenomenon. Harvard is infamous for under-paying its junior faculty whom it has no problem attracting given the institution's status. The same discount applies in consulting where starting salaries at the elite firms (The Boston Consulting Group, McKinsey) are below those at the legacy accounting firms. This would explain why the top 10 or so firms can underpay relative to the selectivity of their associates; it doesn't explain why firms ranked 10 to 120 should pay the same salary rate. Possible explanations for this include misinformation and vanity. The misinformation is that firms are constantly being told the market is bifurcating into haves and have-nots; paying below the top rate is acknowledging you're in the latter, downward spiraling, tier. As Nick Bruch of ALM Intelligence and I have demonstrated, no such separation is happening; the bifurcation notion is useful to consultants and headhunters and thus is proving hard to kill. The vanity explanation is that partners, even at firms ranked 60 to 120 by PPP, want to feel they're at elite firms. Their self-esteem is bolstered by paying their associates the same as elite Wall Street firms do. It's a high-priced route to healthy self-worth; alternative routes (mindfulness, exercise, a Rolex?) might be better value. Amateur psychoanalysis aside, the real culprit may be creeping “keeping-up-with-the-Joneses”: the top firm pays the increase; the second-to-top feels obliged to follow the top firm; the third firm feels obliged to follow the second, and on it goes. Each individual decision is rational; the cumulative result is insane.

Whatever the reasons for so broad a swathe of firms treating their associates as a homogenous commodity, firms should try to find a means to end it. They have two obvious levers: adopt the increases in only some offices, and demure on the increase entirely. The precedent for the former is well established. For the 2016 increases, the fault line was Atlanta, the 10th largest metropolitan area by GDP. The three firms with the largest number of lawyers in that city—King & Spalding, Alston & Bird, and Troutman Sanders—did not go to $180,000 there although they did in other cities. We've already seen demarcation by metropolitan area in the nascent round of increases: Proskauer, who announced an increase to $190,000 within 24 hours of Milbank's move, did not match Milbank in Florida, Louisiana, or New Jersey. They were not assailed for this by Above the Law, the arbiter for all that is just in the mind of the Big Law associate; indeed, it went entirely unremarked upon.

Atlanta held last time, so presumably will hold again this time. But can the fault line be moved to a bigger city? One market that really shouldn't move this time is Houston, the 6th largest metro area. Unlike in 2016, the local economy is stagnating. The three firms with the largest number of lawyers there—Vinson & Elkins, Norton Rose Fulbright, and Baker Botts, are of profitability levels (ranked 30th, 126th, and 47th by PPP, respectively) where the salary increase would be keenly felt by partners. Might they take a pass? Of course, this would require that Houston and Dallas operate at different cost structures—Dallas is the fourth largest metro area and growing strongly. But such separation is not impossible. It's helpful that the big three firms in Dallas are a different group—Haynes & Boone, Thompson & Knight, and Winstead. Plus, inter-metropolitan relations have been difficult since the eponymous TV show misappropriated from Houston to Dallas its rightful global renown as the center of the U.S. oil business.

Another large metro area one could see not moving is San Francisco (7th largest, immediately behind Houston). The two firms with the largest number of lawyers there are Morrison & Foerster and Fenwick & West; they rank 50th and 65th by PPP, respectively—well below where a rational dividing line could be established. The metro areas ranking immediately below Atlanta—Seattle, Miami, and Detroit—would seem separable from the major markets and thus could be expected to hold back on any increase. Perkins Coie and Davis Wright Tremaine hold the keys to Seattle; Greenberg Traurig, Akerman, and Holland & Knight to Miami; and Honigman to Detroit.

Increasing starting salaries in only major markets meets resistance from the managing partners of smaller market offices. It's tempting to yield to this push back, especially if these offices are relatively small. However, there is one situation in which one shouldn't yield: that where the smaller market office has a lower billing rate structure. It simply beggars belief that a market is major for cost (associate salary) and secondary for price (billing rate). If this margin misalignment has crept in through, say, recent office openings, then this round of increases presents an opportunity to fix it.

While expanding the number of metro areas that don't increase salaries is helpful, what the market really needs is for a group of medium-high profitability firms to take a stand and simply demure. The most likely contenders for such leadership may be King & Spalding, Alston & Bird, Orrick, Lowenstein Sandler, DLA Piper, Greenberg Traurig, and Holland & Knight—these are the firms who moved to $180,000 in only some offices last time. It would take some deft communication, something like: “we believe the increase would be poorly received by clients; we don't want to have the kinds of hours targets that support these salaries; we're following the advice we'd give to clients of not adding to fixed costs at this point in the economic cycle; instead, we are committed to increasing appreciably our annual bonuses (assuming activity continues strong through year end)”. It would also take restraint by peer firms from seizing the opportunity for shallow, ultimately self-harming, one-upmanship.

An important inference from this view of how salary increases will unfold is that the firms to watch are not the heavily-tracked big names; rather it's the mid-to-high profit firms and lesser names with the deep regional presences. Further, there are huge interdependencies—many firms will want to watch what lots of other firms do before deciding. It's going to take some weeks to play out. It could create a nightmare scenario for firms whereby they endure the cost hit of raising comp, but do so in a way that garners them no goodwill with associates. An option executive committees should consider: announce now to associates that you're watching the market closely, are committed to being competitive on compensation, are waiting to see more detail on how the market evolves, and that any changes you make will be back-dated to July 1st. (This last element is critical).

Pitfalls for those that do increase salaries

Even if a firm decides to go with the increase, the challenges don't end. In the realm of communications, it's not helpful to say you're going to tie the salary increase to higher hours requirements for bonuses. Or to say you'll implement the increase on July 1 and then, as one firm did last time, follow up with a communication on July 1 deferring implementation to October 1 citing “administratively ease”; (the firm later recanted). Salary increases delivered begrudgingly cost the same amount; the only difference is they garner no goodwill.

Many firms will be tempted to offset the salary increases with billing rate increases. This is tricky. Most law firms today have an inverted markup structure: their markup—the amount by which hourly billing rates exceed associate compensation costs (converted to an hourly equivalent)—is highest for the least experienced associates; normal businesses charge a higher markup on their highest value products and services. The inversion is caused by a reluctance to raise partner billing rates, making them an effective cap on senior associate rates and causing a bunching up of rates through the pyramid. It's insidious because keeping partner rates low constraints profitability and hiking junior associate rates irritates clients.

The best way to offset the hit to profitability is to increase leverage. As Bruch and I described recently, delegation still has a long way to go in law firms, and is a powerful driver of profitability. Curiously, holding back on partner billing rates makes it harder to raise leverage—part of the reason some partners push back on raising their rates is they feel some of the work they do is not truly partner level and hence shouldn't be billed at full partner-level rates. Just another reason to raise partner rates.

There is a tide in the affairs of law firms

The weeks ahead have the potential to be a watershed in the annals of Big Law. The anachronistic homogeneity of associate compensation could finally be broken. Its demise will help firms not only this year and through the next downturn, but it will provide for more concrete economic fundamentals in the decades ahead. Be calm, be thoughtful, be resolute.

Hugh A. Simons, Ph.D. is formerly a senior partner at The Boston Consulting Group and chief operating officer at Ropes & Gray. He welcomes readers' reactions at [email protected]

More information on the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program can be found here.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trending Stories

- 1Morgan Lewis Says Global Clients Are Noticing ‘Expanded Capacity’ After Kramer Merger in Paris

- 2'Reverse Robin Hood': Capital One Swarmed With Class Actions Alleging Theft of Influencer Commissions in January

- 3Hawaii wildfire victims spared from testifying after last-minute deal over $4B settlement

- 4How We Won It: Latham Secures Back-to-Back ITC Patent Wins for California Companies

- 5Meta agrees to pay $25 million to settle lawsuit from Trump after Jan. 6 suspension

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250