Herb Rubin, Who Argued 'World-wide Volkswagen,' Isn't Ready to Retire at Age 100

You know Herb Rubin. He argued that U.S. Supreme Court case you analyzed in law school.

August 27, 2018 at 03:33 AM

6 minute read

The original version of this story was published on New York Law Journal

Herb Rubin is a 100-year-old attorney who still practices. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ

Herb Rubin is a 100-year-old attorney who still practices. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ

You know Herb Rubin. He argued that U.S. Supreme Court case you analyzed in law school. World-wide Volkswagen Corp. v. Woodson, 444 U.S. 286 (1980), swung jurisdictional issues in defendants' favor. After that, plaintiffs could no longer justify suing in a jurisdiction that wasn't integral to the case.

That was nearly 40 years ago.

Fast-forward to 2018 and you can still meet the Herzfeld & Rubin name attorney in the flesh (There hasn't been a Herzfeld at the firm since 1960). Perhaps at a bar association meeting or the Jewish Lawyers Guild or his 100th birthday party at the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

If you attended the birthday gala—and by the family's count that included 25 Supreme Court justices—maybe you thought it was supposed to mark the end of his career. But you'd be mistaken.

“I'll work as long as I can get here,” he said during an interview at his Broad Street office overlooking the Statue of Liberty. “If I can no longer drive, I'll have to take an Uber.”

The regulars in New York City's legal community say he seems to be everywhere.

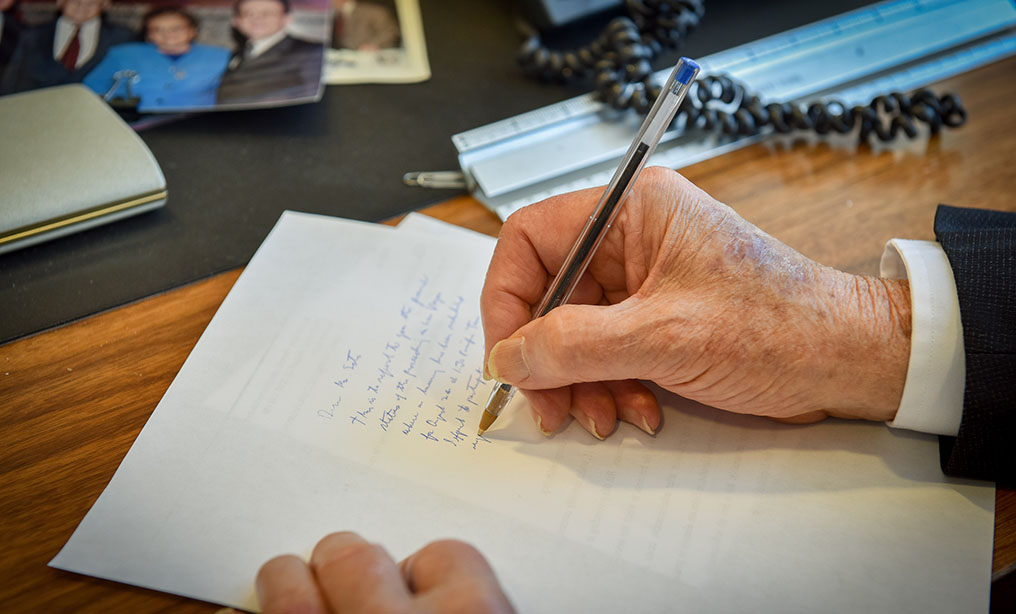

Herb Rubin drives himself to work and writes his briefs and notes by hand. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ

Herb Rubin drives himself to work and writes his briefs and notes by hand. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ“Herb is ubiquitous,” said Mark Zauderer of Ganfer Shore Leeds & Zauderer. “At just about every legal event I attend, when I turn around, Herb is there chatting with his longtime friends and colleagues. It's inspiring to see that a lawyer's career can extend for so many decades.”

David Saxe, a former associate justice for the Appellate Division, First Department, recalls seeing Rubin argue cases well into his nineties “and he was always a well-prepared highly-credible advocate and it was amazing to watch him argue a case.”

Rubin has made some concessions to age, of course. He uses a walker and a hearing aid, leaves work every day by 4:30 p.m. to avoid the worst of the Manhattan traffic and hasn't appeared in court for the last couple of years. But, just last Thursday, he was in his office handwriting a brief. (Yes, he still does handwrite briefs!)

A full-time lawyer over the age of 100 is a rarity in New York.

The state has 1,488 registered attorneys who are over the age of 90 but only 38 over the age of 100, according to the Office of Court Administration. Only 26 of them still live in the state, and most are likely retired or semi-retired. The oldest attorney paying the fee this year was 104.

When The New York Times looked for practicing New York attorneys over the age of 90 in 2010, it found only a handful. In its article, “Senior Counsel, Very Senior Counsel,” Rubin, who was 91 at the time, told the Times, “Certainly, there are things that I should be remembering that I wish I could remember a lot faster. But in terms of being able to analyze a case and to figure out the theory under which we should proceed and recall precedents which will be helpful, certainly, I can do that.”

And, he says, that's still true today.

Herb Rubin with Eleanor Roosevelt, left, and with Rudy Giuliani. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ/File

Herb Rubin with Eleanor Roosevelt, left, and with Rudy Giuliani. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ/FileRubin graduated from NYU Law School more than 75 years ago. After law school, he joined a firm with 85 lawyers, which was considered big in the 1940s. He was there only a short while because he was drafted and became a military lawyer in the Signal Corps, part of the U.S. Army. He was stationed for a time at Fort Monmouth in New Jersey.

While in law school, he met and married Rose Luttan, who would later become a state Supreme Court justice. The couple had three children and so many grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren that Rubin now has trouble keeping track. Rose died in 2016 after 75 years of marriage.

Rubin's eyes twinkle and his whole face lights up when he speaks about his grandson, Tommy, who followed in his footsteps and is now a deputy counsel at a high-tech firm. When Tommy was at Harvard Law, he somehow let it slip that his grandfather argued World-wide Volkswagen in front of the U.S. Supreme Court. The case was in their textbooks, and the professor was impressed.

Recalling the case, Rubin said, “The argument we had to make was an uphill argument. Our theory was the courts weren't there for forum-shopping.”

The case involved an automobile purchased in New York that was involved in an accident in Oklahoma. Volkswagen argued Oklahoma's jurisdiction over the manufacturer and retailer would violate the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The decision in Volkswagen's favor began to reverse the idea that plaintiffs could bring suit in any jurisdiction, no matter how tenuous the connection.

“The way in which the cases in personal jurisdiction seemed to be heading before Volkswagen was a more loosey-goosey approach to jurisdiction that would take into account all kinds of factors,” said Saxe, who's now a partner at Morrison Cohen. “But this case absolutely returned the analysis that minimum context be established first before you got into any other factors. So it was really a return to yesteryear.”

In the ensuing years, Rubin has argued cases in the Second, Third, Fourth, Sixth, Eighth and Ninth Circuits. He has met Eleanor Roosevelt and Rudy Giuliani. More recently, in Daimler AG v. Bauman, 134 U.S. 746 (2014), his firm submitted an amicus brief on behalf of foreign automobile manufacturers.

In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Daimler cannot be sued in California for injuries allegedly caused by its Argentinian subsidiary when the events took place entirely outside of the United States, further limiting general jurisdiction.

The message, Rubin said, is that “the U.S. shouldn't be a kind of dumping ground for lawsuits for things that happened out of the U.S.”

Herb Rubin in his office at Herzfeld & Rubin, a firm he helped start in 1948. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ

Herb Rubin in his office at Herzfeld & Rubin, a firm he helped start in 1948. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Statute of Limitations Shrivels $5M Jury Award to Less than $1M, 8th Circuit Rules

4 minute read

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute read

Arizona Board Gives Thumbs Up to KPMG's Bid To Deliver Legal Services

Goodwin to Launch Brussels Office With Quinn Emanuel Antitrust Partner

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250