ALSPs: Already Here & Looking Upmarket

Shifting more complicated workstreams to alternative legal service providers (ALSPs) may be the next tectonic shift in the legal market.

September 20, 2018 at 09:01 AM

11 minute read

Traditionally, ALSPs have been regarded as opportunities for labor arbitrage, typically in margin-compressed practice areas of limited complexity. Reduced quality is (wrongly) considered the tradeoff for low-cost labor. “The idea that ALSPs can only support 'simple' workstreams is just not true… we continue to test the boundaries on what our ALSPs are capable of… we are well beyond using them just for the routine work,” says Chris Chaffin, Vice President (Legal), Corporate Securities and M&A; Head of Legal Operations McAfee, a leading computer security software company. McAfee uses ALSPs to support contract management, M&A diligence, revenue related contract abstraction work, an ongoing, large-scale, legacy migration project and compliance reviews of marketing and product releases.

Traditionally, ALSPs have been regarded as opportunities for labor arbitrage, typically in margin-compressed practice areas of limited complexity. Reduced quality is (wrongly) considered the tradeoff for low-cost labor. “The idea that ALSPs can only support 'simple' workstreams is just not true… we continue to test the boundaries on what our ALSPs are capable of… we are well beyond using them just for the routine work,” says Chris Chaffin, Vice President (Legal), Corporate Securities and M&A; Head of Legal Operations McAfee, a leading computer security software company. McAfee uses ALSPs to support contract management, M&A diligence, revenue related contract abstraction work, an ongoing, large-scale, legacy migration project and compliance reviews of marketing and product releases.

While the cost-reduction mandate is the impetus for rethinking the inputs, corporate clients are finding improved quality of outputs is achievable when you decide to re-engineer how legal services are delivered. The promise represents the holy grail of legal service innovation: cheaper, faster, and better.

But is that promise attainable?

The “Inside Counsel Revolution”: Where It All Begins

The in-house counsel movement itself started as an exercise in labor arbitrage. Law departments found they could hire the same lawyers to do the same work the same way at materially lower cost per capita. “House counsel” was originally a term of disparagement. Before what former GE General Counsel Ben Heinemann termed the “inside counsel revolution,” in-house counsel were seen, and treated, as administrators whose primary purpose was to funnel work to law firms, where the 'real' lawyers resided. No more.

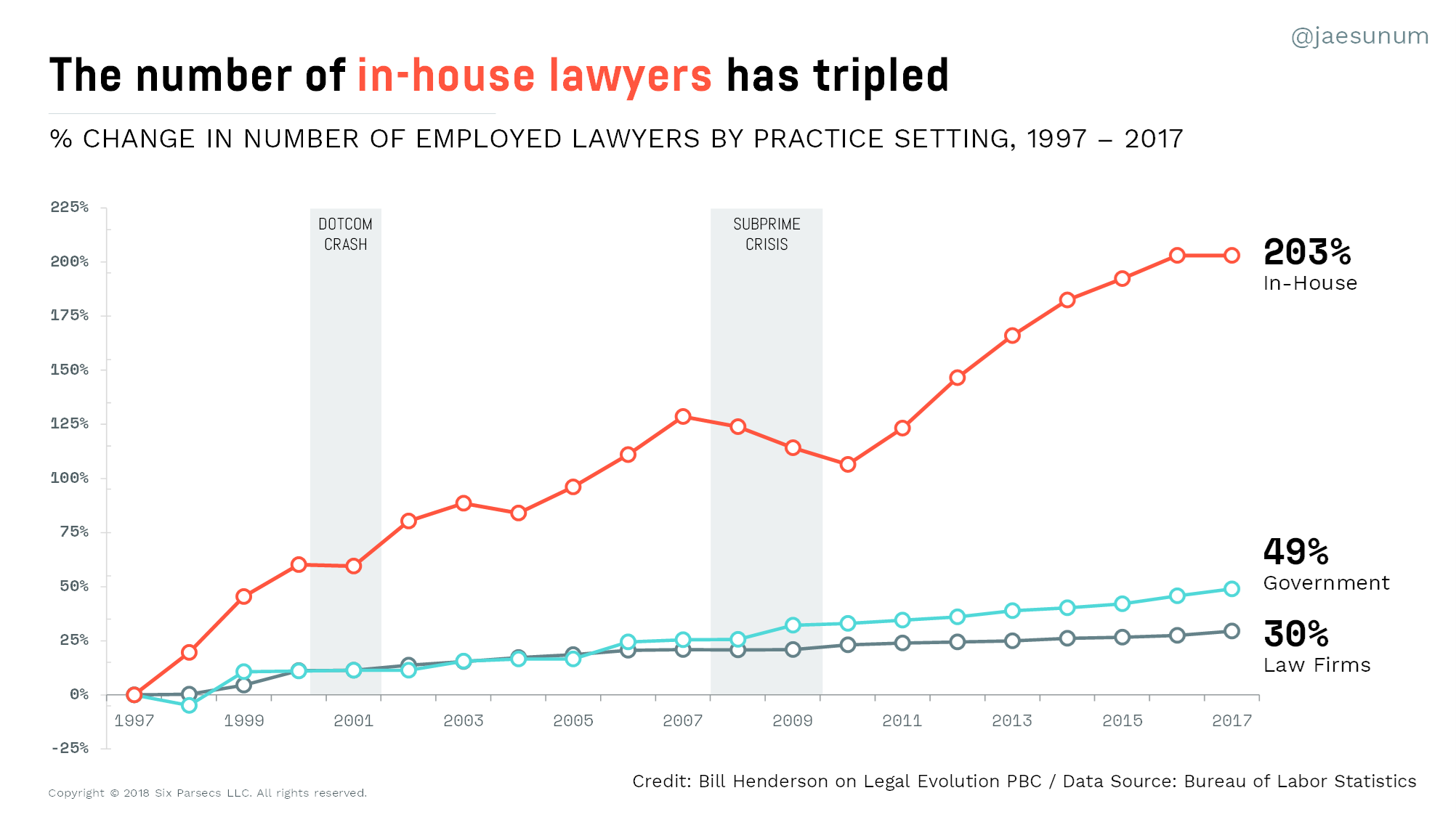

Since the late 1990's, in-house departments have grown at seven and a half times the rate of law firms. In the United States, there are now more in-house lawyers than lawyers in the domestic offices of the Am Law 200.

Insourcing not only changed lawyers' roles but also the way legal services are delivered. Embedded in the enterprise and fully invested in its success, business-first in-house counsel have found ways to cut costs and add business value—e.g., strategic advice, prevention—that extend well beyond being a cost-effective alternative to outside counsel.

A Ceiling on Insourcing?

As large as some law departments have become, there is likely a ceiling on their long-term scalability. In his newest book, Tomorrowland, famed legal market commentator Bruce MacEwan of Adam Smith, Esq. observes, “I doubt that in-house law departments will grow to the sky. The dynamic has tended to be one of oscillation, not steady expansion… At some point the GC's budget gets the (usually new) CFO's attention and the department is drastically pruned on the grounds that 'having a law firm under our roof is not a core competence.'”

Apart from the scrutiny from Finance, the legal supply chain extends outside the corporation for a real reason. Outside counsel exist to address a sourcing challenge facing nearly all corporate legal functions: the peak load problem. Demand for legal expertise (particularly the truly specialized and actually differentiated sort) tends to be unstable, spiky and varied.

Seen through that lens, the insourcing vs. outsourcing decision isn't, or at least shouldn't be, solely about the economics. The real job-to-be-done for corporate counsel in strategic sourcing is appropriate resource matching. In turn, this requires deep and current understanding of the needs of the company as well as the design and management of the optimal mix of delivery models to meet them.

The Legal Operations Boom

As legal departments reach their natural size limits, legal operations has grown as a discipline to build systems that leverage the legal expertise of existing resources through process and technology. Getting away from the legal market's traditional practice of measuring productivity in hours (more hours = more productivity) the legal ops mindset measures productivity in yield (more for less).

Both the Association of Corporate Counsel Legal Operations Section and the Corporate Legal Operations Consortium (CLOC) date back only to 2015—a year in which legal operations personnel doubled. Now, more than half of in-house departments have some form of legal operations.

Legal operations professionals represent the next step toward insourcing maturity: law departments are turning to legal operations to grow for scale, not size. ALSPs are the natural partner for legal departments that are operations focused and bringing a systems-oriented approach to legal services delivery.

The Theory for ALSPs Absorbing More Work

ALSPs are purpose built for managed-service relationships. The capital structure of ALSPs incents investments in infrastructure and technology. Patient money, in turn, permits business models focused on long-term relationships that become organically sticky due to the tailored nature of the managed services.

For ALSPs to maintain these long-term relationships, they focus first on expertly designed processes—far more stable than individual expertise. As Deming famously said, “If you can't describe what you are doing as a process, you don't know what you're doing.” ALSPs are premised on their ability to unpack and re-engineer processes for legal service delivery. Process is their identity. As law departments continue to embrace systems thinking, they find willing and able partners in ALSPs.

In theory, ALSPs are the next step in the evolution of legal service delivery. In practice, many law departments are already there. “Like the businesses we serve, law departments have to innovate to deliver superior results within resource constraints. Systems built around managed services are an important piece of our strategy to cost-effectively address the legal dimensions of business objectives,” says Aine Lyons. Lyons is Vice President & Deputy General Counsel, Worldwide Legal Operations, at VMware, where she uses an ALSP for M&A diligence, contract lifecycle management and to conduct open source reviews—work previously done in-house or sent to brand-name law firms.

ALSPs Are Built to Compete – for the Long Haul

While it is correct to observe ALSPs are more systems driven than personality driven, there is an attendant misimpression that ALSPs are bereft of the legal talent that walks the halls of Big Law.

Take QuisLex, a full-service legal process outsourcer. The company was founded by attorneys hailing from some of the best-known names in Big Law: Skadden Arps, Shearman & Sterling and Sidley Austin. Their Senior Vice President for Strategy & Client Services is Joseph Polizzotto, a former Cadwalader attorney served as general counsel at Lehman Brothers then at Deutsche Bank Americas. The litigation and transactional services lines are led by former practitioners who bring to Quislex deep expertise and experience in their respective areas: Vice President Philip Algieri started in Skadden's antitrust department while Executive Director Chase D'Agostino moved from Simpson Thacher to manage commercial contracts and supply chain compliance processes at Colgate-Palmolive.

Alex Hamilton was the co-Chair of Latham & Watkins' global Technology Transactions Group. Now, he is the Co-Founder and CEO of Radiant Law, a UK-based NewLaw firm that utilizes proprietary technology and a low-cost center in South Africa to assist its clients in creating, negotiating, and managing commercial contracts. Hamilton believes that ALSP have access to plenty of talent given “the number of ex-partners and other senior lawyers available in the market to work on projects, who prefer this to operating within traditional firms.”

Ray Bayley, the CEO and Co-Founder of the global legal services firm Novus Law agrees, “The vast majority of our lawyers have practiced in the Am Law 200,” says Bayley, whose firm primarily examines and analyzes evidence and other case-related materials to organize and prepare legal work product for disputes and investigations. “At one time, we worked hard to attract this kind of talent. Now, they seek us out.”

With highly credentialed and experienced lawyers in senior positions at ALSPs, it is no wonder we are seeing expanded capability to unpack, unbundle, and re-engineer processes for workstreams that used to be considered too complex for outsourcing. In its earliest days, process-driven approaches to legal service innovation focused primarily and sometimes solely on the mechanics of service delivery. Now, ALSPs are laser-focused on the substance of the legal risks and options at hand: they are willing and able to learn the content – as a necessary step to deploy legal expertise for scale, not hours.

Anecdote Trending Toward Evidence

Recently, several substantial ALSP arrangements have garnered press coverage. Just in the past year, PwC absorbed GE's tax specialists. UnitedLex, in many respects, became the DXC law department. And Elevate joined forces with Valorem to displace most of what Univar spends on outside counsel.

These deals are intriguing. But, reminiscent of Continental Bank axing its law department in favor of Mayer Brown in 1991, there is not sufficient volume to distinguish interesting outliers from a meaningful market-wide trend.

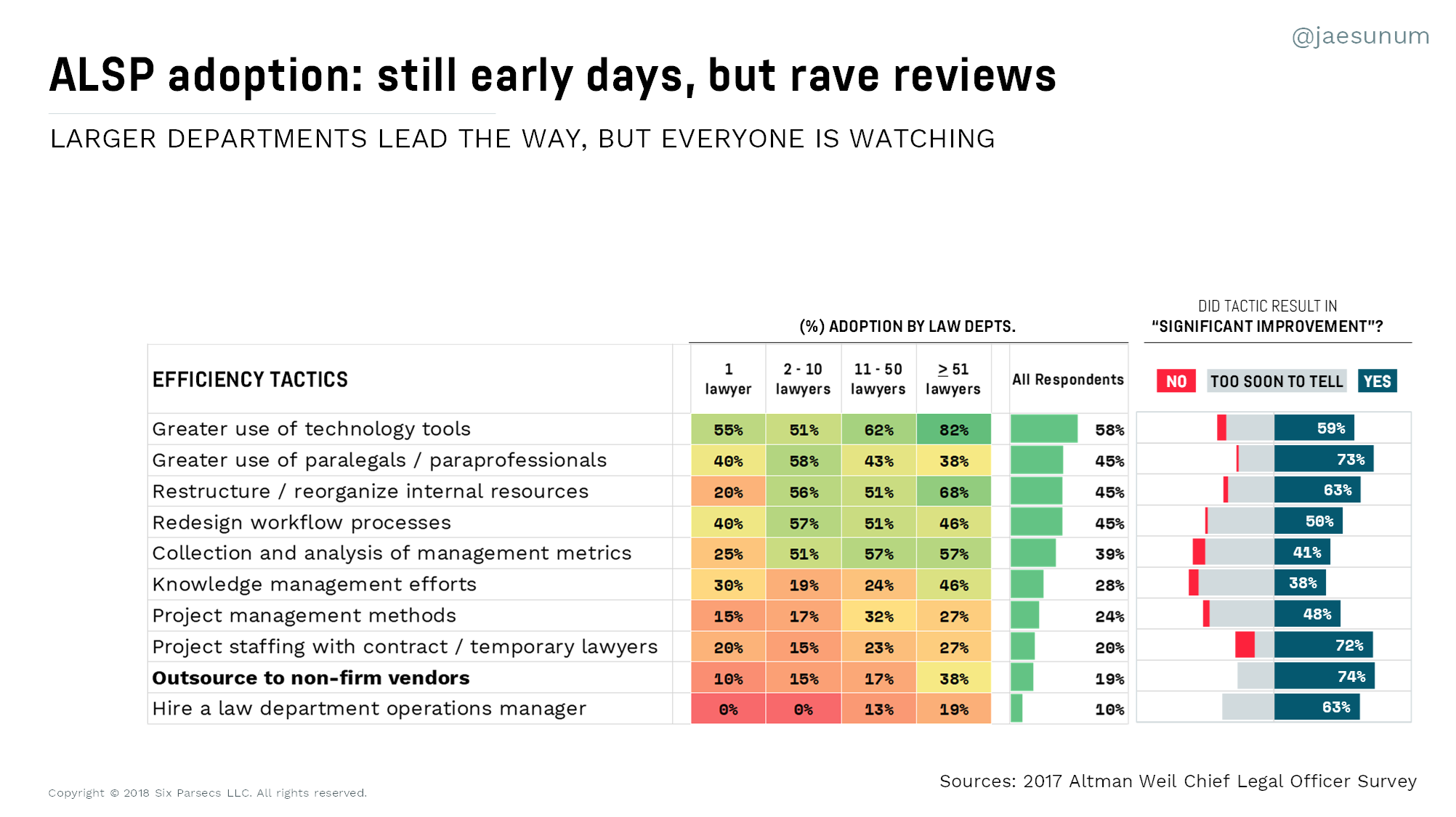

Less spectacularly but more quantitatively convincing are the early signals in market data. In Altman Weil's most recent survey of Chief Legal Officers, ALSP adoption still appears nascent, with only 19% of law departments outsourcing to ALSPs to drive efficiency. However, adoption by large departments is much higher at 38%. Most deserving of note is that non-firm vendor use was rated the most effective tactic in driving efficiency, with 74% of Chief Legal Officers indicating a significant improvement from working with non-firm vendors.

Thomson Reuters Legal Executive Institute, in partnership with the Georgetown University Law Center, released a 2017 study showing that ALSPs were on a rapid growth trajectory and had already eclipsed $8.4 billion in annual revenue. Indeed, because of the displacement effect—ALSP labor substantially less expensive than either outside or inside counsel—the $8.4 billion understates the amount of workshare ALSPs have captured. While the bulk of ALSP work was still in traditional areas like first-pass document review, the study identified the “increasing sophistication of ALSPs” and foresaw “ALSPs playing a greater role in increasingly complex services and tasks.”

We are already seeing this play out at the top ALSPs in the market. Just last month, Axiom Law shared its expected financial results for 2018, reporting revenues of nearly £50 million in the UK and $360 million globally. For context, Axiom's current worldwide revenues would place the ALSP at 97th in the 2018 Am Law 100 and about $60 million shy of the Global 100.

Citing new models that have emerged since the early days of legal process outsourcers, Radiant Law's Hamilton believes “clients have never had so many options, with suppliers such as Radiant Law able to offer highly sophisticated support with business models that encourage the use of technology and process improvements combined with senior judgement calls.”

Indeed, as the senior counsel of a major global financial institution, who uses QuisLex for several large scale derivative documentation reviews, puts it, “… what makes it so impressive is that we are dealing with very sophisticated netting and prime brokerage agreements that require very nuanced legal analysis … when interpretation questions come up our feedback is immediately incorporated into the process … we never see the same issue again.”

Bayley of Novus Law summarizes it best: “Once our corporate clients experience working with us – and the breadth and depth of our team – they quickly realize that we can help them with increasingly sophisticated and complex services to solve business problems.”

ALSPs, once considered a remote threat on the horizon, are already here. They're taking a sizable bite out of Big Law's market share and they have their sights set ever upward.

Incumbents should take note.

Casey Flaherty is the founder of Procertas. He is a former inside and outside counsel who now consults with law departments and law firms on legal operations (Full disclosure: Casey works with many of the organizations mentioned in this piece).

Jae Um is founder and executive director of Six Parsecs. She is an ALM Intelligence Fellow.

More information on the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program can be found here

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trending Stories

- 1Silk Road Founder Ross Ulbricht Has New York Sentence Pardoned by Trump

- 2Settlement Allows Spouses of U.S. Citizens to Reopen Removal Proceedings

- 3CFPB Resolves Flurry of Enforcement Actions in Biden's Final Week

- 4Judge Orders SoCal Edison to Preserve Evidence Relating to Los Angeles Wildfires

- 5Legal Community Luminaries Honored at New York State Bar Association’s Annual Meeting

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250