Law Firms Are More Profitable Than Ever. How are They Doing It?

Given the obstacles law firms are facing, profitability shouldn't be increasing. A look at how firms are doing it.

October 03, 2018 at 09:01 AM

11 minute read

Law firm profitability is at a record high. The average equity partner, at an Am Law 200 firm, received $1.8 million in profit sharing compensation last year. This is higher than any point in recorded history (the Am Law 200 data goes back to 1984). Average profits per equity partner are nearly $500k dollars more, in nominal terms, than they were at the peak in profitability experienced before the past downturn. Even after adjusting for inflation, profits per equity partner are $125k per year more than they were a decade ago. Not bad if you ask me.

Given the myriad of obstacles law firms are facing, such increases in profitability seem striking. If clients are becoming more discerning buyers, profitability should be coming under pressure. Rising competition from alternative service providers and the ever-forward march of technology adoption should be having a similar, negative, effect on profitability. This raises an obvious question – how are law firms doing it?

But Wait, Are Law Firms Really Doing that Well?

Before jumping into the question of how law firms are increasing profits per equity partner, it's worth looking more closely at the numbers. Looking at average PPEP, while useful, can be misleading. Averages, after all, are prone to distortion. It's possible, for example, that a few firms are driving the average increase in profitability and the vast majority of firms are struggling. So, let's dig a bit deeper.

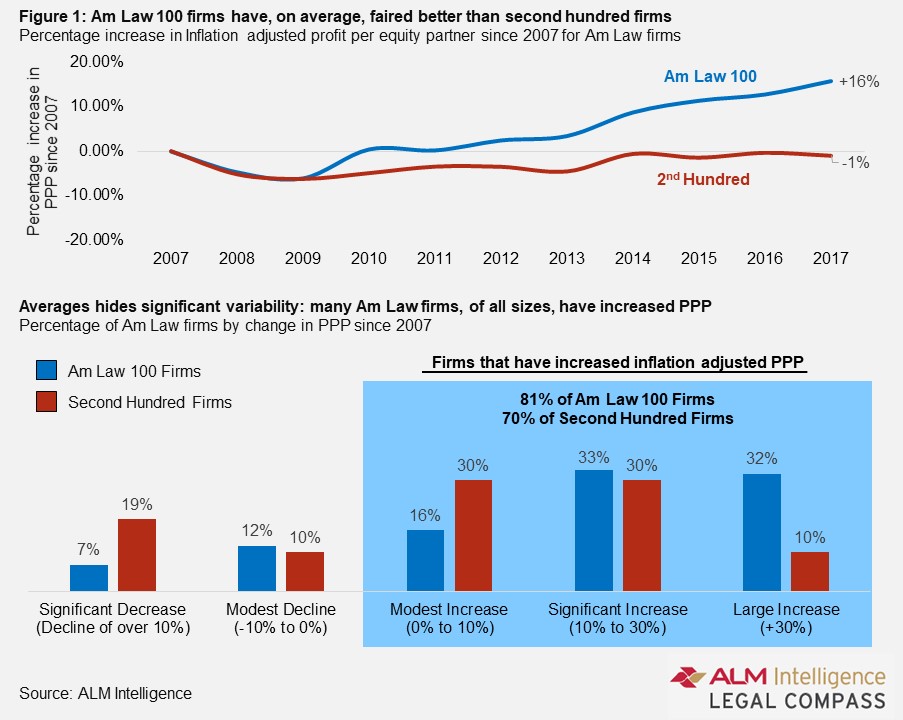

Figure 1 shows two graphs. The first looks at the average change, since 2007, in PPEP for the Am Law 100 and Second Hundred. This data suggests a wide divergence in performance between larger Am Law 100 firms and their smaller, second hundred brethren. On average, Am Law 100 firms have seen a 16% increase in inflation-adjusted PPEP while Second Hundred firms have seen a slight, 1%, decline.

The second graph in Figure 1 digs even deeper, looking at the performance of individual firms. Two trends emerge above the others. First, second hundred firms have, on average, fared slightly worse than their larger peers. More second hundred firms have reported significant declines in PPEP. Also, fewer second hundred firms have reported large increase in PPEP. While this trend is important, it is overshadowed by an even larger trend – wide variability in performance. Smaller firms are not, uniformly, performing poorly. In fact, many smaller firms have outperformed their larger peers by a wide margin over the past decade.

The overwhelming take way from this data is that while large firms have fared slightly better, the vast majority of firms within the Am Law 200 have reported increases in inflation adjusted PPEP over the past decade. The next question is – how are they doing it?

The Levers Firms Can Use to Increase Profitability

There are many ways for a law firms to increase profitably. There are even more ways to analyze the issue. Looking at profitably at a matter level would, for example, lead us to focus on issues like pricing strategies, the number of hours each task takes, and the average cost of various time keepers. Such an analysis would be fascinating. The problem is that there is not a lot of public data at the engagement level available for analysis. Where there is good data, however, is at the firm level, which will be the focus for this brief.

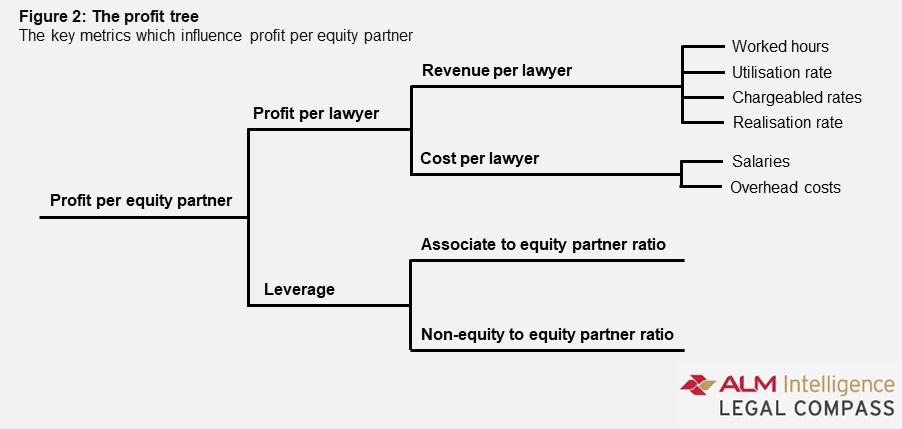

Broadly speaking there are four ways to increase firm wide profitability. The most straightforward path is to focus on increasing revenue per lawyer. This can be achieved in several ways. Firms can increase worked hours by, for example, increasing hourly targets on associates. They can also increase utilization rates or realization rates. While these “levers” can boost a firm's revenue per lawyer the most potent lever is rate increases. Increasing prices – which most often means increasing hourly rates – is the most rapid and straightforward path to increasing revenue per lawyer.

The next, most obvious, path to higher PPEP is to reduce costs. Again, there are multiple ways to accomplish this goal. Firms, can reduce salary costs. This could be accomplished by cutting salaries or, more realistically, by shifting work to lower cost resources – either less skilled individuals or individuals who are based in lower cost locations. While these strategies have been pursued by some firms, the more common route to lower costs has been to reduce both direct and indirect expenses, or more broadly speaking, “overhead”.

The last two paths to boost a firm's profits per equity partner are to increase the firms' leverage by either hiring more associates or by shifting the structure of the partnership to include more non-equity partners and fewer equity partners.

The Levers Firms Are Relying on Most

To analyze which levers law firms have used to increase profitability, I employed a tool more often used by economists than law firm managers. The concept of “elasticity” in economics is typically used to help economists understand how changes in demand impact prices. Specifically, economists will usually look at how a 1% increase in demand for a product impacts price. The same principle can be used for the levers of profitability. What impact does a 1% increase in revenue per lawyer have on a firm's profit per equity partner? What impact does a 1% increase in associate leverage have? Using this method, we can identify the impact each lever has had on the firm's PPEP over the past decade and isolate those levers that have had the largest impact (Note: A special thanks to Hugh Simons for helping devise this solution).

So, what does the data say? Broadly speaking, increases in revenue per lawyer have had the strongest impact for most firms (see Figure 3). Revenue per lawyer has been the primary driver of PPEP increases for over a third of the Am Law 200. Increases in associate leverage comes in second, with nearly a quarter of firms reporting that lever as their primary driver of PPEP increases. Decreases in cost per lawyer comes in third – with 18% of firms reporting this as their primary driver of PPEP increases.

Conspicuously low on this list is reductions in the number of equity partners. Much attention has been paid to de-equitizations over the past several years. Many legal market watchers argue that firms are “gaming” their PPEP numbers by de-equitizing partners. Putting aside the validity of the “gaming argument (this analyst does not believe de-equitizing partners is “gaming”) the data in Figure 3 suggests de-equitization has played only a small role. Just 14% of firms report decreases in the number of equity partners as a primary driver of PPEP increases. Another 11% report that increases in non-equity partners are their primary driver of PPEP increases. If these firms were turning equity partners into non-equity partners, this could be the flip slide of the same coin. In most cases, this is not what is happening. Most of the firms in this group have been growing their non-equity partnership faster than their equity partnership. This is not the same thing as de-equitization.

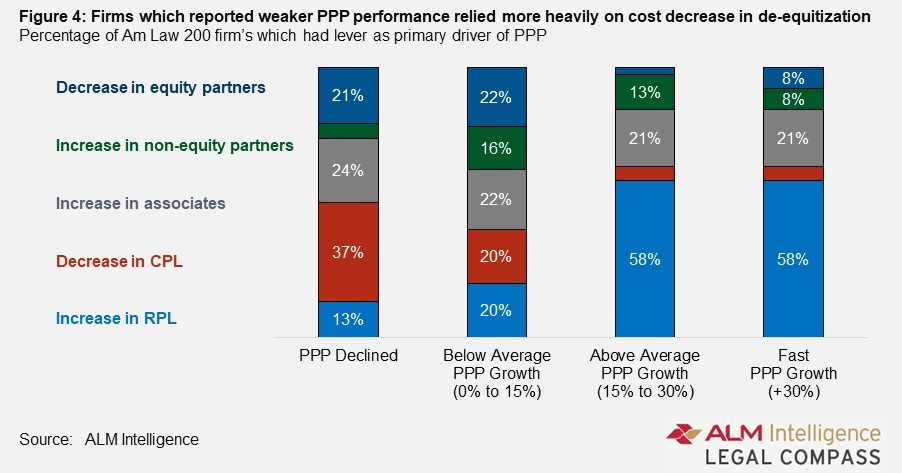

Different Strategies For Different Firms

Digging a bit deeper into this data reveals an interesting trend. If we group the Am Law 200 by PPEP performance over the past decade into groups of firms that declined in PPEP, those that grew slowly, and those that grew quickly, a clear trend emerges (see Figure 3). Firms which saw declines in inflation adjusted PPEP since 2007 have relied more heavily on cost reductions and de-equitizations to boost their PPEP. This stands in stark contrast to the firms which have seen fast inflation adjusted PPEP growth. These firms have relied heavily on increase in revenue per lawyer (most probably due to rate increases) to boost PPEP.

What could explain why these firms have such differing strategies to boosting PPEP? Two possibilities exist. The first is different firms have pursued differing strategies out of choice and only one strategy – focusing on revenue per lawyer – has succeeded. The more likely possibility is that some firms did not have the luxury of increasing rates and others did.

The firms which have had PPEP declines tend to have significantly lower revenue per lawyer than those which have had above average or fast PPEP growth. The lower revenue-per-lawyer numbers from these firms suggest they focus on mid-value, as opposed to high-value, work. Anecdotal evidence tells us mid-value work has come under intense rate pressure over the past several years. This has left these firms with fewer options to increases PPEP. Instead of raising rates, these firms have had to focus on process improvements, cost cutting, leverage increases and de-equalization to boost profitability.

Are these strategies sustainable?

It is interesting to question which of these strategies is most sustainable. Some are clearly not. De-equitizations, for example, are a single use tactic – once the partnership is “right sized” little more can be done. Cost cutting focused on overhead appears similarly limited. Overhead costs can only be reduced so much. There is a natural limit on the number of support staff a law firm can let go or its ability to reduce square footage per employee. Firms that have relied heavily on these tactics may be in trouble. While additional tweaks to partnership structures and overhead expenses may be possible, the low hanging fruit in these areas appears to have been picked.

One possibility for these firms is to expand their cost cutting efforts beyond overhead expenses. The most obvious place to look for additional cost savings is in salary costs associated with the delivery of legal services. These costs typically account for 70% – 80% of a law firm's total costs. Small reductions, therefore, could result in significant savings. Firms could reduce the cost of delivering legal services by leveraging technology, streamlining processes, or by shifting work to lower costs locations. Some firms are putting significant effort into these areas. For example, take a look at the shared service center trend among large law firms – Baker Mckenzie's Belfast office is a particularly good example. Another place to look is the trend toward productizing legal services – Littler Mendelson's CaseSmart program is a stellar example. These programs have been proven to be tremendously successful at reducing costs and improving profitability. They represent the tip of the iceberg on what can be done in these areas.

The million-dollar (or perhaps billion-dollar) question is if increasing rates on clients is sustainable. Many firms have clearly been relying on this tactic to boost profitability. So far, this strategy has yielded results. Will clients, at some point, say “enough is enough”? In lower and medium value areas of work the answer is – almost certainly. But what about higher value work? In these areas it is difficult to say when or if client pressure will come to bear. Clients have fewer options for complex, high value legal advice. This gives firms significant market power to demand – and get – higher rates.

Are firms that focus on higher value work safe? No. The big worry for these firms is that technology and process improvements will transform legal advice that was previously complex and high value into routine mid-value work. This has already happened in some areas. Legal advice which has undergone this transition has come under rate pressure. If more work follows this route firms that focus on higher value work will find themselves in a tricky situation. They could alter their model, cut costs and reform their partnerships as mid-market firms have already done. Alternatively, they could retreat from some areas of work and focus on services where they can continue to demand the highest prices. Such a strategy may require ceding market share to mid-market rivals. This would leave these firms smaller but more profitable. The choice between these two options – changing your model or getting smaller – will be gut wrenching for many firms. They can take solace in the fact that most of the legal market had to make these choices a decade before them.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trending Stories

- 1How ‘Bilateral Tapping’ Can Help with Stress and Anxiety

- 2How Law Firms Can Make Business Services a Performance Champion

- 3'Digital Mindset': Hogan Lovells' New Global Managing Partner for Digitalization

- 4Silk Road Founder Ross Ulbricht Has New York Sentence Pardoned by Trump

- 5Settlement Allows Spouses of U.S. Citizens to Reopen Removal Proceedings

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250