President Donald Trump. Photo: Bloomberg

President Donald Trump. Photo: BloombergEven as President, Trump May Face Civil Suit in NY Courts, Law Professors Aim to Argue

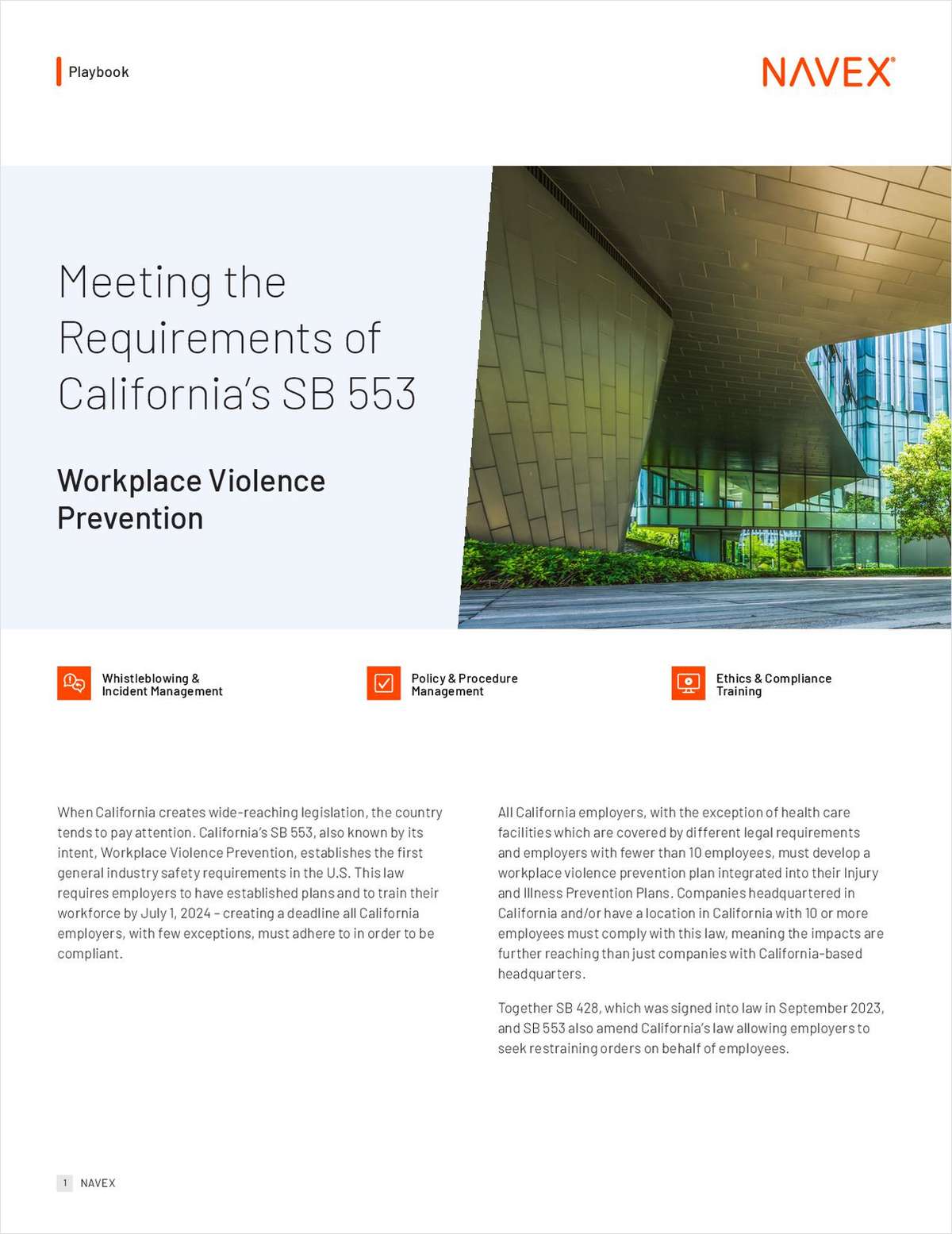

A group of law professors who argued two decades ago that former President Bill Clinton should not be immune to a civil lawsuit in federal court are now asking to make the same argument against President Donald Trump in New York Attorney General Barbara Underwood's lawsuit against the Trump Foundation.

October 09, 2018 at 04:33 PM

7 minute read

The original version of this story was published on New York Law Journal

President Donald Trump should not be exempt from facing civil litigation during his time in the White House, say a group of law professors seeking to be heard in the New York attorney general's suit over alleged illegality in the Trump Foundation.

The argument was posed in a proposed brief sent to Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Saliann Scarpulla. The professors signing on to the document argued two decades ago in the U.S. Supreme Court case Clinton v. Jones, which opened the door to a sexual harassment case against President Bill Clinton in federal court.

Their argument in the Trump Foundation case, which was brought by New York Attorney General Barbara Underwood, echo the reasoning in Clinton.

The main point they seek to make is that no law exempts Trump from being sued in state court. Trump's attorneys have argued that their client, as president, ought not to be haled into civil litigation.

“Congress has not immunized sitting presidents from civil suits, though it clearly could do so,” the proposed brief said. “And despite [Trump]'s arguments to the contrary, neither the Constitution's supremacy clause nor any other constitutional principle prevents state courts from adjudicating claims brought against sitting presidents when those claims implicate only the respondent's unofficial acts and capacities.”

The professors are Stephen Burbank from the University of Pennsylvania Law School, Richard Parker from Harvard Law School and Lucas Powe Jr. from the University of Texas Law School.

They were recruited by Richard Primus, a constitutional law professor at the University of Michigan Law School. Aditi Juneja and Ian Bassin, both from Protect Democracy in Manhattan, are listed alongside Primus as attorneys for the professors.

“I'm concerned that the Trump administration poses a severe threat to our constitutional order and to the rule of law as we have known it,” Primus said on Tuesday. “We Americans take the rule of law mostly for granted, but we shouldn't. It's a fragile thing. President Trump has little respect for law, and our norms that say law must be taken seriously are eroding while he is in office.”

Underwood's lawsuit alleged that Trump used his charitable foundation for political purposes and to settle a series of personal financial obligations before he took office last year.

Burbank said when reached by phone on Tuesday that some professors involved in Clinton in the 1990s may have been driven by partisan interests against Clinton at the time, but that he was not. He said he welcomed the opportunity to make the same argument in a very different case more than 20 years later.

“When the opportunity arose to reaffirm the position in litigation involving the president of the other party, I was delighted,” Burbank said.

Powe echoed that thought on Oct. 4, saying his position has not changed since Clinton.

“I thought it would be hypocritical to do one and not do the other,” Powe said. Parker did not immediately return a request for comment.

They are three of several academics who wrote to the U.S. Supreme Court when Paula Jones, a former state employee in Arkansas, sued Clinton over sexual harassment allegations from when he was the governor of Arkansas. Clinton's attorneys had argued that he was immune from litigation as a sitting president.

The professors wrote otherwise to the high court, which determined that Clinton could be sued in federal court based on events that happened before he took office.

“[W]e have never suggested that the president, or any other official, has an immunity that extends beyond the scope of any action taken in an official capacity,” the Supreme Court wrote in Clinton.

Alan Futerfas, a Manhattan attorney representing Trump and the foundation, argued in a motion to dismiss the lawsuit in August that while the Supreme Court allowed the federal lawsuit to proceed in Clinton, it cautioned the same jurisdiction within state courts. The supremacy clause of the U.S. Constitution exempts Trump from such a lawsuit, he said.

“The same principles that prohibit state courts from asserting jurisdiction over the official conduct of federal officials prohibit a state court from exercising any authority over a sitting president, who embodies the office, such that any assertion of jurisdiction by a state court over the president will inevitably interfere with, or burden, his or her ability to exercise the president's Article II powers,” Futerfas wrote.

The professors conceded in their proposed brief that the Supreme Court did not resolve whether a sitting president may claim immunity from state litigation in Clinton.

But that shouldn't matter in this case, they argued, because the lawsuit does not involve Trump's official acts as president. The supremacy clause would only apply if a state court tried to have 'direct control' over the president's official actions, they said.

“A state court exercising such 'direct control' might issue an order that would block a president from executing his office, and that would indeed raise a problem under the supremacy clause,” the proposed brief said. “But no such problem arises in a suit like this that has nothing to do with the president's official role and in which no judicial order would interfere with the president's execution of any federal function.”

Primus was among a group of professors who made the same argument in a different case against Trump last year. That case involves a former contest on “The Apprentice” who is suing Trump for defamation after he said publicly that she lied about his behavior toward her. She claimed Trump kissed and groped her without her consent on more than one occasion.

Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Jennifer Schecter decided earlier this year that Trump was not immune from that lawsuit, though Trump's attorneys in the case are appealing that decision.

The issue of presidential immunity may become more relevant in the coming months. Officials with New York state and New York City are reviewing claims that Trump and his family may have committed tax fraud in the 1990s, which were reported by The New York Times last week.

The next appearance in the Trump Foundation lawsuit is scheduled for later this month, when the parties will argue on Underwood's petition, which seeks restitution from the foundation of $2.8 million and to bar Trump from serving as the director of a nonprofit in New York for a decade.

READ MORE:

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Google Fails to Secure Long-Term Stay of Order Requiring It to Open App Store to Rivals

Orrick Secures Summary Judgment for RingCentral in Privacy Class Action

NY Lateral Partner Moves Spike, Especially in PE and Funds Practices

'That's Not the Job' for the DOL: Crop of Suits Against Biden Administration

6 minute readTrending Stories

- 1The Law Firm Disrupted: Playing the Talent Game to Win

- 2A&O Shearman Adopts 3-Level Lockstep Pay Model Amid Shift to All-Equity Partnership

- 3Preparing Your Law Firm for 2025: Smart Ways to Embrace AI & Other Technologies

- 4BD Settles Thousands of Bard Hernia Mesh Lawsuits

- 5A RICO Surge Is Underway: Here's How the Allstate Push Might Play Out

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250