Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 (MH370/MAS370) was a scheduled international passenger flight that disappeared on March 8, 2014, while flying from Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Malaysia, to Beijing Capital International Airport in China.

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 (MH370/MAS370) was a scheduled international passenger flight that disappeared on March 8, 2014, while flying from Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Malaysia, to Beijing Capital International Airport in China.Federal Judge Dismisses US Lawsuits Filed Over Malaysia Airlines Disappearance

Family members of 88 passengers who sued in U.S. courts will have to refile cases in Malaysia courts after a federal judge dismissed all 40 lawsuits.

December 12, 2018 at 05:16 PM

5 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

Family members of 88 passengers who sued in U.S. courts over the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 in 2014 will have to refile cases in Malaysia courts after a federal judge dismissed all 40 lawsuits.

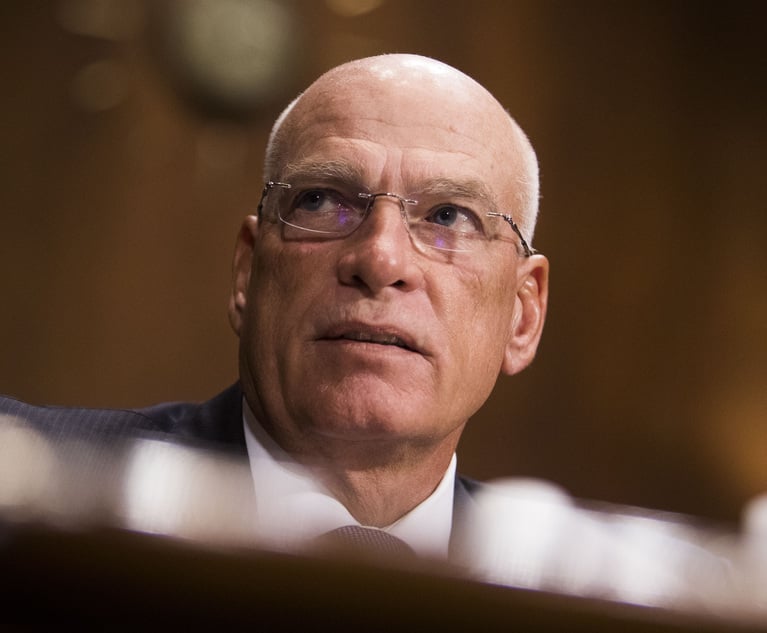

In “one of the greatest aviation mysteries of modern times,” U.S. District Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson in Washington, D.C., found that “the claims asserted in the consolidated complaints have a substantial and overriding nexus to Malaysia that outweighs the less substantial connection to the United States.”

Brown wrote that the dearth of U.S. citizens as passengers or plaintiffs, and the failure to identify the cause of the aircraft's disappearance, prompted her to dismiss the cases under the doctrine of forum non conveniens. Malaysia Airlines and Boeing had filed a joint motion to dismiss the cases based on the theory that a U.S. court was an inconvenient forum.

“The substantial connections that exist between the country of Malaysia and the tragic incident that precipitated the legal actions that compromise the instant MDL are undeniable,” wrote Jackson in her Nov. 21 ruling, which came nearly one year after she heard oral arguments in the multidistrict litigation.

The judge found all other dismissal motions, including one brought under the U.S. Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, to be moot in light of her decision.

Lead plaintiffs attorneys Mary Schiavo of Motley Rice in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, and Steven Marks of Podhurst Orseck in Miami, who pursued different legal theories in the cases, did not respond to requests for comment.

Requests for comment also went unanswered from Malaysia Airlines attorney Richard Walker, a member of Chicago's Kaplan, Massamillo & Andrews, and Mack Shultz of Seattle's Perkins Coie, who represented Boeing.

The flight, with 239 passengers and crew members, took off from Kuala Lampur, Malaysia, on March 8, 2014, headed to Beijing, China. Minutes later, the plane made an abrupt turnaround, flying seven hours into the Indian Ocean.

Some parts of the plane washed ashore, but not the cockpit voice recorder or flight data recorder. Despite two exhaustive searches, the wreckage site remains unknown.

Most of the 227 passengers were from China. Under the Montreal Convention, which is an international treaty from 1999, passengers from foreign countries can't sue a foreign airline in U.S. courts, which offer significantly higher damage awards.

Yet six of the lawsuits brought claims under the Montreal Convention against Malaysian Airlines, while 35 named U.S.-based Boeing, mostly for wrongful death and products liability claims, because it manufactured the 777 aircraft, the model of the plane that disappeared.

In the Montreal Convention claims, plaintiffs attorneys focused on the fact that three of the passengers were U.S. citizens, while one had lawful permanent residence in the United States. They also noted that a law allowing Malaysia Airlines to restructure following Flight 370's disappearance could limit the airline's liability.

Yet the idea that she would have to assess the validity of that law was “potentially troubling,” Jackson wrote.

“Questions regarding the validity of foreign laws that are effective in foreign countries are better left to courts in those countries,” she wrote.

As to the liability matter, she wrote that “it is well established that the availability and the adequacy of a forum does not turn on whether exactly the same remedy that exists in the United States is available in the foreign forum.”

The plaintiffs' strongest argument, Jackson wrote, was for the three passengers who were U.S. citizens, in particular, Philip Wood, who was working for IBM in Malaysia at the time he died. But even those U.S. connections didn't suffice, she wrote, since none of those passengers was living in the United States.

Jackson cited a 2010 ruling by U.S. District Judge Charles Breyer in the Northern District of California that sent cases brought over Air France 447 to France. In that case, just two Americans living abroad were among the 228 passengers and crew members who died when the aircraft crashed in the Atlantic Ocean in 2009.

“So it is here,” Jackson wrote. “It is Malaysia's strong interest in the events that give rise to the claims at issue here that makes this a distinctly Malaysian tragedy, notwithstanding the presence of the few Americans onboard Flight MH370.”

As to the claims against Boeing, the judge noted that the aircraft manufacturer had agreed to submit to personal jurisdiction in lawsuits filed in Malaysian courts as part of its dismissal motion, and toll the statute of limitations for 120 days. In a separate order, Jackson required Boeing to allow plaintiffs until March 21 to refile their claims in Malaysia. There already are 27 cases pending in the High Court of Malaya at Kuala Lumpur, according to Jackson's ruling, but none against Boeing.

She also acknowledged the investigative findings relating to Flight 370's disappearance. Boeing had cited a July 30 report by a Malaysia-based international group of government investigators in support of its motion to dismiss.

The report pointed to “the possibility of intervention by a third party,” such as air traffic controllers, and found no evidence of “a mechanical malfunction with the aircraft's airframe, control systems, fuel or engines.”

The lack of a specific design or manufacturing defect tied to Flight 370, Jackson wrote, made her “hard pressed to find that the interests of the United States in resolving the instant product-defect claims against Boeing outweigh what is, at its core, a Malaysian tragedy.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Unlawful Release'?: Judge Grants Preliminary Injunction in NASCAR Antitrust Lawsuit

3 minute read

Justice on the Move: The Impact of 'Bristol-Myers Squibb' on FLSA Forum-Shopping

9 minute read

Federal Judge Grants FTC Motion Blocking Proposed Kroger-Albertsons Merger

3 minute read

Frozen-Potato Producers Face Profiteering Allegations in Surge of Antitrust Class Actions

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Call for Nominations: Elite Trial Lawyers 2025

- 2Senate Judiciary Dems Release Report on Supreme Court Ethics

- 3Senate Confirms Last 2 of Biden's California Judicial Nominees

- 4Morrison & Foerster Doles Out Year-End and Special Bonuses, Raises Base Compensation for Associates

- 5Tom Girardi to Surrender to Federal Authorities on Jan. 7

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250