Getting Partner Profitability Right

Many firms take approaches that undervalue leverage; it's time to fix them.

December 18, 2018 at 08:43 AM

7 minute read

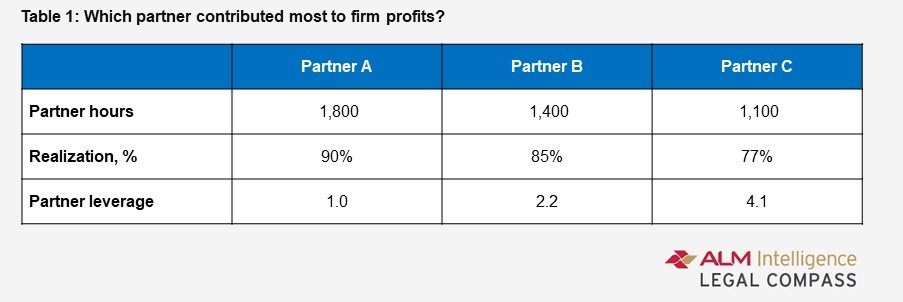

Consider three partners with the 2018 performance metrics shown in Table 1. Which one contributed most to firm profit? Partner A is a tax partner who worked hard serving clients willing to pay for the time billed; Partner B is a deal lawyer whose major client did no major deals last year; and Partner C is a junior litigator who discounted heavily to win a big case that then settled early.

Partner compensation committees throughout Big Law will grapple with this kind of question in the coming weeks. Many will incline to believe that Partner A (who kept busy on high realization work) contributed robustly to firm profits, while Partner B (who struggled to get busy and had average realization) contributed a little, and Partner C (with soft hours and very low realization) probably didn't contribute anything at all.

It would surprise many compensation committees to know that all three partners made equal contributions to the firm's profit pool. How can this be? Simply put: partners' intuitive sense of profitability overemphasizes the value of hours and realization, and undervalues leverage. This is particularly a problem at firms with wide ranges in partners' practices on these metrics.

This profitability outcome rests on a basic principle: in determining partner profitability one should include only those factors that the partner controls. In MBA courses, this is referred to as “aligning accountability with responsibility”. This is critical for partners to have faith in the metric; if you do otherwise then partners simply get frustrated and disregard the result, thereby undermining the reason to measure profitability in the first place, namely to guide partners on how to improve it. This is an important principle too for comp committees who should be focused as cleanly as possible on the effects on profitability of decisions and actions taken by a particular partner, and should be blocking out the noise of decisions taken by administrators.

There are only three profitability drivers that partners control:

- Revenues realized from a client for a particular matter,

- Time of lawyers of different seniorities deployed in delivering on the matter, and (to degrees that vary by firm),

- How busy the relevant lawyers are kept. Partners do not control overhead expenses, e.g. rent, administrative staff compensation, IT, recruiting costs.

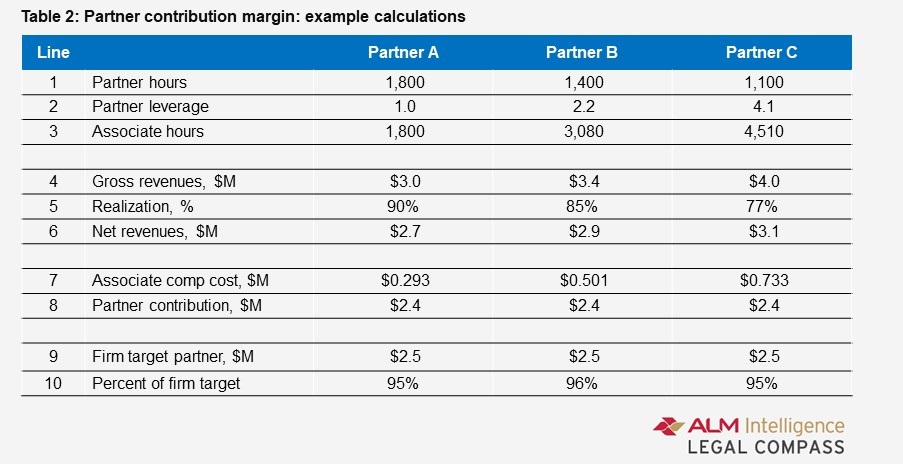

Table 2 lays out how this principle applies to the three partner profiles above. It starts with partner hours (line 1) and leverage (line 2); together these define associate hours (line 3). Multiplying these hours by 'rate card' billing rates (assumed in this example to average $1,000/hour and $650/hour for partners and associates, respectively) yields the gross revenues (line 4).

Most firms have reasonably robust ways of assigning revenues by partner. That said, it's not always without issues. The sharing of revenues between partners who source and execute (i.e. 'finders' and 'minders') can be controversial. I've seen firms leave this to negotiation between individual partners while others lay out guidelines (e.g. origination receives a robust percentage initially and then declines over time) and yet others augment the revenues to be credited if partners team to generate them. One thing I'd discourage is giving credit in perpetuity for beginning a client relationship; it dissuades partners with the necessary skills for this critical activity from continuing to establish new relationships. There's no perfect assignment methodology but, as with all else in management, something generally correct is better than nothing at all.

The next step is to apply a realization rate (line 5) to these gross revenues to get to net revenues or cash receipts (line 6). There is typically a timing challenge with this as cash receipts lag the recording of hours by two to three months. Most firms find using a 12-month trailing average to be an effective work around.

Following the principle above, we subtract only the compensation cost associated with the lawyer time that generated these revenues (line 7) to arrive at partner contribution (line 8). In traditional accounting, these compensation costs are referred to as 'direct costs' (as they directly relate to the revenues) and partner contribution is referred to as 'contribution margin' (as this is the amount these revenues 'contribute' to coverage of the firm's overhead costs and thereafter to creation of the firm's profit pool).

The lawyer time encompasses all lawyers (or other timekeepers) except for equity partners. The lawyer cost is determined as the sum for all lawyers involved of their billed hours times their annual compensation cost (base and bonus) converted to an equivalent cost per hour. For partners who staff their matters from a dedicated pool of lawyers, the cost-per-hour should be based on the individual lawyer's billing history; this is because in these circumstance partners have control over the lawyer's hours and hence their hourly cost. For partners who can exert no such control (e.g. where staffing is done from a large pool) then a standard cost-per-hour by lawyer cohort (e.g. associate year) should be used. In the example calculations, this is approximated consistently as $162.50.

This approach diverges from those in use today in two areas. First, it's common to subtract an allocation of overhead (in addition to lawyer compensation) to get to partner profitability. Firms are drawn to doing this so they have a full accounting of all their costs. I'd propose that rather than allocate overhead, which always begets a battle, firms instead compare the partner profitability amount (i.e. the number arrived at after subtracting only the compensation costs) with a target amount that covers overhead and provides for the desired profit pool. This can be determined as revenues, less lawyer comp, per partner from the firm's financial plan for the year. This target amount is assumed in this example to be $2.5 million (line 9); each partner's margin is then translated to a percentage of this target (line 10). Partners who are contributing more than the firm average target will have percentages greater than 100 percent.

The second divergence is that many firms include as a 'cost' the compensation of equity partners. They do this to capture any disconnects between the economics of a partner's practice and their compensation. This is problematic primarily because partner compensation is profit, not cost. It's tricky too because it muddles together two very distinct things: how much a partner contributes to the profit pool through their actions and how much they are allocated from the profit pool as decided upon by the compensation committee. A better way to get at how well the economics of a partner's practice aligns with their compensation is to compare two numbers: each partner's contribution margin as a percent of the sum of contribution margin for all partners, and each partner's compensation as a percent of the total partner compensation. If the former exceeds the latter, the partner is being undercompensated relative to their practice's economic contribution, (fuller discussion here).

Closing thought

Of course, all that said, partner comp is about way more than economics. Long term firm building is hugely important, as is getting along with other partners and being perceived as being a good partner. But it's an important element—long, or sustained, variations are unfair and spell trouble. It's worth the relatively small of effort to get it right.

Hugh A. Simons, Ph.D., is formerly a senior partner and executive committee member at The Boston Consulting Group and chief operating officer at Ropes & Gray. He writes about law firms as part of the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program. He welcomes readers' reactions at [email protected]

More information on the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program can be found here.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

After Breakaway From FisherBroyles, Pierson Ferdinand Bills $75M in First Year

5 minute read

Big Law Practice Leaders Gearing Up for State AG Litigation Under Trump

4 minute read

KPMG Wants to Provide Legal Services in the US. Now All Eyes Are on Their Big Four Peers

Trending Stories

- 1New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 2No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 3Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 4Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 5Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250