Wanted ASAP: Pioneering Women Law Profs for Oral History Project

With interviews completed of more than 40 women law professors who entered the legal academy in the 1960s and after, the Women in Legal Education Oral History Project is seeking additional subjects in order to capture the voices of the first true generation of women professors.

January 16, 2019 at 03:00 PM

6 minute read

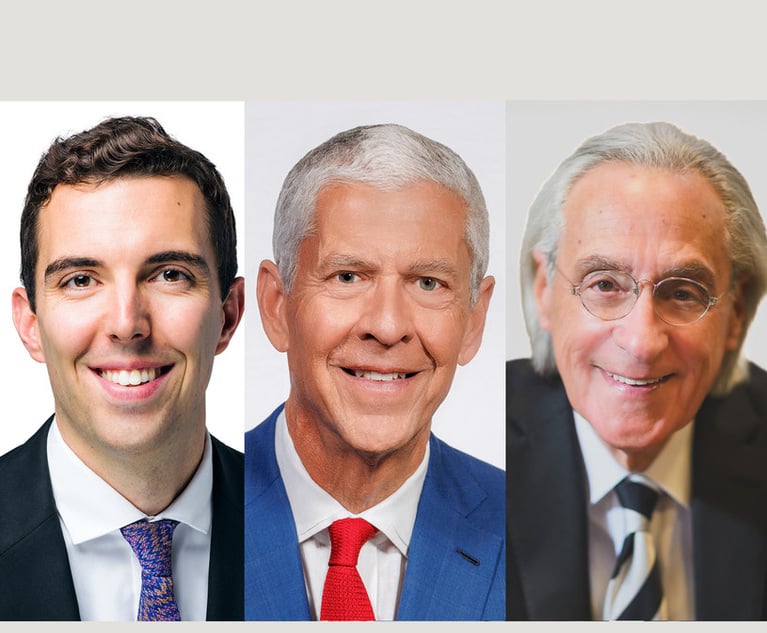

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is interviewed by Marina Angel, professor at Temple University Beasley School of Law, for the Women in Legal Education Oral History Project.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is interviewed by Marina Angel, professor at Temple University Beasley School of Law, for the Women in Legal Education Oral History Project.

When Herma Hill Kay made the faculty interview rounds at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law in 1960, the school was looking to replace its sole female faculty member and the first woman to be tenured at a major law school, Barbara Nachtrieb Armstrong. Berkeley wanted another woman.

Kay aimed to look her best on that warm spring day, pulling on white gloves and donning a suit and beige cloche-style hat that swept low over her face. She interviewed with professor after professor, all male. Meanwhile, the phone in Armstrong's office kept ringing throughout the day. Armstrong eventually revealed the problem.

Herma Hill Kay.

Herma Hill Kay.“You're going to have to take your hat off,” Kay would recall Armstrong saying, more than five decades later. “The men want to see what you look like.”

For Kay, abandoning the hat was a nonstarter, given her hair's lack of cooperation with the weather that day.

“Barbara gave me a stare and said, 'All right, but when you come for your second day of interviews, can you wear a smaller hat?'” Kay recounted. “I said, 'Sure, but I didn't know there was a second day of interviews.' Barbara said, 'There will be now.'”

Kay's story, which underscores how the first generation of women legal professors had to struggle to be taken seriously and establish a foothold within the male-dominated academy, is captured in a video interview she conducted with the Women in Legal Education Oral History Project several years ago. Kay, who served as dean of Berkeley Law from 1992 to 2000 and became one of the biggest names in the academy, died in 2017.

The project seeks to collect the stories and wisdom of the academy's female pioneers and preserve those insights for current and future law teachers. Despite Kay's impressive credentials, which included graduating third in her class at the University of Chicago Law School and clerking for a California Supreme Court justice, her appearance was still of utmost concern to Berkeley's decision makers at the time.

“History helps those who come after more quickly recognize the challenges in our path,” said Mitchell Hamline School of Law Professor and project coordinator Marie Failinger in remarks at the Association of American Law Schools annual meeting earlier this month, where a panel of women professors discussed the oral histories and their own professional barriers. “To not know the history of the women who came before us diminishes our own power.”

The oral history project has been around since 2014, and it gained momentum three years ago when the AALS agreed to host it. Project leaders are on the hunt for interview subjects and volunteers to conduct and record those interviews.

The project has collected about 40 interviews thus far. They include U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who taught at Rutgers Law School from 1963 to 1972 after being rejected from other legal jobs despite graduating first in her class at Columbia Law School. Stanford Law School professor Deborah Rhode; retired University of Michigan law professor Margaret Jane Radin; and former University of California Hastings College of the Law Dean Mary Kay Kane have also been interviewed.

“We're a broad-tent project,” Failinger said Wednesday. “We do try to get the women who have been important historical figures because they have been deans, or important figures in feminist jurisprudence. But we've been trying to get interviews with women who have all different kinds of career paths.”

Time is of the essence. The first significant wave of women legal academics, who like Kay began teaching in the 1960s, are retiring or passing away. (Women trailblazers like Armstrong predate Kay's cohort, but their numbers are miniscule.)

Five of the completed videos are currently available on YouTube, while many others are in various stages of production. The AALS plans to create a website that will make all the videos available in one place.

The American Bar Association is pursuing a similar but separate project dubbed the Women Trailblazers in the Law Oral History Project, which includes oral histories with more than 100 women lawyers, judges and law professors. Stanford Law School's library is hosting the interviews on a website.

One topic that comes up regularly in the interviews of women academics is the challenges of motherhood—particularly balancing teaching and pregnancy. Ginsburg said in her interview that she was reluctant to reveal her pregnancy in 1965, because she wasn't tenured and had only annual contracts. She borrowed clothing from her mother-in-law to obscure her pregnancy and didn't disclose it until her contract was renewed for the coming year.

Julie Greenberg, professor emeritus at Thomas Jefferson School of Law, in her interview recalled a former boss at the University of San Diego School of Law telling her she could “take a few days off” to give birth. She left the school instead.

Carrie Menkel-Meadow, a professor at the University of California Irvine School of Law, has been teaching law since 1974 and shared her experiences in an oral history interview. She also spoke on the AALS panel, recalling that many of the women she entered the academy with—herself included—never had children.

Early women law professors also shared stories of withering evaluations from students who did not want a female professor and male students who challenged their expertise and authority in the classroom. Those dynamics persists for many women professors today, the panelists said.

The women who have been approached to sit for oral history interviews generally have welcomed the opportunity, according to Failinger.

“Most of these women feel very gratified that someone is paying attention to them as a historical figure and an important person in the history of legal education,” she said. “Many of them have not full reflected on how the pieces of their own history have come together to where they are, and they find that fulfilling.”

Lisa Mazzie, a professor at Marquette University Law School who has conducted numerous oral history interviews, said she has found inspiration in those talks.

“There's a little bit of, 'You can get there from here' in all of their stories,” Mazzie said. “Listening to these women talk about why they went to law school—especially at the time they went—was really amazing and interesting. Their stories really resonate.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Right Amount?: Federal Judge Weighs $1.8M Attorney Fee Request with Strip Club's $15K Award

Kline & Specter and Bosworth Resolve Post-Settlement Fighting Ahead of Courtroom Showdown

6 minute read

12-Partner Team 'Surprises' Atlanta Firm’s Leaders With Exit to Launch New Reed Smith Office

4 minute read

Morgan Lewis Shutters Shenzhen Office Less Than Two Years After Launch

Trending Stories

- 1Critical Mass With Law.com’s Amanda Bronstad: LA Judge Orders Edison to Preserve Wildfire Evidence, Is Kline & Specter Fight With Thomas Bosworth Finally Over?

- 2What Businesses Need to Know About Anticipated FTC Leadership Changes

- 3Federal Court Considers Blurry Lines Between Artist's Consultant and Business Manager

- 4US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

- 5White & Case KOs Claims Against Voltage Inc. in Solar Companies' Trade Dispute

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250