Skilled in the Art: What's ZUP With Obviousness? Will AI Make Everything Obvious?

Is this the case that wil straighten out the Federal Circuit's law of obviousness"

January 25, 2019 at 05:09 PM

9 minute read

Welcome to Skilled in the Art. I'm Law.com IP reporter Scott Graham. Today I've got a look at a wakeboard inventor's longshot bid to reset the law of obviousness. Or at least to reset it until intelligent machines take over the invention process, at which point everything will become obvious, according to an academic's provocative argument. Pull up a virtual chair and let's chat. As always you can email me your thoughts and follow me on Twitter.

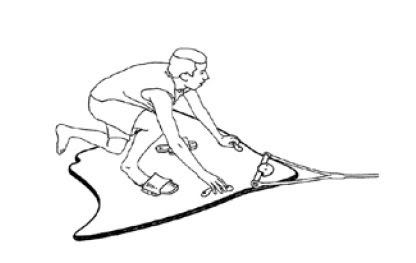

The ZUP board, as illustrated in U.S. Patent 8,292,681.

The ZUP board, as illustrated in U.S. Patent 8,292,681.

What's ZUP With Obviousness at High Court?

A savvy patent litigator at a blue chip firm once told me that the Supreme Court is inevitably going to have to straighten out the Federal Circuit's law of obviousness. That was four years ago, and I'm still waiting.

Every so often I see a cert petition and think “maybe this will be the one.” Apple v. Samsung—not the design patent case, but the en banc decision I'll always think of as Mr. Toad's Wild Ride—was one such case, but the justices turned it away.

Now I'm looking at a decidedly low-tech case involving a small-time inventor. Glen Duff invented a wakeboard that he says made it easier for non-athletes to get upright while being towed by a motorboat. The ZUP board, as he calls it, employs a tow hook, handles and foot bindings to help the user maneuver from a prone position to a crouch to a standing position. He was assigned U.S. Patent 8,292,681.

Duff tried to sell his invention to Nash Manufacturing, which has been selling water recreation goods for 50 years. Negotiations broke down, and Nash began marketing a board that Duff claims infringes. U.S. District Judge Henry Hudson ruled, and the Federal Circuit affirmed by a 2-1 vote, that the '681 patent is obvious.

Previous boards had separately used tow hooks, handles and foot bindings. Simply combining them on a single board was obvious as a matter of law, the Federal Circuit ruled. It didn't matter that no one else had ever thought to do so. “The weak evidence of secondary considerations presented here”the long-felt, unsolved need in the industry for such a wakeboard—“simply cannot overcome the strong showing of obviousness,” Chief Judge Sharon Prost ruled.

Certiorari is always an uphill battle at the Supreme Court. But here's why I think ZUP v. Nash Manufacturing might have a chance:

➤ The legal theory is simple. As argued in Judge Pauline Newman's dissent, secondary considerations such as long-felt need should be on equal footing with the other Graham factors such as the difference between the claimed invention and the prior art. “The requirement that the secondary considerations 'overcome' the conclusion based on the first three factors is incorrect,” Newman wrote. “The obviousness determination must be based on the invention as a whole including the evidence of all four Graham factors.”

➤ The siren song of the small inventor. ZUP's petition states that Duff developed the board for family motorboat outings, then for groups from their church. Duff alleges that when he confronted Nash's CEO at a surf expo about their dispute, the CEO told him “Get over it,” and that patents are meaningless in the water recreation industry. An inventors group including Josh Malone of the water balloon wars has filed an amicus brief in support of cert.

➤ Newman's voice has been getting heard lately at the Supreme Court. Since Neil Gorsuch joined the court, Newman's dissents have led to one reversal (SAS Institute v. Iancu) and another cert grant (Return Mail v. U.S. Postal Service).

➤ Ancient precedents. ZUP counsel Matthew Wawrzyn of Wawrzyn & Jarvis is asking the court to apply the obviousness framework from an 1851 Supreme Court precedent. That's catnip for this Supreme Court!

Everything Is Obvious, in an AI Way

While ZUP is looking back to the 19th century, Ryan Abbott is looking ahead to what an obviousness test might look like once intelligent machines take over more of the world's inventing.

In his recent law review article Everything Is Obvious, the Surrey School of Law and UCLA medical professor argues that once inventive machines become the standard means of research in a field, “the skilled person should be an inventive machine.” That would render more inventions obvious.

“To generate patentable output, it may be necessary to use an advanced machine that can outperform standard machines, or a person or machine will need to have an unusual insight that standard machines cannot easily recreate,” Abbott argues. That insight might come from access to specialized, non-public sources of data.

“Taken to its logical extreme, and given there is no limit to how sophisticated computers can become, it may be that everything will one day be obvious to commonly used computers,” Abbott writes.

Round 2 for Oracle v. Google at High Court

The ZUP case involves small companies, low-profile attorneys and a fairly remote chance of landing on the high court's docket. At the opposite end of the spectrum in all three respects is the copyright battle over application program interfaces between Oracle and Google.

Four years ago there was enough interest at the Supreme Court on the copyrightability of software interfaces for the justices to request the solicitor general's views. Now Google is raising that still-unresolved issue again, along with the proper application of the fair use doctrine in the context of computer code.

“Google has never disputed that some forms of computer code are entitled to copyright protection,” the company states in its cert petition filed Thursday. “But the Federal Circuit's widely criticized opinions—in an area in which that court has no specialized expertise—go much further, throwing a devastating one-two punch at the software industry.”

Williams & Connolly partner Kannon Shanmugam is counsel of record for Google. Goldstein & Russell; Keker, Van Nest & Peters; King & Spalding and Kwun Bhansali Lazarus are also on the petition.

In a written statement, Oracle GC Dorian Daley dismissed Google's petition as “a rehash of arguments that have already been thoughtfully and thoroughly discredited.” Google's true concern is “the unfettered ability to copy the original and valuable work of others for substantial financial gain.”

My ALM colleague Ross Todd has more details here.

PTAB Sovereign Immunity Case at High Court

They've argued to the PTAB. They've argued to district court and the Federal Circuit. And now the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe and Allergan are making their case to the Supreme Court that the Patent Trial and Appeal Board must recognize sovereign immunity in America Invents Act proceedings.

“This court should grant review to decide whether IPRs are the type of proceeding in which Indian tribes, state universities, or indeed any sovereign entity may assert sovereign immunity,” the tribe and Allergan argue in a December cert petition.

Jonathan Massey of Massey & Gail is counsel of record and joined by attorneys from Covington & Burling and Shore Chan DePumpo, among others. The case poses a final test of whether Allergan can shield its Restasis patents from PTAB review through a complex licensing deal with the tribe. Critics have accused Allergan of “renting” tribal immunity, though scholars including Laurence Tribe and Erwin Chemerinsky have defended the deal.

The key to the case—or at least certiorari—is going to be whether the Supreme Court considers IPRs similar enough to civil litigation for sovereign immunity to attach. As Judge Kimberly Moore pointed out in her opinion for the Federal Circuit last year, there's tension between the Supreme Court's 2018 opinions in SAS Institute v. Iancu, which stressed that the IPR procedure “mimics civil litigation,” and Oil States v. Greene's Energy, which said that IPR is merely “a second look at an earlier administrative grant of a patent.” Moore concluded that IPRs are a hybrid of the two.

Massey argues that's wrong. “There is no such 'tension' and no conflict in this court's decisions,” he writes. “Neither SAS nor Oil States referred to IPRs as a 'hybrid proceeding.'”

That's true as far as it goes, but the Supreme Court did use the phrase “hybrid proceeding” to describe IPRs just two years ago in Cuozzo v. Lee.

For Moore, the PTO director's broad discretion over IPR proceedings tipped the balance toward administrative review. Massey calls that “an exaggerated view of the director's role in IPRs” that was rejected in SAS.

“The petition is formulated, drafted, and filed by a private party, not the PTAB,” he writes.

Making Lemonade From Sovereign Immunity Lemons

Regardless of whether it gets Supreme Court review, the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe is getting some mileage from Judge Moore's opinion.

The tribe last week asked PTO Director Andrei Iancu and the PTAB to exercise their discretion to reject a series of IPRs that Microsoft filed against the tribe, in part based on sovereign immunity. Though it considers Moore's opinion wrongly decided, the tribe cites the rationale that the PTO director bears political responsibility for determining which cases should proceed, and can take into account a patent owner's sovereign status.

“Accordingly, the tribe respectfully requests that the director exercise his discretion to deny this petition based on the tribe's status as a sovereign,” Shore Chan partner Alfonso Chan wrote in a preliminary response to Microsoft's petitions filed Jan. 15.

The tribe is teaming up with SRC Labs, a provider of supercomputing technology to defense contractor Lockheed Martin, to sue Microsoft. They allege that Microsoft “shamelessly copied and claimed credit” for SRC's advances in field programmable gate arrays.

Microsoft, represented by Sidley Austin, has filed 10 IPRs challenging six different patents. It argues in one that the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers described the technology before it was patented. If that prior art had been before the patent examiner, the PTO never would have issued the patent, it says.

As with the Allergan arrangement, SRC has assigned the patents to the Saint Regis tribe while getting a license back. The tribe says the money it earns from such deals strengthens the tribal economy while supporting housing, employment and education.

That's all from Skilled in the Art this week. I'll see you all again on Tuesday.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Skilled in the Art With Scott Graham: I'm So Glad We Had This Time Together

Design Patent Appeal Splinters Federal Circuit Panel + Susman Scores $163M Jury Verdict + Finnegan Protects Under Armour's House

Trending Stories

- 1States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 2Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 3Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 4Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

- 5Securities Report Says That 2024 Settlements Passed a Total of $5.2B

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250