There Isn't Going to be an Elite Transatlantic Law Firm Merger

Why? Because US firms don't need one, and UK firms can't afford one

February 14, 2019 at 08:29 AM

5 minute read

There are two reasons, each dispositive in its own right, that an elite transatlantic law firm merger isn't going to happen: the elite US firms have sufficient presence in London not to want one, and the UK firms have insufficient profitability to afford one. Might a UK firm merge with a US player below the elite? Possibly, but the practice synergy is much weaker, and the viable US firms would not have the prestige to be compelling to the elite UK firm's partners. If this latter didn't scuttle the combination, it would sabotage the integration.

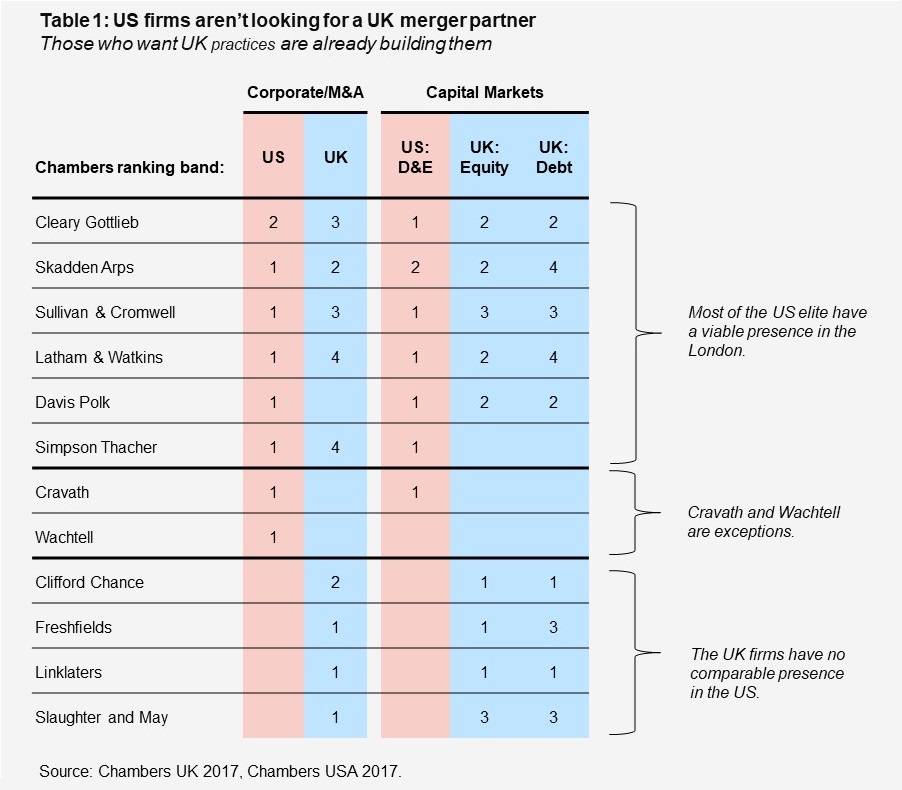

Let's start with the U.S. elite. To define this group, we looked at the firms with Band 1 Chambers USA Nationwide rankings in either of corporate law's two most prestigious practices: corporate/M&A and capital markets. This identified the eight firms shown in Table 1; the table also shows these firms' UK rankings for the comparable practices. Six of the eight firms have ranked practices in the UK. For these, merging with a UK firm is a less compelling way to bolster these practices than is organic growth and lateral acquisition. The two US firms that don't have a ranked London presence, Cravath and Wachtell, are unlikely to want a London merger partner. As high-end specialists, their business models require they be independent of any one London firm so that they can act as US counsel on mega matters to a myriad of London firms. Hence, there's no compelling logic for an elite US firm to find a London merger partner.

If we define the UK elite in an analogous manner, i.e. firms with Band 1 Chambers UK rankings for the same two practice areas (allowing that, unlike in the US, London capital markets rankings are in separate debt and equity components), we get the four firms shown, along with their US rankings, at the bottom of Table 1. Unlike their US counterparts, these firms do not have ranked US practices (after many years of trying for some).

Three of these UK firms (Clifford Chance, Freshfields, and Linklaters) have broad global footprints. It is easy to imagine that they would value a stronger US (particularly New York) presence and see a transatlantic merger as a means to achieve this: it would give them a share of the high-priced US market albeit at the cost of some referral business from New York firms. For the fourth firm, Slaughter and May, the assessment is probably different: unlike the others, they have remained largely UK focused. Their positioning in London is analogous to that of Cravath and Wachtell in New York—high-end specialists, available to act as UK (and European) counsel on mega matters to all US firms.

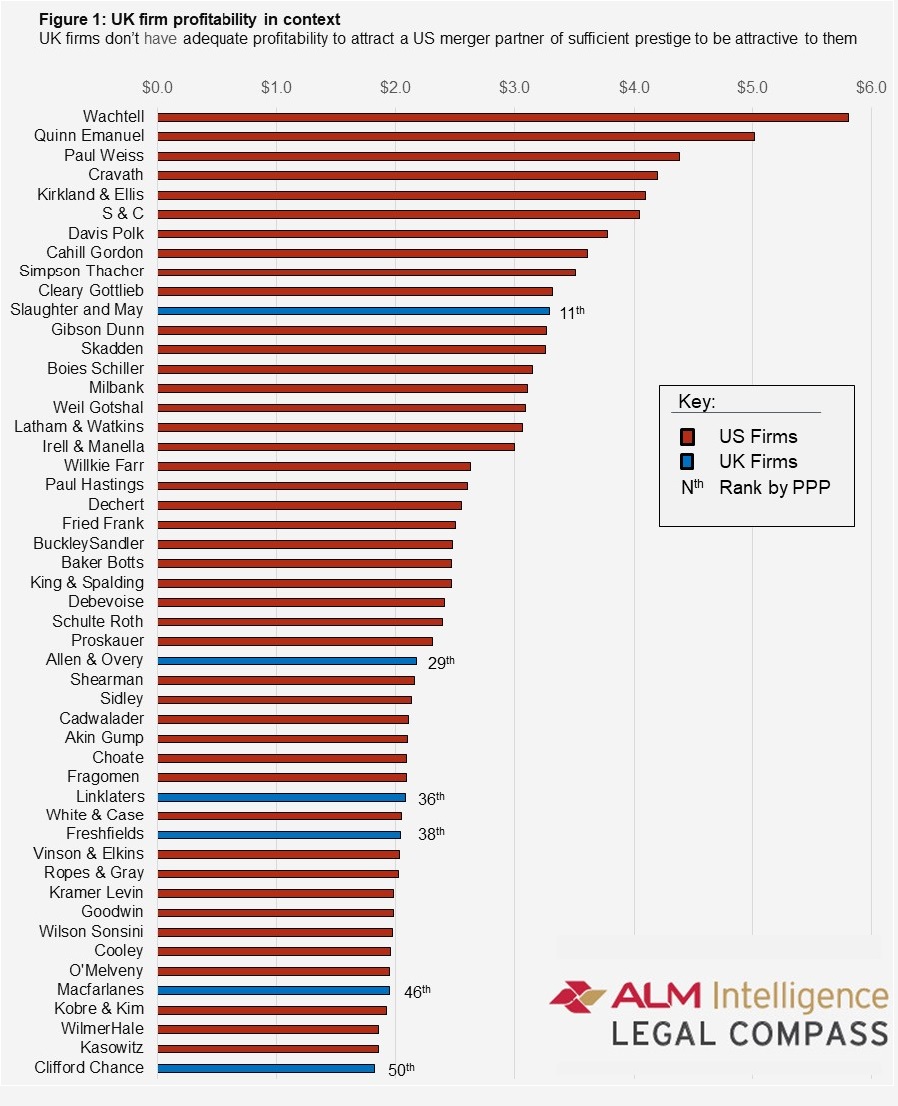

So, could the London troika of Clifford Chance, Freshfields and Linklaters find an elite combination partner in New York? It's very unlikely; even if a US firm thought a combination attractive, the UK firms are simply not profitable enough to be viable combination partners. Figure 1 shows how the most profitable UK firms would rank among US firms by profit per equity partner (PPP). Linklaters, Freshfields, and Clifford Chance would rank as 36th, 38th and 50th by PPP, respectively. The one UK firm with sufficiently strong PPP to be a viable merger partner—Slaughter and May at 11th—would be ill-served strategically by a combination.

I should note that the PPP comparison here is not a spurious exchange rate artefact. Rather than a spot rate, the analysis uses the long-run equilibrium rate and applies it to both non-sterling revenues being consolidated onto the UK firms' Companies House reports and to the translation of the resultant sterling-denominated profitability into dollars.

We may see an elite UK firm combine with a US firm ranked somewhere between 30th and 50th by PPP but it's unclear how successful this would be. The strategic logic wouldn't be straight forward as the US firms in this profitability band don't have sufficient strength in the flagship corporate/M&A and capital markets practices to deliver real synergy. In theory, the newly-acquired US firm could be used as an at-scale platform on which to build a presence in these practices through lateral hiring; in reality, elite New York lawyers are far too prestige aware to find a US firm in this PPP band a compelling new professional home. A US combination would round out the geographic presence of the London firms, but this would come at a cost in the form of reduced referrals and is of questionable incremental value to clients. And then, of course, there are the human aspects: partners at the elite UK firms are unlikely to be flattered by the prestige of the US firms who would find them an attractive combination partner. If their disdain didn't prevent the deal from happening, it would doom the integration.

There may have been a time when an elite UK firm could have merged with an elite US firm but, if so, it's in the past. There may be a time when an elite UK firm could merge with a below-the-elite US firm but if so it's in the distant future—it'll take UK partners a long time to accept the reality of who their peer US firms are.

Hugh A. Simons, Ph.D., is formerly a senior partner and executive committee member at The Boston Consulting Group and chief operating officer at Ropes & Gray. He writes about law firms as part of the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program. He welcomes readers' reactions at [email protected]

More information on the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program can be found here.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Big Law Sidelined as Asian IPOs in New York Are Dominated by Small Cap Listings

Greenberg Traurig Combines Digital Infrastructure and Real Estate Groups, Anticipating Uptick in Demand

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Investor Sues in New York to Block $175M Bitcoin Merger

- 2Landlord Must Pay Prevailing Tenants' $21K Attorney Fees in Commercial Lease Dispute, Appellate Court Rules

- 3Compliance with EU AI Act Lags Behind As First Provisions Take Effect

- 4NJ's Pardons and Commutations A Model for the Federal System

- 5As Political Retribution Intensifies, Look to Navalny's Lawyers

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250