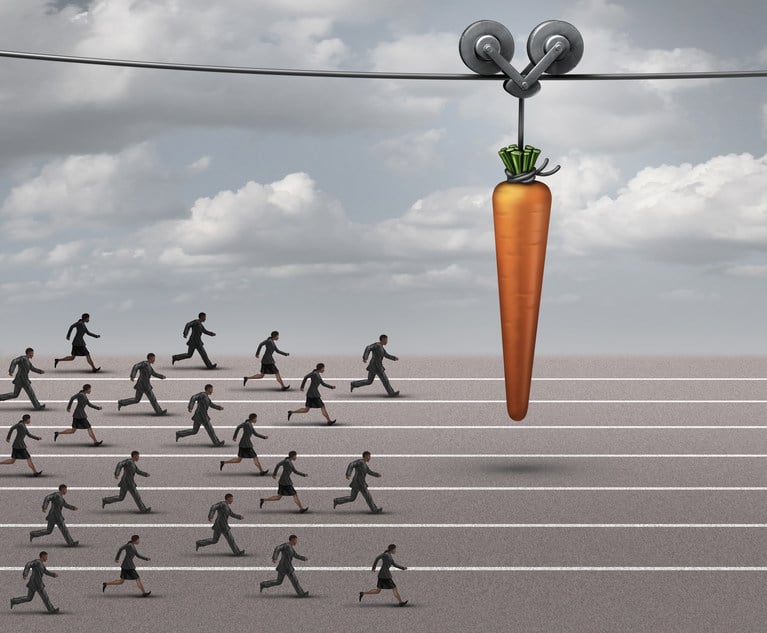

While Everyone Else is Busy Bragging, the Smart Law Firms Let Data Do the Talking

While just about every midsize law firm prides itself on the "value" it offers clients, likely far fewer could readily present data to back up the bravado.

February 15, 2019 at 09:15 AM

5 minute read

Credit: Vintage Tone/Shutterstock.com

Credit: Vintage Tone/Shutterstock.com

Editor's Note: This story is adapted from ALM's Mid-Market Report. For more business of law coverage exclusively geared toward midsize firms, sign up for a free trial subscription to ALM's weekly newsletter, The Mid-Market Report.

Businesses in just about every conceivable industry, from baseball to breadmaking, are using data analytics to a gain a competitive edge. The legal industry is no exception, but a lot of midsize law firms are behind the curve in that regard, according to James Goodnow, president and managing partner of Fennemore Craig in Phoenix.

Goodnow said his firm has seen “a huge uptick” in the use of data analytics by its clients to measure the cost-effectiveness of outside counsel. That, in turn, has prompted Fennemore Craig to “heavily invest” in its own data analytics tools to gauge efficiency and productivity within the firm.

Lawyers are still in the relationship business, but the relationships are getting more complicated.

While just about every midsize law firm prides itself on the “value” it offers clients, likely far fewer could readily present data to back up the bravado. But the insights gleaned by drilling down into the information that most firms already have access to—how long matters typically take to complete, competitors' rates, the number of partners and associates needed to appropriately staff a matter, etc.—can be used to both to improve internal processes and to transform the concept of value into something less nebulous and more concrete for clients, according to firm leaders and consultants.

“I think if midsize firms, in particular, don't get with the program and start understanding pricing and efficiency, work is going to start going away,” Goodnow said.

But he also acknowledged that it can be difficult to convince partners at smaller firms that spending significant money on data analytics technology is a worthwhile investment. At Fennemore Craig, he said, getting internal buy-in has been the result of “an important education process” aimed at explaining how the technology will ultimately help grow market share, revenue and profits by improving efficiency and client service.

It's potentially an even tougher sell for firms whose clients haven't already signaled an interest in a more data-driven approach to purchasing legal services. However, those are the firms that may also stand to gain the most by giving their clients information they never knew they needed.

While some midsize firms, like Goodnow's, have witnessed their clients relying more heavily on data to make legal spend decisions, Rees Morrison, a principal at legal consultancy Altman Weil who advises legal departments on cost control, said that's not the norm.

Morrison acknowledged a gradual upswing in the use of data analytics among some in-house counsel. But he said it's been his experience that the majority of legal departments in the U.S., and particularly those at mid-market companies, are not spending much time crunching numbers to find the best value available in the legal services marketplace.

“Most of the law departments in the U.S. have five lawyers or fewer,” he said. “They don't have the data analytics [capabilities]. They don't have much data, in some ways.”

For midsize firms, that creates a marketing opportunity, Morrison said. A firm can differentiate itself from the competition by doing its own analysis of the marketplace to show current and prospective clients how it stacks up to competitors on metrics like price, staffing and results, he explained. Firms can use that data in their responses to requests for proposals from potential clients as well as to strengthen and possibly broaden existing client relationships, according to Morrison.

And, Morrison added, legal departments appreciate that quantitative approach.

An emphasis on data can give law firms the competitive upper hand in an industry where marketing still mostly involves “beating your chest and saying, 'We handled this matter and that matter and we're really good at handling matters,'” Morrison said.

For midsize firms, and especially those competing in more niche practice spaces, a data-driven approach to demonstrating value, as well as expertise in a given industry, “may be a more targeted arrow to shoot,” Morrison added, “and they need that.”

“They cannot just say, 'We are good at garbage recycling litigation,'” he said.

And if competition from other law firms isn't enough to convince firm leaders that they need to pay more than lip service to the concept of value, the rise of alternative legal service providers, whose business models are predicated on efficiency, should be more than enough motivation, Goodnow warned.

Those firm leaders who continue to underestimate the threat posed by ALSPs have likely either already lost work to them or are on the verge of losing it—they just haven't realized it yet, Goodnow said.

“When a client diverts work to another firm or ALSP, they're generally not emailing you about it,” he said. “The work is diverted and if you're not paying attention, you don't even know it.”

As Morrison said, data analytics can give midsize firms the “targeted arrow” they need to do battle in an increasingly competitive legal services market—but knowing where to shoot that arrow is another matter. Next week's installment will look at the importance of practice and market focus in avoiding a midsize firm “identity crisis.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

How This Dark Horse Firm Became a Major Player in China

Colgate Faces Class Actions Over ‘Deceptive Marketing’ of Children’s Toothpaste

Internal Whistleblowing Surged Globally in 2024, So Why Were US Numbers Flat?

6 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 2No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 3Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 4Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 5Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250