Divergent Perspectives on Law Firm Innovation

Innovation is seen very differently by law firm leaders, partners, and associates

February 21, 2019 at 11:39 AM

14 minute read

In a previous article posted on law.com, I discussed the findings of late 2018 survey I conducted on the state of innovation in the legal market. At the end of the survey, to delve deeper into the DNA of the data, I ask for demographic information (firm size, revenue, footprint, revenue per lawyer, etc.) and/or the name of their firm so that I might fill in the data, myself. This allows me to compare data across demographic strata in hopes of finding “best practices” or gaps where improvements can be made. Specifically, I wanted to compare answers in three areas: (i) the various employment classes – leadership versus partners versus associates, (ii) RPL – “lower” versus “higher” and (iii) geographic footprint – international/global, domestic and regional. We'll start with the classes.

Homogeneity of the Classes – Leadership, Partners and Associates

Late last year I presented the findings of this survey at, and moderated a panel on legal innovation initiatives for, a legal innovation summit at Suffolk Law School in Boston. Our panel was early in the summit, but not so early that I wasn't able to see a common theme in both the presenters' and attendees' language: that of “culture.” In fact, I heard it talked about enough that in the middle of our panel I queried the audience: “Can you raise your hand if you find culture to be one of the top, if not the top, challenge you face from an innovation perspective”? We didn't take a formal tally but the vast majority of the attendees raised their hands. It was an interesting and somewhat clarifying moment. Culture is a hot topic, particularly where innovation is concerned.

Defining culture can get a bit tricky, but it could be accused of being the glue that binds an organization together. And the more homogeneous the shared norms, belief systems, values, etc., the more functional and effective is the group. In fact, a group's “strength” can be measured by the consistency of actions and answers to group-oriented tasks and questions across the organization's entire platform. In a law firm's case, this would be from leadership to partners to associates and even down to administrative assistants. This may not be good news for law firms, however.

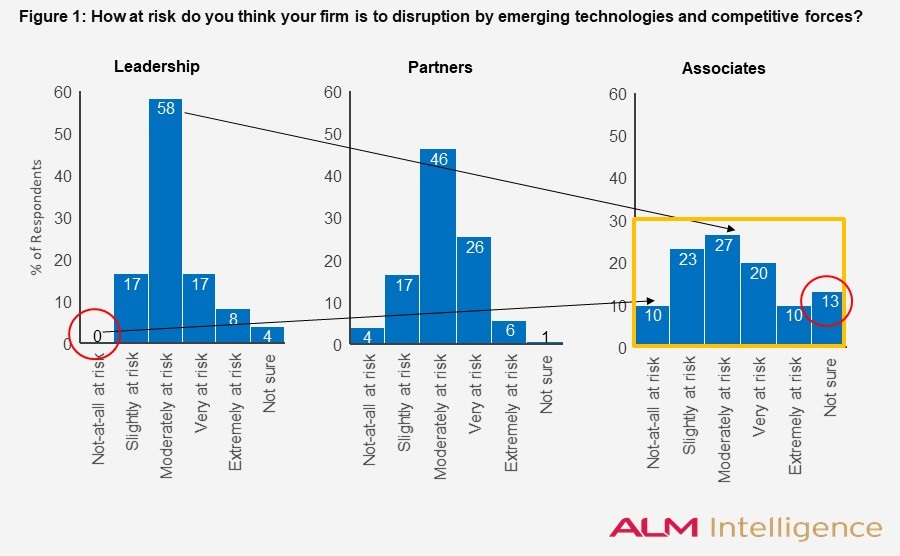

When asked about their firm's vulnerability to disruption by emerging technologies and competitive forces, there were some discrepancies.

While there is a consistent concentration around “Moderately at risk” within each of the classes, you can see a general flattening of the curve, or diffusion of consensus, as we move from leadership to partners to associates. While no leadership at all found their firms to be completely out of harm's way – which I expected – there is an increase as we move to partners and then to associates, which came in at 10%. This gives us what I am calling ascending thoughts of immortality, something rooted in, for lack of a better term, ignorance. There isn't a firm on the market that is wholly invulnerable to innovation in some way. Lastly, the associate population shows the highest percentage of “Not sure” (see ALM Intelligence's Associate Technology Survey to see how law firms rank in terms of the satisfaction of associates with their firm's technology).

In describing their firm's innovation achievements, there is a general increase in the choice of “Fairly ad-hoc” as we move from leadership (25%) to partners (~34%) to associates (40%). And there is a huge gap between leadership and partners, in particular, where “First mover” status is concerned (50% and ~22%, respectively).

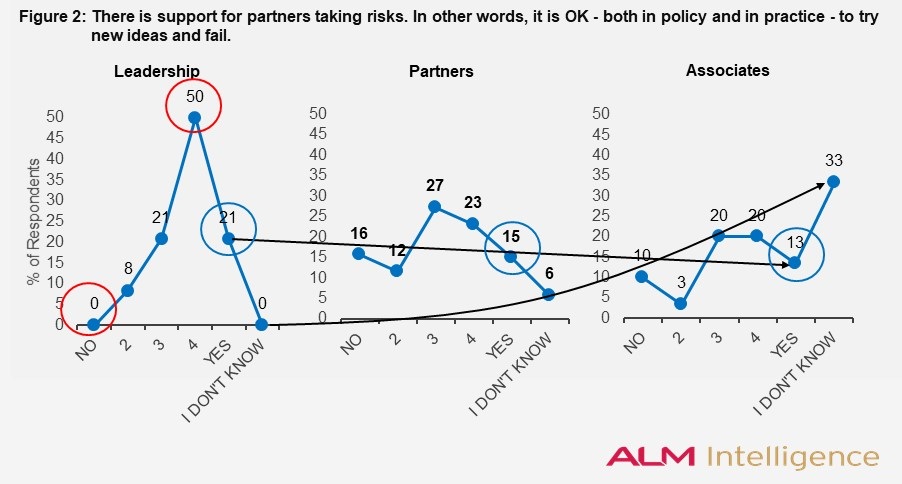

Does their firm support risk? For many, unfortunately, no. Most interesting – at least to me – is leadership's answers regarding “No” in relation to 4. No one was going to actually say “No”, because, whether it is true or not, how could any leadership openly admit that their firm won't allow some coloring outside of the lines? Further, in reading the tea leaves about the huge concentration in 4 (50%!), I'd bet that they really wanted to say “Yes”, but just couldn't bring themselves to outright lie. That said, we find a general but gentle decline in “Yes” from leadership to partners to associates, and a sweeping upward curve from leadership to partners to associates for “I don't know” (from 0 to ~6 to ~33%! – a massive increase).

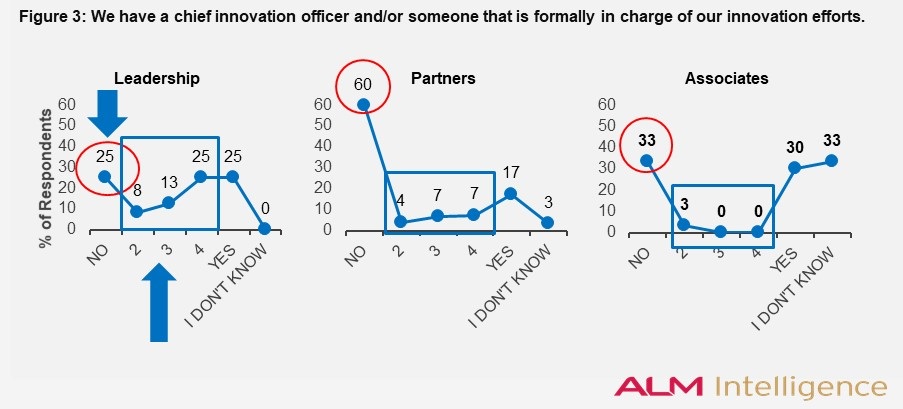

Regarding whether someone is formally in charge of innovation or not, leadership had the lowest rate of “No” and the highest rate of “Kind of.” This is surprising, as this question lends itself to a digital answer – “Yes” or “No.” This tells us that either leadership is further out of the loop than the rest of the firm – which is unlikely – or they have a guilty conscience and just couldn't say “No.” Either way, there is a huge discrepancy between leadership and partners, in particular; and associates dramatically outpace leadership and partners in the “I don't know” category.

This is a fairly constant theme. To most questions in the survey, we found sizable disparities between one or more of the classes. This is important. Law firms have been making significant changes to their organization structure over the past several years. Forty-five percent of Am Law firms have increased the share of associates at their firm since the downturn. Seventy-seven percent have increased the percentage of non-equity partners (see a graph of the leverage of Am Law 200 firms and their percentage of non-equity partners in Legal Compass). Though the disparities between these groups could use some further investigation, I am confident that internal communication is mostly, if not entirely, to blame. Where the process of imbuing innovation into the firm's culture is concerned, this is a real issue. A functional group and culture require, among other things, robust, clear and consistent channels of communication to galvanize their methods of operation and make them automatic. There should be a common language (jargon, identifiers, idioms and parlance, etc.) and commonly held conceptual categories among the members that allow for the effective transmission of information (ways of classifying various things throughout the firm – responsibilities, in particular). Further, consistent communication and clear, unambiguous messages that permeate through the entire organization – including associates! – are an important part of the glue by which the entire group's culture is held together. Some of the best firms in the business invest heavily in their associates. Let's not forget one of the primary concerns of the “Cravath system,” which is to thoroughly develop their newer generations. This is certainly an area that firms can begin to dissect and target for innovation.

Footprint

How do the larger firms think, set their cultures around, and invest in innovation compared to their domestic and regional counterparts? I think it reasonable to assume that international firms – certainly global firms – suffer more challenging and complex pressures than their domestic and regional counterparts (see The Global 200 ranking for a list of the largest 200 law firms). Taking this a step further, I expect them to be a bit more serious about and invested in innovation. That said, I found some significant but predictable differences and some surprises.

When considering whether being innovative is important to their firm's long-term growth and prosperity, International/Global firms (IGs) concentrated in “Very important” to “Extremely important” (~71%, cumulatively). Surprisingly, they were lower than domestics (~78%) and regionals (~87%). I wonder if this isn't because the IGs have a more demonstrable differentiator – their footprint – than the domestics or regionals, who might rely more on innovative advancements to achieve differentiation. This answer stands in contrast to those of the rest of the questions.

When asked to describe their firm's innovation achievements, IG's concentrated in the “Fast follower” and “First mover” categories (~ 61%, collectively) whereas domestics and regionals concentrated in “Fairly ad hoc” and “Still in initial development” (~78% and ~87%, respectively).

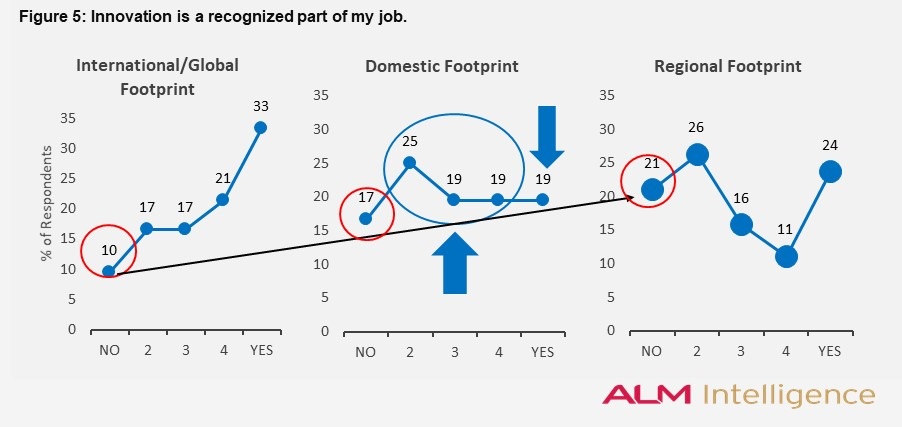

When describing whether innovation is a recognized part of their jobs, we see a gradual increase in “Nos” from IGs to domestics to regionals. And at ~33%, IGs have the highest rate of “Yes.” Surprisingly, at ~24%, regionals came in ~4% above domestics. And further, domestics had the highest concentration in the middle – the “Kind ofs” – with ~64%. (Note: There were no “I don't know” answers, here, despite it still being an option.)

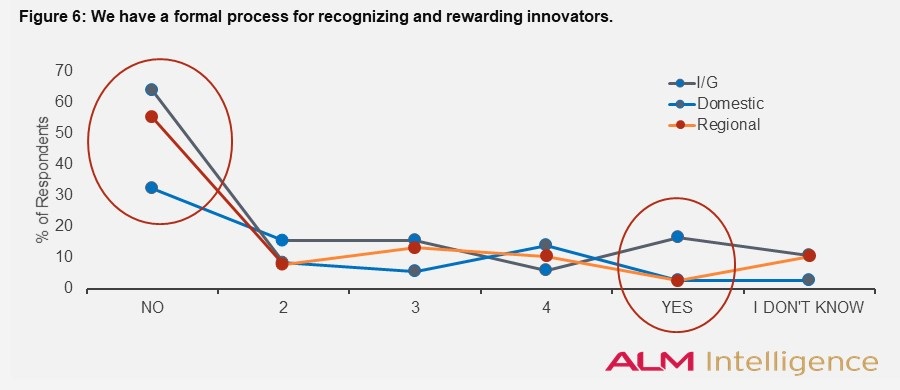

Regarding having a formal process for recognizing and rewarding innovators: IGs recognize this – “Yes” – at a mere 17%. But when compared to the domestic and regional firms – both of which only came in at ~3% – IGs are 5.5 times higher than their counterparts. Also, ~32% of IG's chose “No”, considerably less than their smaller competitors – domestics (~64%) and regionals (~55%).

Regarding the following, as I expected IGs have the lowest rate of “No” and the highest rate of “Yes” when compared to the domestics or regionals:

- Maintaining a CIO or otherwise having someone formally in charge: “No” – ~37%; “Yes” – ~29%.

- Having an innovation strategy: “No” – ~13%; “Yes” – 25%.

- Having a separate pool of funding: “No” – ~26%; “Yes” – 19%.

- Having formally defined innovation processes: “No” – ~39%; “Yes” – ~27%.

In short, we can see that IGs, while considering innovation a bit less critical to their success than domestics and regionals, actually embrace, and take the investment in, innovation more seriously. This is an important trend for firms to understand. Forty-eight percent of Am Law 200 firms have become more global since the downturn, measured by the percent of lawyers outside of the United States. Seventy-one percent of firms have increased their domestic footprint over the same period (see the Barbarians in the Gate report for more detail on law firm's geographic expansion).

RPL

Revenue per lawyer is the metric that the American Lawyer has “long regarded as the most reliable measure of a firm's financial health.” Who am I to argue? And I think most of the legal market would agree (see a graph of the revenue per lawyer of the Am Law 200 in Legal Compass). After all, what firm would want their RPL to be lower? With that in mind, I was curious to know the esteem to which the higher RPL firms held innovation (those greater than $830K) in comparison to their lower RPL counterparts (those less than $830K).

When asked how important being innovative is to their firm's long-term growth and prosperity, we found that lower RPLs concentrate around “very important” (~49%) where higher RPLs concentrate around “extremely important” (~42%).

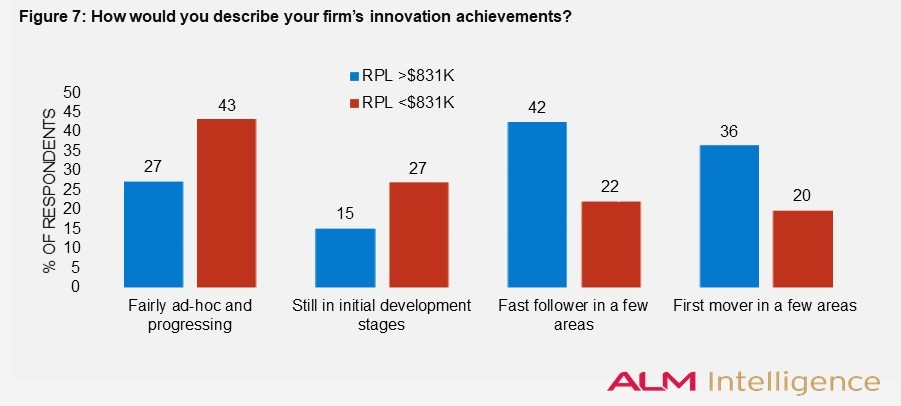

Higher RPLs generally describe their firm's innovation achievements as first, being “Fast followers” (42%) and then “First movers” (36%). Lower RPLs took a different tack. They concentrated around “Fairly ad-hoc” (43%) and then “Fast follower” (~22%).

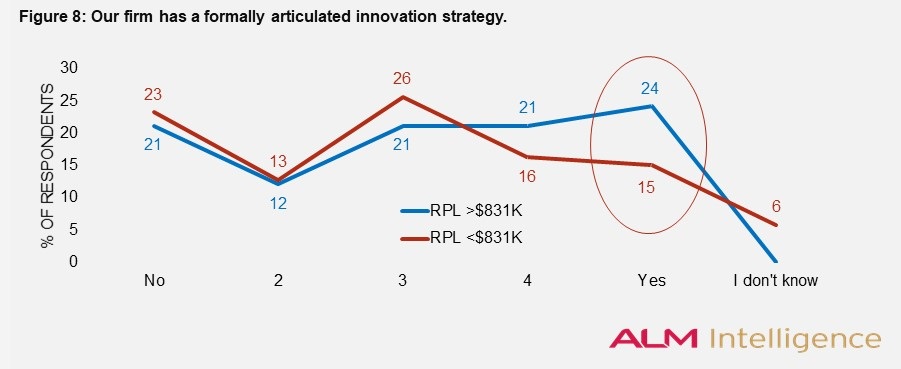

Higher RPL firms recognized innovation as a part of their attorney's jobs at ~42%, a much higher rate than lower RPL's ~23%. Higher RPL firms have someone formally in charge of innovation at a much higher rate – only 36% said, “No” compared to 60% of the lower RPLs and 30% said, “Yes” compared to only 10% of the lower RPLs. More of the higher RPLs have a formally articulated strategy: ~24% said, “Yes” compared to only ~15% of lower RPL's.

Lastly, with 27% saying “Yes” and ~42% saying “No”, more of the higher RPL's have formal processes for phases of their innovation process than their lower RPL counterparts, which are ~14% and ~52%, respectively.

As a quick, high-level summary, it seems as though, on the whole, the higher RPL firms take a more aggressive stance toward, and better invest in, innovation.

Summary

So, what are we to take from this? I think there are some obvious lessons.

First, while we aren't at the starting line, the industry still has a long way to go. And this starts with the industry's culture. In my experience “culture” is often a misused term as it comprises a number of variables that, unless you've studied it, avoid detection. While we won't delve too deeply, suffice it to say that an institution's “culture” is a blueprint, per se, that makes usable the set of beliefs, values, assumptions, tools, methods of operation, etc., that over the years have proven to be most effective in ensuring a group's survival and competitive advantage in its particular environment. And certainly, the harsher the environment, the more visceral, durable and homogenous are those “things” that the culture comprises.

In the case of the Suffolk Law School summit where the audience showed such interest in culture (which was composed of innovation professionals that work within and/or consult with law firms), my suspicion was that they wanted a higher rate of cooperation on, compliance with, and adoption of, innovation initiatives. Subsequent conversations verified that. And in the sense that a firm's culture is indeed a “blueprint”, I'm sure that it would be helpful to have a culture that, for instance, is built on values and beliefs that support, are invigorated by and ultimately foster the process of innovation.

Such a culture is often not the norm in law firms, however. Innovation is change; an event that most times is initiated by the whip rather than the carrot. To be direct, the legal market, despite the pressures it has suffered as of late, is and has been for many years a protected market. There may be a wolf trotting toward the doorstep, but it is relatively toothless – at least at the moment. A quick look at the P3 numbers of the Am Law 200 and the perpetually rising bill rates finds a very profitable industry, which, in and of itself can create significant inertia. Along with driving the process of innovation, the pressures of the market – “natural selection” – will break that inertia and invoke cultural change. But that is a slow process. The liberalization of the US legal market would greatly speed it up, but we shouldn't hold our collective breath.

So, where do we start to make a cultural shift? This brings us to my second lesson: while cash will always be King – i.e., it's tough to beat the leverage that compensation asserts on behavioral changes – communication comes in a close second, particularly where the process of shifting a culture toward innovation is concerned. In an interview I did with Chip Bergh for Forbes – the turn-around CEO for a (at the time) struggling Levi Strauss & Co. – he articulated a specific communication strategy that was one of the more important tools that he used to help evolve the culture of one of the oldest and most successful brands in the world. If it worked for them, it can work for your firm, too. So, your communication strategy should be taken most seriously and not just left to flourish or wilt as a product of chance. What messages are important? How are they communicated? Who communicates them? How often? How are you measuring their impact? Etc.

Third, and perhaps the most obvious, we can see that the more complex and financially successful (and potentially more evolved) firms think about, set their cultures around and invest in innovation in particular ways. If I am a firm leader that wants to institute cultural and practical change toward more aggressive innovation (or even just a partner or associate that wants the same), I would take this to heart. While the above information articulates the market's positions at a higher altitude, it can provide a template to begin building your own firm's plan.

David J. Parnell is an author and speaker, co-founder of the Legal Institute for Forward Thinking and founder of legal search and placement boutique True North Partner Management.

More information on the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program can be found here

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Big Law Sidelined as Asian IPOs in New York Are Dominated by Small Cap Listings

Greenberg Traurig Combines Digital Infrastructure and Real Estate Groups, Anticipating Uptick in Demand

4 minute read

Morgan Lewis Closes Shenzhen Office Less Than 2 Years After Launch

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250