Midsize Firms Learning to Compete With Big Law While Avoiding an 'Identity Crisis'

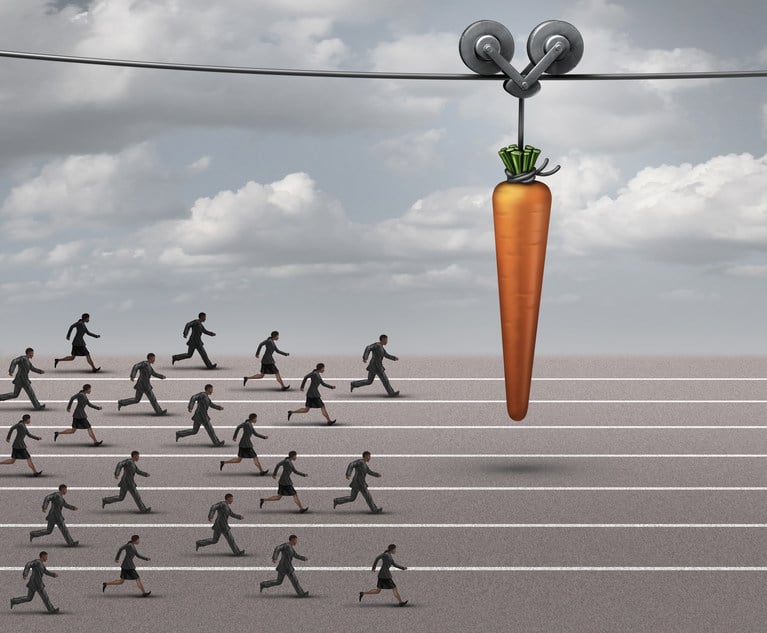

Given how radically the business of law has changed over the past decade, it can be tempting to measure midsize firms' success by how much market share they've been able to snatch from their larger or richer counterparts. But neglecting the mid-market client base your firm was built upon in the pursuit of "higher-end" work can be a dangerous proposition.

February 25, 2019 at 02:14 PM

5 minute read

Illustration by Wavebreak Media LTD

Illustration by Wavebreak Media LTD

Editor's Note: This story is adapted from ALM's Mid-Market Report. For more business of law coverage exclusively geared toward midsize firms, sign up for a free trial subscription to ALM's weekly newsletter, The Mid-Market Report.

In a presentation given at ALM's annual Legalweek conference in New York recently, Nicholas Bruch and Erin Hichman of ALM Legal Intelligence described a legal industry that's increasingly splitting into two segments—”bet the company” and ”run the company.”

Most midsize law firms—really, most law firms—would fall squarely into the latter category. But the quest for more “high-end” work, often from larger institutional clients, can sometimes blur the line between ambition and delusion, firm leaders warned.

“That's one of the mistakes midsize firms make,” said Marc Hamroff, managing partner of 70-lawyer Long Island firm Moritt Hock & Hamroff. “You have success in the mid-market and you say, 'Let me go compete with the 1,000-lawyer firms.' That's where they lose their core. We're not chasing the largest companies in the world if they don't fit with our core and space.”

In a report issued by Georgetown and Thomson Reuters at the beginning of this year, James Jones, a senior fellow at the Center for the Study of the Legal Profession at Georgetown University Law Center, cautioned mid-tier firms about straining to compete with wealthier firms that can afford to charge higher rates and pay higher associate salaries.

“We do not have one market for legal services anymore,” Jones said in an interview with The American Lawyer. “A lot of people have a really hard time being honest about where their services fall because the vast majority of American law firm services are in that big middle. And I've never met a lawyer who didn't like to think that he or she performed brain surgery. But you know, there just aren't that many big brain operations going on that clients are paying for.”

Still, given how radically the business of law has changed over the past decade, it can be tempting to measure midsize firms' successes by how much market share they've been able to snatch from their larger or richer counterparts.

But while every law firm leader interviewed for this series said the economic downturn opened doors to relationships with larger clients and offered opportunities to compete in a space that was previously the exclusive domain of Big Law, nearly every one of them was also quick to add that those new endeavors did not supplant or detract from their existing mid-market client base.

Bob Baradaran, managing partner of Greenberg Glusker, which has about 100 lawyers and a single office in Los Angeles, said his firm's clientele is a mix of high net worth individuals, large institutional clients and mid-market companies, with the mid-market companies accounting for the largest portion.

The firm's leverage model and low overhead are what allow it to serve that eclectic base, Baradaran said, which is why he sees little reason and has little desire to drastically expand Greenberg Glusker's head count and geographic footprint in the coming years.

“I think a lot of midsize firms are being run more like the national firms,” he said, describing smaller firms with lopsided associate-to-partner ratios needlessly spread across multiple offices and disparate practice groups. “Many of them are just smaller versions of the national firms. I sometimes call us a full-service boutique. We don't sell ourselves as being the same as a national firm, we don't try to operate like that. The best advice I can give is, 'Know what your model looks like and just be laser-focused on that.'”

Moritt Hock's Hamroff said the firm recently implemented a three-to-five-year strategic plan aimed at exactly that concept. Executing the plan, he said, requires the firm to ”understand what our business is and to what kind of clients we're found to be attractive—and in what industries—and to really focus on that and not try to be all things to all people.”

The firm has a wide range of practice areas, from litigation to commercial lending to copyrights, and counts among its industry focuses construction, equipment leasing, promotional marketing and vehicle leasing, along with serving financial institutions, startups and small businesses.

“That's our strategy: focus on our core,” Hamroff said. “At the same time, we try to look for growth opportunities.”

As a number of firm leaders noted, serving the mid-market and pushing into larger competitors' space need not be mutually exclusive concepts.

“I think it's one issue that midsize firms struggle with,” said James Goodnow, president and managing partner of 150-plus-lawyer Fennemore Craig in Phoenix. “I think particularly in today's times, with the volatility in the market, some midsize firms are having an identity crisis. They're saying, 'Do we want to go after the Fortune 500 and 100 companies and spend the time and expense to do that or do we want to go for the closely-held businesses?' I think the answer has to be both.”

Recognizing that, depending on context, a “midsize law firm” can be anything from from 50 lawyers to 500 lawyers, Paul Hughes, managing partner of 150-lawyer New Haven, Connecticut-based Wiggin and Dana, said he prefers to define the term as any ”firm of size and quality that clients will trust with sophisticated, important work.”

And just as pushing too hard to keep up with the Big Law Joneses can be a dangerous proposition for midsize firms, so can settling for “too much low-cost, competitive, rote work where the only difference [between firms] is price,” Hughes said.

“You can do that, but that's a recipe for shrinking profits, which over time leads to a shrinking talent pool,” he said. “You have to have the discipline to do less of that and not chase revenue for the sake of revenue.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

How This Dark Horse Firm Became a Major Player in China

Colgate Faces Class Actions Over ‘Deceptive Marketing’ of Children’s Toothpaste

Internal Whistleblowing Surged Globally in 2024, So Why Were US Numbers Flat?

6 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Bar Report - Jan. 27

- 2Cornell Claims AT&T, Verizon Violated the University's Wi-Fi Patents

- 3OCR Issues 'Dear Colleagues' Letter Regarding AI in Medicine

- 4Corporate Litigator Joins BakerHostetler From Fish & Richardson

- 5E-Discovery Provider Casepoint Merges With Government Software Company OPEXUS

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250