Is Your Associate Training Program One-Size-Fits-All?

One of the biggest challenges that law firms face in designing effective associate training programs is that the title “associate” covers such a wide swath.

February 26, 2019 at 03:44 PM

8 minute read

(Photo: Shutterstock)

(Photo: Shutterstock)

Most law firms invest significant resources into associate training. But is it working? If your law firm conducts training for associates, do you have mechanisms in place to measure success?

Those are questions that only a law firm, its associate trainees, and, I suppose, clients who ultimately use the associates can answer, but in my experiences working as an attorney—and now a trainer and coach—many training programs lack the strategic planning and rigor necessary to achieve high-impact growth and sustainability.

One of the biggest challenges that law firms face in designing effective associate training programs is that the title “associate” covers such a wide swath. A second-year associate's skill set and experience are dramatically different from that of a sixth-year associate. Therefore, a one-size-fits-all associate training program—designed for an “average” associate—will by definition lack relevance and specificity for almost everyone. An effective training program will take into account where associates are in their careers and will be structured so as to guide smaller groups of similarly situated associates to their next level of performance.

The Four Stages of Competence

In psychology, the “four stages of competence” concept is used to describe the psychological states involved when someone is progressing through the stages of learning and ultimately mastering a skill. The four stages include: unconscious incompetence; conscious incompetence; conscious competence; and unconscious competence. This heuristic provides a helpful framework for law firms looking to design a tailored associate training experience.

Unconscious incompetence (you don't know what you don't know). Most first- and second-year associates are merely trying to keep their heads above water. The stark transition from law school to law firm is a stressful one. By throwing too much at young lawyers or focusing on the wrong priorities, firms will overwhelm them. Training programs at this level should prioritize issues such as internal systems (such as technology, billing, risk management), organization skills and productivity, and fundamental technical skills (such as legal writing).

Consciously incompetent (you know what you don't know). Third- and fourth-year associates have gained firm footing. They can start to see the big picture and have a better understanding of what it takes to become a successful lawyer. They know what they don't know, and are ready to take on more rigorous training, such as advanced technical skills and learning the principles of business development in order to start laying a foundation for future business development success.

Consciously incompetent (you know what you don't know). Third- and fourth-year associates have gained firm footing. They can start to see the big picture and have a better understanding of what it takes to become a successful lawyer. They know what they don't know, and are ready to take on more rigorous training, such as advanced technical skills and learning the principles of business development in order to start laying a foundation for future business development success.

Consciously competent (you know but you're still grinding). Most fifth- and sixth-year associates have logged 2,000 billable hours or more each year, so they've hit the “10,000 Hour Rule” milestone required to achieve a high level of competence at the practice of law. They're ready for highly advanced technical skill training, including trial training, and should be expected to not only learn business development skills but also how to put them into practice.

Unconsciously competent (you know and it's starting to feel effortless). For seventh- or eighth-year associates, the practice of law should start to become routine. They should have sound judgment. Answering questions and determining a course of action in their core practice area should be second nature. They're ready to be evaluated for partnership, which means they need to start demonstrating the ability to generate business for themselves and others within the firm. Training should support those objectives.

Before we go further, a quick aside to the young lawyers reading this. Please don't get derailed by the term “incompetence.” It's not a pejorative, at least as used in this context. It's merely shorthand for describing someone who has something to learn. And, of course, we all have something to learn. In fact, having the humility to recognize one's own incompetence is the superpower that leads to success.

Think about it this way: You didn't know how to ride a bike before you practiced. You were not smarter the day you walked into law school than the day you left. The most senior, successful lawyers in your firm are incompetent in a whole range of areas. Just ask them—the odds are they're self aware enough to distinguish between, and confident enough to acknowledge, their strengths and weaknesses.

By identifying your shortcomings, and accepting that you have something (indeed, many things) to learn, you can get better. It's the only way to level up. Believing that you know everything is a recipe for standing still.

Avoid the “Forgetting Curve”

Law firm training programs fail for a number of reasons. A consistent culprit is the “one and done” cadence of training initiatives. Many take place at structured retreats where a series of talking heads take the stage to impart information to associates.

Then everyone disperses back to their offices and goes back to the way things have always been done.

Studies, and common sense, suggest that people retain information far better when it's imparted as part of something they experience. Called the “Forgetting Curve,” it's the fact that we tend to forget what we read and hear as opposed to what we experience.

The statistics that are most frequently cited online (dubious, I know, but this is an opinion column not a legal brief!) suggest that people only remember 10 percent of what they hear and 20 percent of what they read, but about 80 percent of what they see and do.

The thrust of this assertion rings true. But let's put it to a test. If I was to ask you what it feels like to have the flu, would you draw upon your own past experience of being sick or a description of symptoms from something you read on WebMD.com?

The point is, if we want associates to learn the skills necessary to grow and thrive as a lawyer, we have two choices: trial by fire or more immersive and experiential training. The right answer probably ignores the binary nature of the question—it's a bit of both—but the point is that training is too often akin to a classroom lecture and not a real world experience.

Spiraling Up to Success

So what does a successful training program look like?

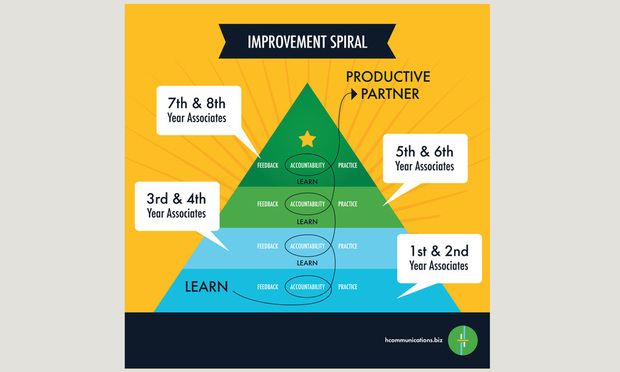

First, as discussed above, it meets associates where they are and takes into account the four stages of competence. A single training program is not for everyone. It's tailored based upon the experience levels of different associates.

Second, it's experiential. Associates should learn through doing, but in a safe, structured, rigorous environment. It involves elements of learning, but also experiential practice of the skills and techniques acquired through learning.

Third, it incorporates feedback mechanisms. There's a reason the best athletes (and the best business executives) have coaches—they need a sounding board and independent source of advice. Associates need evaluation and constructive criticism in order to level up.

Fourth, it's wrapped in accountability. In the whirlwind of activity in a law firm, most associates will push aside learning, practice, and the acquisition of new skills for the urgent demands of the moment, which are unceasing. If a law firm considers training a priority, it must hold its associates accountable to do the work.

A structured cycle of learning, practice, and feedback—all wrapped in accountability—will help associates ascend in an upward spiral of growth and improvement. This process, which I call the “Improvement Spiral,” moves associates toward unconscious competence, which will result in huge benefits for both the firm and individual lawyer.

Designing a training program that achieves real results is hard work. It requires strategic thinking and a big commitment of time and resources by a law firm. Yes, there's a cost to training a group of associates to high levels of performance. But what's the cost of the alternative?

Source: Harrington Communications.

Source: Harrington Communications.Designing a training program that achieves real results is hard work. It requires strategic thinking and a big commitment of time and resources by a law firm. Yes, there's a cost to training a group of associates to high levels of performance.

But what's the cost of the alternative?

Jay Harrington is an executive coach and trainer for lawyers and law firms and is the author of the new book, “The Essential Associate: Step Up, Stand Out, and Rise to the Top as a Young Lawyer.” He is the owner of Harrington Communications and is associated with Simier Partners. Contact him at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'If the Job Is Better, You Get Better': Chief District Judge Discusses Overcoming Negative Perceptions During Q&A

'A Template' for Religious Accommodation: Attorney Gives Insight to $12M Win Over Employer's COVID-19 Vaccination Policies

Georgia RICO Case Against Trump Likely to Avoid Trial Amid Election Win, Nationally-Known Law Professor Says

Trending Stories

- 1'A Death Sentence for TikTok'?: Litigators and Experts Weigh Impact of Potential Ban on Creators and Data Privacy

- 2Bribery Case Against Former Lt. Gov. Brian Benjamin Is Dropped

- 3‘Extremely Disturbing’: AI Firms Face Class Action by ‘Taskers’ Exposed to Traumatic Content

- 4State Appeals Court Revives BraunHagey Lawsuit Alleging $4.2M Unlawful Wire to China

- 5Invoking Trump, AG Bonta Reminds Lawyers of Duties to Noncitizens in Plea Dealing

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250