The UK Gender Pay Gap 2018: What Do The Numbers Actually Tell Us?

The second round of reporting is now over. Firms seemed to have made little progress but do the figures paint an accurate picture or could they be telling us so much more?

May 01, 2019 at 04:32 AM

9 minute read

The 5th of April is now firmly etched into the calendars of law firms across the UK. The day marks the deadline in which UK firms must report specific figures about their gender pay gap. The dust has now settled on the second round of reporting and firms can take a sigh of relief – for another year at least. Although limited solely to the UK, the figures provide a glimpse of how some of the biggest global firms are positioned in terms of their ongoing approach to gender diversity.

Of course, the obligation is not just limited to law firms but encapsulates any UK business of 250 employees or more. Last year, was the first time in which organisations were required to disclose their pay gap and although a level of imbalance was expected, the sheer magnitude in the gap took most by surprise. The legal sector was not immune. The industry also attracted added criticism over its lack of transparency with the majority of firms opting against including partners in their reporting. However, this year marked a change with 45 of the UK Top 50 providing this figure and in doing so, offering rare insight into the wide disparity in pay amongst the UK's most senior and well-paid lawyers.

In this analysis, it is argued that while a clear a gap in partner pay exists, firms should not lose sight for progress to be made in a number of aspects of gender diversity, not just in equalising remuneration. Also examined is firm performance at an employee-level which although at first glance appears to make for little progress, actually is not a fair reflection of where firms are currently at due to the inherent limitations of the reporting requirements.

Partner overview

Forty-five of the UK's top 50 firms opted to disclose their partner pay gap this year. This followed criticism last year from the UK Government's Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee that firms had something to hide by not disclosing the figure. It also formed part of industry-wide efforts to create a transparent and standardised approach around the issue of gender pay. Across the 45 firms, the average partner pay gap amounted to 16.8 percent with a median of 21.1 percent (based on figures for the 12 months to the end of April, 2018). Only three firms (Bird & Bird, Hogan Lovells and Watson Farley & Williams) boasted a pay gap in favour of all female partners demonstrating the long road ahead for the legal industry in equalizing pay at partner-level.

However, any form of purposeful shift is unlikely to take place any time soon given the deep-rooted male-centric partnerships that have become customary within the profession. The primary mechanism firms should be using to narrow the partner pay gap is to deal with the issue at source by increasing the proportion of female lawyers within their partnerships. Even here firms continue to perform badly with females consistently underrepresented at each promotions round despite ongoing pledges amongst firms to reverse this trend. Firms often speak about 'targets' and 'aims' for the future, but these do not deal with the issue of improving female representation in the now. The dominance of men within the upper-echelons of firms continues to be a cause of concern which needs to be addressed sooner rather than later or firms risk missing out on female leaders of the future.

Until women feature more predominantly at partner-level narrowing the pay gap to any form of meaningful level is set for a prolonged and arduous battle. However, it's important not to place to greater emphasis on remuneration as it has the constraint of assuming that the size of a pay-packet is the be-all and end-all for not only the entirety of female partners, but female lawyers across the board. This simply isn't the case. By focusing too readily on remuneration as the underlying cause of gender inequality distracts from the more probable causes stemming from lack of opportunities and initiatives. While a firm can look to make as much inroad as it wants in terms of equalizing pay this means little to those women which place greater emphasis upon a firm's diversity offerings including agile-working, career breaks and effective return to work programmes.

This stresses the importance for progress to be made in a number of aspects of gender diversity, not just in remuneration. The need for meaningful progress cannot be underestimated. A firm's slow rate progress simply may not be good enough for some female partners who might decide to up sticks and move to those firms seen to be making greater inroads. Furthermore, the importance of progress can be demonstrated by the emphasis placed on diversity by clients. Diversity is now integral to General Counsel (GC) selection criteria with gender forming the cornerstone of this. A firm that can demonstrate progress indicates to a GC that the firm is responsive, forward-looking and progressive.

Employee overview

As per the previous year, all UK top 50 firms were once again required to disclosure their employee gender pay gap. This excludes partners but incorporates all legal staff including business services and non-lawyer partners. Across the UK top 50, the average 2018 pay gap for employees stood at 19.5 per cent, down by just 0.2 per cent from the previous year, while the median pay gap dropped by 0.4 per cent to 27.1 per cent. At first glance, you would be forgiven in thinking that these figures look uninspiring. It seems that firms have not used the lessons learnt from the first round of reporting which highlighted such an obvious disparity to at least make some sort of progress towards narrowing the gap. But is this actually a fair reflection of the lack of progress or is it alternatively a reflection of the inherent limitations of the reporting system itself?

The reasons given by firms for the wide gender pay gap is the high female occupation of secretarial and other support roles, which also tend to be the lower paid roles in firms. As a result, a firm's employee pay gap is always likely to favour men. This suggests that the reporting requirements simply do not go far enough in determining the true extent of disparity. Take the performance of US firms for example. An initial analysis would place these firms amongst the worst offenders at the employee-level. But how can a meaningful conclusion be drawn from an average figure that combines the salary of a female secretary to that of a male associate on an eye-watering City salary? Even the breakdown of employee pay quartiles should be viewed with scepticism as we still don't know the rates of pay for comparable jobs or different patterns of working. A much more accurate picture can be made when like-for-like is compared.

In other words, the gender pay gap reporting could be telling us so much more. This is particularly in the case of non-lawyer partners. From their perspective, the primary reason for wanting to examine a firm's gender pay gap performance is for career planning. However, to form an opinion based on the current reporting requirements would be misguided. What's required is for more firms to breakdown their employee pay gap into specific job roles. This could include directly comparing the disparity in pay between female and male associates. Although some firms provide this figure, take-up across the board is generally negligible. But even this may still not be enough for some. Ideally, firms should be going one step further and providing a breakdown of their gender pay at each step of the career ladder. This would involve disclosing the disparity in pay at different levels of PQE which would create a far higher-level of transparency in which informed decisions can be made.

Identifying the cause of inequality

The legal industry continues in its struggle to shake off its macho image which has forever blighted the profession and acted as an impediment to progression. Of course, the legal industry is far from alone, but it is nonetheless guilty of consistently demonstrating an unwillingness to innovate and more with the times which has left other industries trailing in its wake. These foundations were set in stone long ago but it is the profession's inability to alter these foundations which has led to the issue of gender inequality now coming to a head.

The gender pay gap is only one mechanism that has been used to expose this. However, the reporting requirements in addition to possessing the limitations discussed above, also suffer from the insurmountable obstacle of not identifying the underlying cause of inequality. The numbers don't tell us whether the inequality is caused by discrimination or whether it has its origins in the differing choices made by men and women. Only firms can truly grapple with this and only firms can act upon the root cause to remedy the situation.

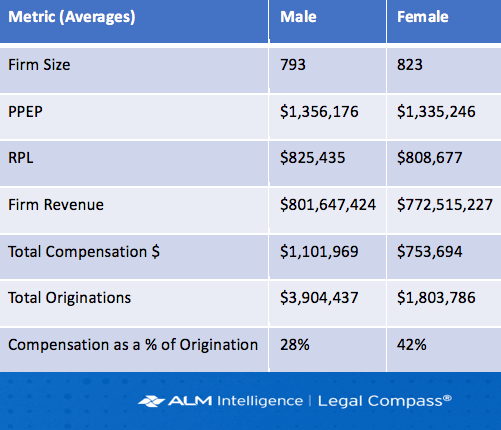

U.S. firms have faced similar struggles. In 2018, ALM Legal Intelligence surveyed Am Law 200 partners, and found that on average, with all other metrics relatively equal, female partners earned 68 percent of what their male counterparts did, as shown in the chart above. While programs like The Mansfield Rule are helping to address gender disparities in firms, firms and attorneys can see for themselves that there are still sizable differences in compensation.

Of course, not all firms are the same regardless of their geographic location. Many have made promising inroads and demonstrated a willingness to change. These are the firms currently ahead of the curve. However, firms should not be developing programmes and initiatives for the sake of it. A programme means nothing if it doesn't generate positive outcomes. It's also important for firms to demonstrate clarity. A lack of lucidity on what a firm's position on gender diversity actually is simply isn't good enough as part of a modern-day legal profession if the firm wants to be an attractive proposition for female lawyers.

Across the legal industry as a whole, there is a long road ahead requiring unity and acceptable across the profession in order for meaningful progress to be made. Ultimately it's easy for firms to talk a good game but a lack of purposeful action in improving gender diversity will eventually catch up with them. It's these firms that risk being alienated by clients and losing out on female talent.

Click here for a full table of the gender pay gap figures across the UK Top 50

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

ALM Market Analysis Report Series: Nashville's Rapid Growth Brings Increased Competition for Law Firms

Trending Stories

- 1The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 2Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 3Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 4Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

- 5Zoom Faces Intellectual Property Suit Over AI-Based Augmented Video Conferencing

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250