Mass Tort Attorneys: Judges Want to Know About Your Outside Financing

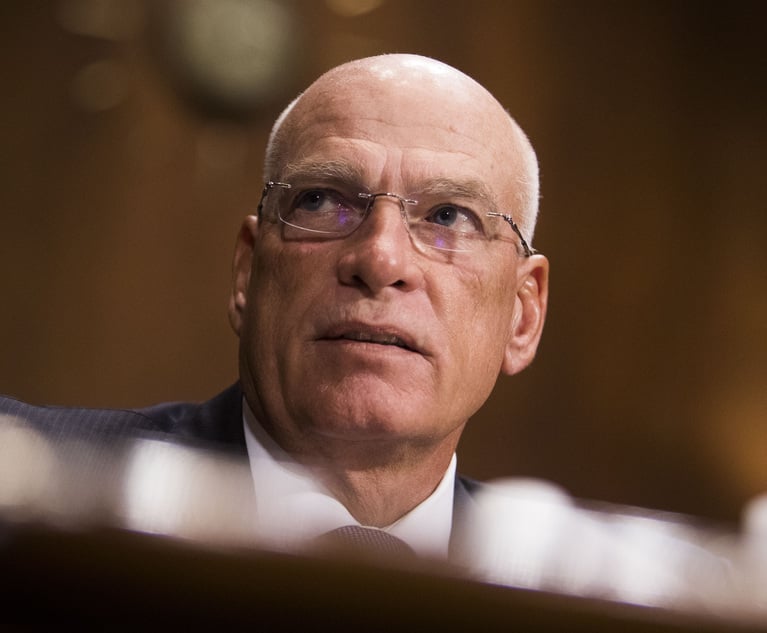

At least three federal judges in multidistrict litigation have asked plaintiffs lawyers to disclose third-party litigation funding. “The minute you have an involvement of someone else," U.S. District Judge Paul Grimm, in the Marriott data breach cases, told Law.com, "you have the benefit of funding, but with that funding, there is a question about is there to be control or not.”

May 02, 2019 at 08:12 PM

8 minute read

As rule makers and politicians continue to debate about whether to disclose third-party funding in multidistrict litigation, some federal judges have forged ahead in requiring plaintiffs lawyers to do just that.

In the past year, judges in at least three cases have ordered such disclosures, in most cases as part of the process of appointing plaintiffs attorneys to leadership teams. The three MDLs involved include some of the largest mass torts in the country.

In the most recent case, U.S. District Judge Casey Rodgers, in Pensacola, Florida, has ordered plaintiffs' lawyers to disclose by Friday how they are funding hundreds of lawsuits brought by U.S. service members over 3M's combat earplug cases. Last month, U.S. District Judge Paul Grimm, in Greenbelt, Maryland, ordered outside financing disclosures in dozens of class actions brought over Marriott's data breach.

Grimm told Law.com that it's important judges know everyone with a stake in a case.

“What you don't know, if you have third-party funding, is if someone from the outside has made a decision, an investment decision, that this case has merit, and they have advanced the money to take the case forward,” he said. “Then, when it comes time to resolve the case, those people are not in the room, and if they have minimal expectations of what they must recover in order to maximize their investment, that is an influence, a potential influence, in how the litigation is conducted and how the litigation might be resolved.”

The orders represent increasing awareness about third party financing among MDL judges, who, in the past, have focused mostly on the qualifications of lead counsel applicants.

“These orders reflect an increasing realization that third-party funding inherently raises questions that the courts need to ask, including control issues and ethics concerns, and the judges need to know who's really in the courtroom,” said Alex Dahl, general counsel of Lawyers for Civil Justice.

Lawyers for Civil Justice is among a growing group of corporate interests pushing to force disclosures of outside funding in contingency fee cases. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce's Institute for Legal Reform and other business groups have called on Congress and the Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Rules of Civil Procedure to consider a rule mandating such disclosures in class actions and multidistrict litigation. The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California in 2017 adopted a new rule in class actions, and Wisconsin's Legislature passed a law last year requiring such disclosures in state court cases.

The orders coming out of MDLs are a big boost for defendants, since most judges have been reluctant to grant disclosure requests they have made in the past. But judges aren't providing everything the defense bar has been clamoring for. Rodgers and U.S. District Judge Dan Polster, in Cleveland, who ordered plaintiffs lawyers a year ago to disclose third-party financing of cases brought by cities and counties over opioids, had the lawyers file the funding details for in camera review. Grimm's order gave lawyers the option to file them under seal, but all the applicants said in publicly filed documents that they were funding the cases on their own.

Polster's order, however, might have had some legs, said J. Maria Glover, a professor at the Georgetown University Law Center, noting that outside financiers praised the move. His order, she said, might have “set a little bit of a model for how judges might balance the needs of ensuring this adequate representation without opening the flood gates to disclosure.”

“They said, 'look, this is how disclosure ought to be,'” she said. “This is appropriately done, limited in scope, not being provided for more of the nefarious reasons we worry about. It's being provided to ensure a solid representational structure for a significant number of absent plaintiffs represented in mass tort litigation in camera.”

In an emailed statement, Burford Capital CEO Christopher Bogart said the recent disclosure orders in MDLs are more reasons why a mandatory rule was unnecessary and “overly burdensome.”

Grimm's order, like Polster's, “let counsel affirm upfront that funders are taking no control and did not inquire about the terms of funding,” he wrote. “He allowed counsel to respond under seal or ex parte, recognizing that a law firm's finances are nobody else's business—and indeed the financing section was the only section of the order that received this special treatment.”

Both Rodgers and Polster declined to comment for this story.

|What Are Judges Looking For?

The motivations behind such orders aren't entirely clear. Judges might simply want to know whether plaintiffs attorneys have enough money to fund the entire MDL, said Glover. But there could be more to it than that. Both Polster and Grimm had specifically asked what strategic role an outside funder, if there were one, would have over the lawyers.

“Because there is such an ongoing ethical debate about the level of control that the funders do or do not exercise, there's been a question as to whether, especially in the mass litigation context, we ought to be extra vigilant,” Glover said. “To the extent judges are asking to see information about the funding, it is possible that they are also looking into those ethical issues.”

Grimm said he had such concerns. Money influences how the plaintiffs law firms that fund their own cases choose their experts, or frame their legal arguments, for instance, but it also puts them at a litigation risk.

“You can understand that impulse and that desire to be sort of free from that,” he said. “The minute you have an involvement of someone else, who provides that, you have the benefit of funding, but with that funding, there is a question about is there to be control or not.”

Just how much control? He posited that an outside funder could decide whether to file a motion, how much to spend on experts, and how to handle settlement discussions, for instance.

Grimm, who spent six years as a member of the Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Rules of Civil Procedure, said he had not been following the group's more recent deliberations about proposals to mandate disclosure of outside funding in MDLs. But he is aware of how outside financiers are changing litigation and has looked to the MDL guidelines published by Duke University School of Law's Bolch Judicial Institute and the Federal Judicial Center's Manual for Complex Litigation, as well as suggestions from the U.S. Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation on how to select lawyers for leadership positions.

“One of the things the guidelines suggest is to pay careful attention to how the funding will happen,” he said. Not only does that influence lead counsel's strategic decisions, he said, but whether they ask for financial contributions from lawyers who are not in such roles.

He also said his concerns date back to his work as a federal magistrate judge for 16 years before President Barack Obama appointed him as a district judge seven years ago. He estimated he oversaw between 1,000 to 2,000 settlement conferences as a magistrate judge.

“We knew in order to have a greater chance of settlement, you need someone in the room with the ability to make a decision,” he said. “When we just had the lawyers, and didn't have people with skin in the game, we found in all of the cases we couldn't make progress.”

Experts following third party financing in MDLs were hesitant to say the orders from the bench represented a trend. They might even be misguided, said Anthony Sebok, a professor at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University. He questioned, for instance, why Rodgers wanted to know the particulars of bank loans that plaintiffs' lawyers had—not just third-party litigation financing.

And he wondered whether judges were familiar with the difference between funding to clients, as opposed to lawyers.

“Client-directed is what has been happening in the vast majority of third-party financing transactions,” he said. Lawyers would not necessarily have the information the judge wants to disclose those arrangements. More importantly, orders focused on how much control a funder has over a lawyer's decisions are an “odd question to ask” because such an arrangement would be prohibited in every state and unethical, he said.

He said judges might be confusing outside litigation financing with liability insurers that defendants have had for years.

“Judges think, of course, third parties have control over settlement, because they see it every day in their courtroom with a liability insurer,” he said. “But that's not true.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Appropriate Relief'?: Google Offers Remedy Concessions in DOJ Antitrust Fight

4 minute read

'Serious Disruptions'?: Federal Courts Brace for Government Shutdown Threat

3 minute read

'Unlawful Release'?: Judge Grants Preliminary Injunction in NASCAR Antitrust Lawsuit

3 minute read

'Almost Impossible'?: Squire Challenge to Sanctions Spotlights Difficulty of Getting Off Administration's List

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1The end of the 'Rust' criminal case against Alec Baldwin may unlock a civil lawsuit

- 2Solana Labs Co-Founder Allegedly Pocketed Ex-Wife’s ‘Millions of Dollars’ of Crypto Gains

- 3What We Heard From Litigation Leaders This Year

- 4What's Next For Johnson & Johnson's Talcum Powder Litigation?

- 5The Legal's Top 5 Pennsylvania Verdicts of 2024

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250