What's Next: Facial Misidentification | Dose of Dystopia: Internet God Mode Edition

Apple is accused of using facial identification to nab the wrong guy, an issue that could raise additional issues in the wake of laws like BIPA.

May 08, 2019 at 07:30 AM

6 minute read

Welcome back for another week of What's Next, where we report on the intersection of law and technology. This week, we take a look at a lawsuit accusing Apple of using facial recognition to accuse the wrong person of shoplifting. Plus, questions are surfacing again over when the government tells companies about software exploits it's discovered. As always, thanks for reading.

➤➤ Would you like to receive What's Next as a weekly email? Sign up here.

Facing the Facts

The Illinois Supreme Court made waves earlier this year after ruling that a 14-year-old boy's rights were violated under Illinois' Biometric Information Privacy Act after Six Flags collected and stored his fingerprint for park access without prior required notice and release. Some attorneys thought the ruling might lead to a flood of biometric suits, and whether that actually comes to fruition remains to be seen. But where it might see its most immediate application is in an area of technology that a lot more companies are familiar with: facial recognition.

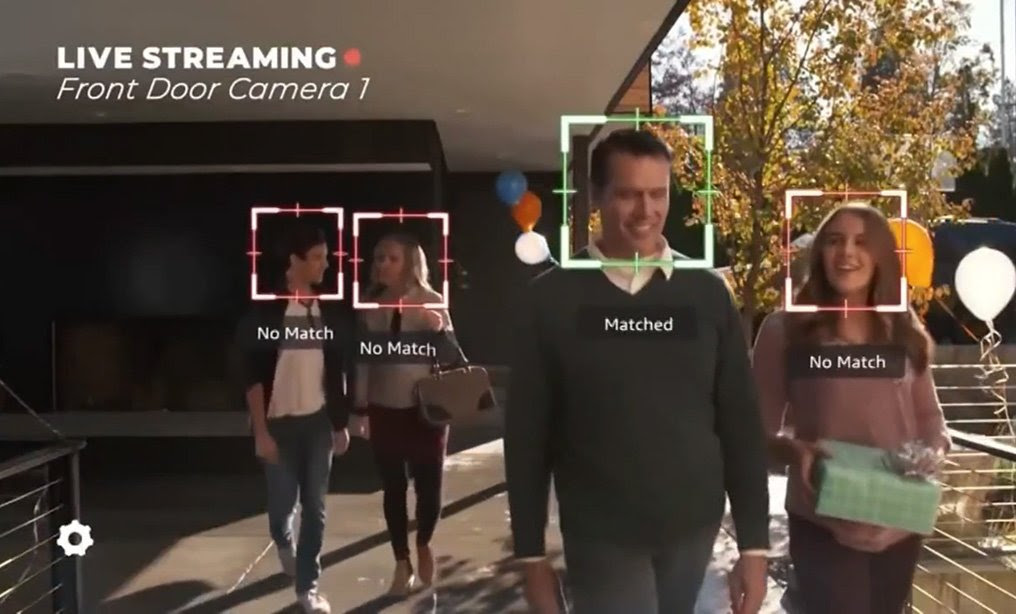

Last week, an 18-year-old New Yorker named Ousmane Bah sued Apple, alleging he was misidentified in a string of Apple store thefts. What's interesting, though, is that the suit alleges the misidentification occurred through facial recognition technology, as allegedly relayed to Bah by an NYPD officer. Apple claims it doesn't use this technology, but the mere mention of it should raise some eyebrows—especially in Illinois, where that aforementioned BIPA allows for a private cause of action for violations.

Mary Smigielski, a partner at Lewis Brisbois Bisgaard & Smith, told Legaltech News that “there's a great risk to using that technology in a state like Illinois.” The problem, she explained, is that violating the law can occur easily. “You only need a technical violation,” Smigielski said. “You don't need to have a data breach or have the information stolen, just the mere fact that you proceeded without having consent is violation.”

What it means for retailers in Illinois is that they must have that consent: Drinker Biddle & Reath partner Justin Kay suggested a readily available public policy explaining what the retailer is collecting, why it is collecting, consent to share it and “can't otherwise profit from it.” And even outside of Illinois, it may be a good idea to implement public notice of facial recognition policy where possible.

It's not just a legal issue, added Proskauer Rose partner Jeffrey Neuburger, but a public perception one: “I think it takes away some of the creepiness factor if people ultimately find out they are using facial recognition.” —Zach Warren

Dose of Dystopia: “Internet God Mode”

In the inaugural issue of this newsletter, we wrote about the “Vulnerabilities Equities Process,” an obscurely-named set of U.S. government policies and procedures that determine whether NSA hackers will tell companies about software exploits they've discovered—or keep them secret as tools to use against enemies. The key phrase there is “keep them secret.”

We already know from the “WannaCry” debacle that that doesn't always pan out as planned. Leaks by a group known as the Shadow Brokers in 2017 unleashed NSA weapons on systems around the world. Certain big tech companies (ahem, Microsoft) were none too happy to find out they had been kept in the dark. And now, on Monday, security firm Symantec revealed that the vulnerability underlying Wannacry was used in the wild even before the Shadow Brokers leak, raising new questions about the U.S. policy.

The so-called SMB vulnerability has been described as “Internet God mode,”giving an attacker access to the guts of the computer's system without the user having to click a link or do anything. Wired reporter Andy Greenberg explains the new findings in depth this week:

Symantec found that by March 2016, the SMB zero-day had been obtained by the Chinese BuckEye group, which was using it in a broad spying campaign. The BuckEye hackers seemed to have built their own hacking tool from the SMB vulnerability, and just as unexpectedly were using it on victim computers to install the same backdoor tool, called DoublePulsar, that the NSA had installed on its targets' machines. That suggests that the hackers hadn't merely chanced upon the same vulnerability in their research—what the security world calls a bug collision; they seemed to have somehow obtained parts of the NSA's toolkit.

Companies have faced legal scrutiny over shoddy device security. Surely, the types of advanced exploits in the hands of the NSA are of a different variety. Still, against that backdrop, this episode seems to present thorny questions of liability. If the computer systems of a bank—or a hospital—get severely compromised by a hack, what responsibility should the maker of the software hold? And how should that equation change if the government was holding the secret keys all along? —Ben Hancock

On the Radar:

Tweet Screening: Elon Musk's latest agreement with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission requires the chief executive officer get preapproval from securities counsel before tweeting about Tesla finances, but it's not yet clear who that lawyer is or if he or she has been selected. The agreement resolves SEC allegations that Musk breached an October 2018 settlement with the agency in February by tweeting inaccurate 2019 Tesla sales production estimates without running the post past his general counsel. Read more from Caroline Spiezio here.

Follow the Money: As rule makers and politicians continue to debate about whether to disclose third-party funding in multidistrict litigation, some federal judges have forged ahead in requiring plaintiffs lawyers to do just that. Judges in at least three cases have ordered such disclosures in the past year, in most cases as part of the process of appointing plaintiffs attorneys to leadership teams. Read more from Amanda Bronstad here.

Corporate Blockchain: Maryland now allows corporations to keep their records and transmit corporation communications through blockchain. Its Big Law drafter said the amendments should allow for quicker transactions and shareholder communication. Read more from Victoria Hudgins here.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

What's Next: Judge to Quash Twitter Subpoena | SCOTUS Won't Review Trial Ban

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1The Rise and Risks of Merchant Cash Advance Debt Relief Companies

- 2Ill. Class Action Claims Cannabis Companies Sell Products with Excessive THC Content

- 3Suboxone MDL Mostly Survives Initial Preemption Challenge

- 4Paul Hastings Hires Music Industry Practice Chair From Willkie in Los Angeles

- 5Global Software Firm Trying to Jump-Start Growth Hands CLO Post to 3-Time Legal Chief

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250