ABA's Tougher Bar Pass Rule for Law Schools Applauded, Derided

The American Bar Association's new standard could increase pressure on jurisdictions like California with high cut scores to lower that threshold. It could also add momentum to the burgeoning movement to overhaul the bar exam itself.

May 21, 2019 at 01:57 PM

7 minute read

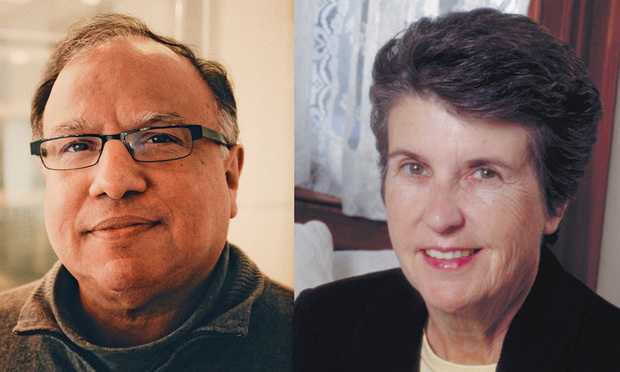

Daniel Rodriguez and Susan Prager. Courtesy photos

Daniel Rodriguez and Susan Prager. Courtesy photos

Three days after the American Bar Association decided to toughen the bar passage standard for law school accreditation, legal educators have sharply diverging views on what the new rule will mean and how things might change—or not.

The Council of the Section of Legal Education on May 17 adopted a long-debated rule change that reduces the time—from five years to two years—that schools have to get at least 75 percent of their graduates to pass the bar exam.

Proponents say the ABA rightly has cracked down on underperforming campuses, while opponents argue that the change will exacerbate the uneven playing field between schools in different jurisdictions and imperil diversity efforts.

What's clear, however, is that the ABA was responding to the growing pressure for law schools to graduate students who can pass the all-important test, given the record number of exam failures in recent years.

Some educators, like Southern University Law Center chancellor John Pierre who has been a vocal opponent of the new rule, warned that giving schools just two years to ensure three-quarters of graduates pass instead of five years is a major change that could have unintended consequences such as reducing the pipeline of minority lawyers into the legal profession.

Others, including Pepperdine University law professor Derek Muller, predict that some lower-performing schools will make adjustments to try and up their bar passage rates but that the new standard won't spur a sea change throughout legal education.

“I won't expect anything too dire,” Muller wrote on his blog, Excess of Democracy. “While it's safe to say that 30 or so law schools have something to worry about, a much smaller number are facing existential threats to their schools.”

Attorney and legal education pundit David Frakt reached a similar conclusion in a post on The Faculty Lounge, concluding that the vast majority of schools will be able to meet the new rule and that it will be a catalyst to improve admissions practices among schools in danger of missing the cut.

“Replacing the toothless prior [bar pass standard] with the new [standard] should help reduce the exploitation of unqualified students of all races. That makes today a great day for legal education,” Frakt wrote.

The heat of the debate over the bar pass standard has cooled significantly in recent months as many opponents anticipated that the council would move forward with a tougher standard that was twice rejected by the ABA's House of Delegates.

“I think people had already said what they were going to say about it,” said Law School Admission Council president Kellye Testy, noting that few people attended the council's May 17 meeting in Chicago or submitted new letters in support or opposition of the change.

In addition to reducing the compliance time to two years for 75% of their graduates to pass the bar, the new standard eliminates a provision that permitted schools to meet the standard by having a first-time bar pass rate within 15% of the average within their jurisdictions. Also under the old rule, schools were required to report bar outcomes for only 70% of each graduating class.

The new rule eliminates the first-time pass rate provision and requires schools to report outcomes for all graduates. If schools miss the 75% pass rate cut, they could lose their ABA accreditation.

Recent bar exam data from the ABA showed that 23 schools would have failed to meet the new standard based on results from the class of 2016.

“I applaud the ABA for pushing ahead with this reform,” said Dan Rodriguez, a professor at Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law and an early proponent of the change. “I know and appreciate the concerns expressed by various stakeholders, including deans, about the impact of this decision on low-performing law schools. However, this proposal has been bouncing around for nearly three years, and we haven't seen much by way of alternative strategies to respond constructively to what we can all agree is a problem—significant bar failure rates and the corresponding financial and psychic costs to graduates.”

Judith Gundersen, president of the National Conference of Bar Examiners, also welcomed the tougher standard.

“[The National Conference] supports the revision to [the bar pass standard] for its clarity for would-be law students, most of whom attend law school with the goal of becoming a practicing attorney, so bar passage is an end goal,” Gundersen said. “How a law school's graduates fare on the bar exam in their respective markets is relevant information for prospective students.”

But Southwestern Law School Dean Susan Westerberg Prager countered that the failure of the new standard to account for different exam cut scores across the country disadvantages schools in jurisdictions such as California that have relatively high thresholds.

“Even those of us in California who will meet the new standard, as Southwestern will, suffer negative effects, because the national comparisons published by the ABA and used in rankings paint a misleading picture,” she said. “Of course people will assume that schools in states with low pass rates are 'less good' than schools which are in reality weaker but are located in states with high or higher bar pass rates.”

William Wesley Patton, a lecturer at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law whose analysis of the bar pass data concluded that the 49 schools at risk of missing the new standard enroll 37% and 35% of the nation's African American and Hispanic law students, said the ABA council could have other goals in mind.

“Either the ABA Council simply ignored the clear empirical evidence that the new bar standard will decrease diversity in the bar, or it passed the new standard with the hope that states, like California, that have unreasonably high bar cut scores will lower those metrics in order to ameliorate the council's action,” Patton said.

Added pressure on jurisdictions with high bar exam cut scores to lower them is one possible outcome of the new rule, several observers said. California, which has the highest cut score in the country at 144, likely will not want to see the ABA accreditation of some of its longstanding schools threatened, they said.

It remains to be seen how schools that are at risk under the new rule will adjust, though there are numerous predictions. Among them:

- They will tighten their admissions standards to reduce the number of new students likely to struggle on the bar.

- They will academically dismiss a larger portion of first-year students.

- They will invest further in academic support and bar preparation courses.

The rule change may also place more focus on the bar exam itself and whether it's the best way to gauge lawyer competency, said Testy and Rodriguez. The National Conference of Bar Examiners has convened a task force examining all aspects of the test and the new standard could prompt more people to engage in that effort, Testy said.

Rodriguez said the new standard could prove a catalyst for major reforms in reconciling uneven cut scores across jurisdictions as well as modernizing the exam's “anachronistic approach to measuring lawyer competencies.”

“Increasing accountability through a higher bar passage standard is not the end of the road, but is just one part of a dynamic process which has at its end not punishment of law schools, but creative reform of our credentialing and education system,” he said. “We were moving much too slowly in this direction under the status quo. Perhaps we will move with more urgency and resolve now.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

University of Chicago Accused of Evicting Student for Attending Gaza-Israel Protest

3 minute read

Sanctioned Penn Law Professor Amy Wax Sues University, Alleging Discrimination

5 minute read

The Met Hires GC of Elite University as Next Legal Chief

Trending Stories

- 1Pro Hac Vice in Georgia: Rule Change for Nonresident Attorneys

- 2The Benefits of E-Filing for Affordable, Effortless and Equal Access to Justice

- 3AI and Social Media Fakes: Are You Protecting Your Brand?

- 4A Primer on Using Third-Party Depositions To Prove Your Case at Trial

- 5‘Catholic Charities v. Wisconsin Labor and Industry Review Commission’: Another Consequence of 'Hobby Lobby'?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250