Q&A: Senator Who Beat Roy Moore Pens Book on Prosecuting Birmingham Church Bombing

Doug Jones, a former assistant U.S. attorney, brought the case against two Klansmen convicted in the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed four African American girls ages 11 to 14.

May 21, 2019 at 11:41 AM

6 minute read

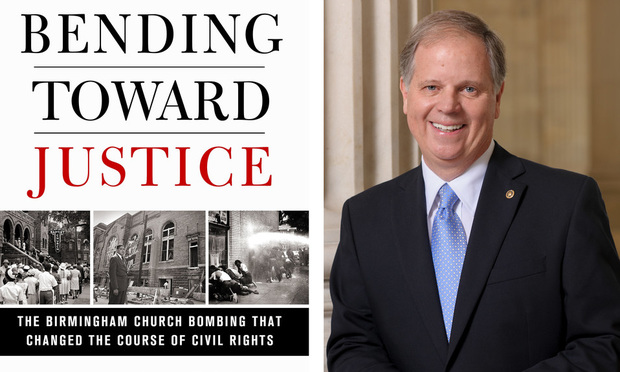

Sen. Doug Jones, D-Alabama, and his new book, “Bending Toward Justice.” (Courtesy photos)

Sen. Doug Jones, D-Alabama, and his new book, “Bending Toward Justice.” (Courtesy photos)

“You are absolutely right about that,” Doug Jones told me, letting out a guffaw. “That's the secret that I try to keep buried.”

The trial lawyer-turned-recently elected U.S. senator from Alabama confirmed that I'd figured out his favorite thing about being a member of the so-called world's most exclusive club—no time sheets.

Jones, a Democrat, won his Senate seat in late 2017, in a special election to fill the vacancy when Jeff Sessions was tapped by President Donald Trump to serve as his attorney general. Jones, who had been a white-collar defense partner at Birmingham's Jones & Hawley before the election, defeated Republican Roy Moore, the state's former chief justice, who had been expelled from the bench for defying a court order to remove a large statue of the Ten Commandments from the courthouse. During Moore's Senate campaign, nine women accused him of inappropriate conduct.

While my phone conversation with Jones, 65, was filled with lighthearted moments, the topic on the table was anything but. Jones called me from the nation's capital to discuss the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham that killed four African American girls ages 11 to 14. Jones, as a U.S. attorney, successfully prosecuted two of the Klansman-bombers in 2001 and 2002. The bombing, and the hows and whys it took nearly four decades to get the convictions, is the subject of Jones's recently published book—“Bending Toward Justice” (All Points Books, co-authored with Greg Truman).

The cover of “Bending Toward Justice” states that the Birmingham church bombing “changed the course of civil rights.” I asked Jones why this tragedy has such prominence in the fight for equality.

Jones ticked off several pivotal events in the civil rights movement that preceded the bombing, including Brown v. Board of Education, the Montgomery bus boycott, the murder of Emmett Till and the children's marches in Birmingham. The momentum was building, he pointed out. “But when all of a sudden, four innocent children were killed in a house of God on a Sunday morning,” he said, “that pulled them all together.” Now “this is not just about equality, it's about life and death.”

Jones explained that the church bombing “galvanized all of those into one force that really helped wake up people to the sins of Jim Crow in the South and other places.”

Two months later, President Kennedy was killed and then “everything just seemed to get accelerated at that point. The Civil Rights Act was passed in '64 and the Voting Rights Act passed in '65.”

The Birmingham church bombing was part of Jones's fabric long before he sent two of the bombers to prison. The first trial of a bomber took place in 1977. Bill Baxley, Alabama's attorney general, won a murder conviction of Robert Chambliss.

In an eerie foreshadowing, Jones watched the trial while a law student at the Cumberland School of Law at Samford University in Birmingham and was in the courtroom when the verdict was read. He left knowing that his future “career as a lawyer would always be grounded in some way by that case.”

Jones owed his presence at the Chambliss trial to U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas. Jones, while a student at the University of Alabama, had the chance to meet Douglas. The aspiring trial lawyer asked the legendary jurist for career advice. Watch good lawyers ply their trade, Douglas told him. Jones did, often, he told me.

Jones left Cumberland and, in another foreshadowing, went to work for Alabama Sen. Howell Heflin, whose seat Jones would later occupy. From there he embarked on a career as an assistant U.S. attorney and then private practice.

Jones' opportunity to finish the job that Baxley started came in 1997 when he was nominated by President Bill Clinton to serve as U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Alabama. At the time, the bombing had been the subject of the office's investigation. Jones was now in the right place, at the right time, to handle the case that he said had “influenced [his] whole life.”

“Bending Toward Justice” is the story of both Baxley's and Jones' prosecutions. But these were not whodunnits. The prime suspects—members of a Ku Klux Klan fringe group that advocated even more violence than the national organization—were identified not long after the bombing, thanks to polygraph tests, witness statements and the suspects' shaky alibis. The real stories Jones tells are why the suspects were not charged at the time and the challenges of finally prosecuting them so many years later.

Here, Jones, by examining the bombing in the context of the era, paints a picture of his segregated home state that made prosecutions not possible. During the mid-60s, Jones said, even with concrete evidence and multiple eyewitness accounts, “conviction of white men in the South by all-white, all-male juries was the exception rather than the rule.”

When the times were finally right to bring the cases—especially for Jones, nearly four decades later—the long delays presented huge evidentiary and other prosecution challenges. Even witnesses who had not died were, in some cases, too infirm to testify or needed medical escorts to do so. Jones lays out these prosecution difficulties in a way that both lay readers and lawyers will appreciate.

While Jones was only 9 years old at the time of the church bombing, “Bending Toward Justice” is a riveting insider's account. He tells the story as a lawyer—focusing on such things as rules, evidence and burden of proof—as well as historian and Alabamian who is unafraid to confront the state's ugly past.

Alabama's junior senator says on the last of his 350 pages that “on several occasions over the years, I wanted intensely to put the church bombing case behind me. It dominated my life and, especially in quiet moments, its ugliness was sometimes overwhelming.” Given a possible downside of taking a legally important, but life-consuming, case, what advice would he give to a lawyer confronted with the opportunity?

“Take it. Take it,” Jones said without a moment's hesitation. “I tell lawyers and judges all the time that I really do wish that every lawyer, every judge, but particularly lawyers, who are advocates, could have and work on a case that means so much to so many people.”

He added that “it helps change you as a person. You look at the world differently. You look at people differently.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at Temple University Beasley School of Law.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

How I Made Partner: 'Focus on Being the Best Advocate for Clients,' Says Lauren Reichardt of Cooley

How I Made Practice Group Leader: 'It’s a Job About People, First and Foremost,' Says Alexander Lees of Milbank

Quiet Retirement Meets Resounding Win: Quinn Emanuel Name Partner Kathleen Sullivan's Vimeo Victory

Trending Stories

- 1Five Years After Vega Much Remains Unsettled in Pay Frequency Litigation

- 2DLA Piper Hires Former FAA Chief Counsel as Transportation Practice Co-Chair

- 3Firms Come Out of the Gate With High-Profile Litigation Hires in 2025

- 4Legal Departments, Firms Expect Gen AI to Boost ALSP Usage

- 5Law Firms Are 'Struggling' With Partner Pay Segmentation, as Top Rainmakers Bring In More Revenue

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250