'Destroying Segregation': Q&A with Fred Gray, Lawyer for Rosa Parks and MLK Jr.

For Fred Gray, practicing law has been a long journey. “A bus can take you from where you are, to where you want to go.”

June 24, 2019 at 03:05 PM

8 minute read

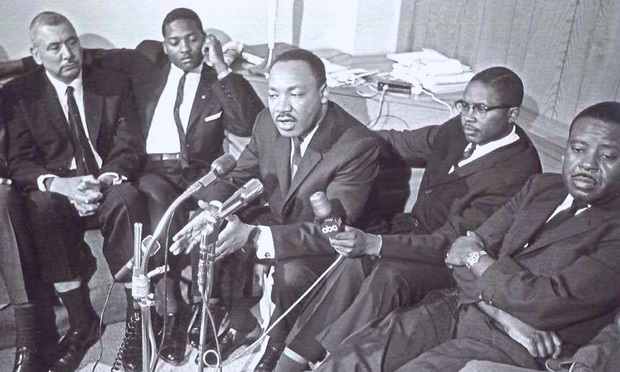

L-R: H.O. “Red” Williams, Lucius D. Amerson, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Fred Gray, Ralph Abernathy, in 1966, after passage of the Voting Rights Bill of 1965.

L-R: H.O. “Red” Williams, Lucius D. Amerson, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Fred Gray, Ralph Abernathy, in 1966, after passage of the Voting Rights Bill of 1965.

“Destroy everything segregated I could find.” This, Fred Gray told me, was the reason he went to law school. Gray wasted no time. In 1955—remarkably, just one year out—he represented Rosa Parks, on trial for her legendary act of defiance on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

Parks was found guilty. But Gray got the last word. Less than one year later, he convinced the U.S. Supreme Court to declare racial segregation of Montgomery's buses unconstitutional.

If Fred Gray's goal was to destroy everything segregated he could find, he was blessed with good timing. Just weeks before Gray graduated from law school, the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education, striking down the “separate but equal” doctrine in public education. Of this extraordinary alignment of the stars, Gray, also a long-time preacher, said he could not rule out “divine intervention.”

Makes sense. Around the same time, Gray had another well-known client: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Last month was the 65th anniversary of Brown. For nearly an hour, the 88-year-old Gray, by phone from his law firm's office on Fred Gray Street in Tuskegee, Alabama, shared with me a range of experiences over his lifetime as a civil rights lawyer, including building on Brown to achieve what he set out to accomplish.

Brown gave lawyers the “tools and the legal basis” to fight segregation, Gray told me. However, he was quick to add that you could not have desegregated the buses without having the Montgomery bus boycott. Gray gives all of the credit for it to the involvement of the community.

The 382-day boycott, by African Americans, of the buses in Montgomery—and considered by many scholars to be the beginning of the civil rights movement—began the day Rosa Parks was found guilty. Gray “vigorously defended” her, he said. But his constitutional challenges were summarily denied, and it was all over in 30 minutes.

The boycott finally ended in conjunction with Gray's 1956 victory in Browder v. Gayle, where the Supreme Court held that segregation of the races, on Montgomery's buses, violated the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses of the Constitution.

“The real issue that we get from the bus boycott,” Gray said, “is the fact that other people realized, if we could see what they did there, use that, add something else to it, and we'll be able to solve our problems, whatever they are, where people are being mistreated and being denied their constitutional rights.”

Gray knows of what he speaks when he told me that a judicial decision alone could not have ended segregation. Gray desegregated his own elementary school in Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education. In this 1964 Alabama federal court opinion, the court observed that, although it had been 10 years since Brown, the Montgomery Board of Education had done virtually nothing to comply with it.

On account of Rosa Parks, and what followed in Montgomery, buses have long had a powerful association with the civil rights movement. For Gray, this public transportation was also life altering. He originally set out to be both a preacher and a teacher, calling these two professions the only options available to an African American male from the parts of Montgomery “where nothing good is supposed to come.”

Gray attended Alabama State College for Negroes to prepare for a career as an educator. But, following graduation, he abandoned those plans. “It was because of the conditions I saw in having to ride the buses,” he told me, “and seeing how people were treated, that I made the commitment that I would not only be a preacher, but I would become a lawyer. And not just a lawyer but a civil rights lawyer.”

It was then that Gray made the personal commitment to use his degree to destroy segregation. Ironically, to do so, he had to be victimized in the process. Because the University of Alabama Law School did not accept African Americans, Gray attended Western Reserve University School of Law in Cleveland.

It is a lawyer's job to serve his or her clients without distraction that could come from having a personal stake. For Gray, when his clients' causes were often his own, it seems to have been a challenge for him. Gray, not unmindful of my observation, told me that he “didn't take this as a personal matter.” He kept his personal feelings of why he became a lawyer separate and distinct from the issues. There was a strategic reason for such objectivity, wanting to present to the court that “it's not a personal matter but it's what the Constitution requires and it's not being followed and that's what I want to see corrected.”

Martin Luther King Jr.

In 1960, Martin Luther King Jr., then living in Atlanta, was indicted and put on trial in Alabama for perjury—a novel charge—in connection with the filing of his Alabama state tax returns. Gray called it politically motivated. “At this point [King] has become an icon and the voice of the movement,” he explained. “I think they believed that if we can get him convicted, then this will stop what he's doing.”

For King, facing a felony charge, the stakes could not have been higher. In addition to possible prison, “a conviction would have seriously weakened his credibility,” Gray said. “At the same time that he's talking about civil rights, he's cheating the state and doesn't want to pay his state income tax.” Gray, along with others, represented King, who was found not guilty by an all-white jury after a four-day trial. It was just one of several instances in which Gray served as counsel to King in connection with his civil rights activities.

In an interesting judicial confluence, the King perjury trial is directly related to New York Times v. Sullivan, the Supreme Court's landmark 1964 decision setting out the standard for a public official to bring a defamation claim. The New York Times advertisement at issue in Sullivan, that allegedly libeled a Montgomery public safety officer, had, as one of its purposes, raising funds for King's defense in his tax case. Here, too, Gray was involved—representing four ministers accused of libel in connection with the ad. They lost, until the Supreme Court had its say, following its adoption of an “actual malice” standard for a public official to bring an action for defamation.

Gray pointed to Sullivan as evidence that the civil rights movement was about more than just securing rights for African Americans. As he explained it, what it accomplished, with respect to obtaining rights under the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment, “now serves more white people than it does blacks, because there is more of them.”

King's defense team in his tax case had challenged, without success, an all-white jury. Later, the exclusion of African Americans from juries was another of Fred Gray's accomplishments in destroying everything segregated he could find. In 1966, in Mitchell v. Johnson, Gray argued to an Alabama federal court that the process for selecting juries, in Macon County, Alabama, was rigged to exclude African Americans. A dramatically lower percentage of African Americans were called for jury services than their overall county population. The court ordered the county to take immediate corrective action.

With a career like Fred Gray's, the obvious question is whether one case stands out as most significant. Gray said yes. It is Gomillion v. Lightfoot, a case that laid the foundation for the concept of “one man, one vote.” In 1960, Gray convinced the Supreme Court that the city limits of Tuskegee had been gerrymandered for the purpose of excluding African Americans from voting in municipal elections.

Gray had been concerned about getting Justice Felix Frankfurter's vote. He shared with me that, during oral argument, Frankfurter was shocked to learn something about the new boundaries of Tuskegee that had been drawn. “You mean to tell me,” Frankfurter asked Gray, incredulously, “that Tuskegee Institute is outside the city limits of the City of Tuskegee?” Frankfurter authored the court's unanimous decision.

Gray told me that he believed what was done in Montgomery, and what other groups did, “all contributed to the election and re-election of President Obama.” And Gray is sure that Obama recognizes this. Leading the former president's 2009 inauguration parade was a replica of the bus on which Rosa Parks said no. Inscribed on the side: “It All Started on a Bus.”

For Fred Gray it has been a long ride. “A bus,” he said, “can take you from where you are, to where you want to go.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at Temple University Beasley School of Law.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

How I Made Partner: 'Be Open With Partners About Your Strengths,' Says Ha Jin Lee of Sullivan & Cromwell

How I Made Partner: 'Avoid Getting Stuck in a Moment,' Says Federico Cuadra Del Carmen of Baker McKenzie

How I Made Partner: 'Find Your Niche and Become the Go-To Person,' Says Shawn Hendricks of Stradley Ronon Stevens & Young

Trending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250