'I Just Made a Big Mistake.' Photograph Sparks Tense Exchange at Greg Craig Trial

A prosecutor mistakenly thought she had photographic evidence that appeared to catch a former Skadden partner in a lie.

August 27, 2019 at 09:57 PM

6 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

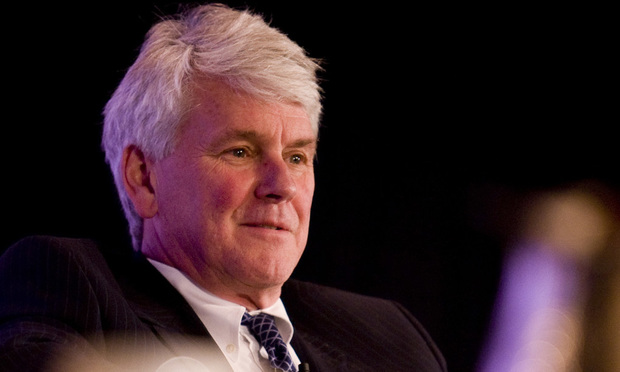

Gregory Craig. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ ALM)

Gregory Craig. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ ALM)

A federal prosecutor thought she might have caught Cliff Sloan in a lie Tuesday—and that she had the proof in hand.

U.S. District Judge Amy Berman Jackson of the District of Columbia had warned Greg Craig several days earlier to not interact with his former law firm colleagues as he stood trial in Washington federal court on charges that he misled the Justice Department about his work for Ukraine while he was a partner at Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. The judge's admonition underscored an awkward element of Craig's trial: His friends and former colleagues have been called to testify against him.

Among those friends and colleagues was Sloan, a former Skadden partner whom prosecutors originally summoned to the stand last week to testify about the Ukraine project now at the center of Craig's criminal trial. On Tuesday, Sloan returned to the stand as a defense witness, setting the stage for a tense cross-examination in which prosecutor Molly Gaston briefly appeared to question not only Sloan's truthfulness, but also whether Craig had defied Jackson's instruction to avoid interactions with his Skadden colleagues.

In his testimony Tuesday, Sloan described how Craig rebuffed efforts by the Ukrainian government to make changes to the report Skadden prepared in 2012 on the widely criticized prosecution of the country's former prime minister, Yulia Tymoshenko. Prosecutors have alleged that Craig, a former Obama White House counsel, misled the Justice Department about his role in the public release of the report to avoid registering as a foreign agent of Ukraine. Sloan's testimony appeared to bolster Craig's argument that the Tymoshenko report was independent and that he did not view himself as acting as a foreign agent of Ukraine.

Craig, who is expected to take the stand in his own defense Wednesday, has denied deceiving the Justice Department about his Ukraine work and argued he faced no obligation to report his activities under the Foreign Agents Registration Act, an 80-year-old law requiring the disclosure of foreign influence in the U.S.

At the end of her cross-examination Tuesday, Gaston made clear that Sloan was more than just a former colleague of Craig.

Cliff Sloan of Skadden (2009) Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM

Cliff Sloan of Skadden (2009) Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM"And finally, Mr. Sloan, you're friends with Mr. Craig, aren't you?" she asked.

"Yes," Sloan replied.

"You're close friends with Mr. Craig."

"Yes."

Gaston then asked whether Sloan had spoken with Craig after his testimony last week.

"With the defendant? No," Sloan answered.

"Did you leave the courthouse last week with Mr. Craig?" Gaston asked.

"No," Sloan said.

"You didn't?" Gaston asked.

"No," Sloan said.

Struck by the response, Gaston picked up a piece of paper and approached the bench, apparently believing she had photographic evidence of the longtime friends leaving court together Aug. 23. At the bench, a defense lawyer for Craig recognized the photograph from press coverage of the trial and said it had been taken a few years ago, when Craig and Sloan represented Gen. James "Hoss" Cartwright. The retired general pleaded guilty in 2016 to lying to the FBI in a leak investigation, and was later pardoned by President Barack Obama weeks before the retired general was to be sentenced.

"Then, I just made a big mistake," Gaston said, according to a transcript of the private discussion at the bench. Gaston then withdrew her question.

But Craig's defense team was not satisfied.

As jurors took their afternoon break, Craig's lead defense lawyer, Zuckerman Spaeder partner William Taylor, said some jurors might have caught a glimpse of the photograph. His concern gave rise to a debate over whether the paper in Gaston's hand was folded or rolled up—visible or not to the jurors.

"When she walked by the jury box," Taylor said, "the jury could see she had a photograph in her hand."

Prosecutor Fernando Campoamor-Sanchez said it was his "distinct recollection" that the paper in Gaston's hand was folded. "It was a photograph," he said, "but it was folded."

When the jurors returned to their seats, Jackson instructed them that there was "no evidence in the record" that Sloan spoke with Craig or exited the courthouse with him following his testimony Aug. 23.

"But there's also no suggestion or inference that you should draw that anyone did anything improper in asking to withdraw the question," the judge said. "The question was asked, it was answered 'no,' and that's what the evidence is."

Tuesday's tense courtroom exchange came against the backdrop of an admonition Jackson delivered two weeks earlier in the trial. On Aug. 16, Taylor disclosed to the judge that Craig had greeted Skadden partner Michael Loucks outside the courthouse the previous evening after his former colleague testified for prosecutors. Loucks, a former acting U.S. attorney in Massachusetts who worked on the Tymoshenko report, had yet to be cross-examined when Craig approached him outside the courthouse.

"Mr. Craig, this witness was in the middle of his testimony. He's still on the witness stand. He's not to be interacted with, nor are other witnesses in the case to be interacted with," Jackson said.

In addition to Loucks and Sloan, prosecutors called Craig's former secretary and Skadden's general counsel, Lawrence Spiegel, along with nearly a half dozen other witnesses with ties to the firm.

After Sloan's testimony Tuesday, Craig's defense team summoned four character witnesses, including Williams & Connolly partner Brendan Sullivan, a longtime leader of the firm. On the witness stand, Sullivan was asked whether he had an opinion about Craig's integrity.

"My opinion is that his integrity is beyond reproach," Sullivan replied.

In the cross-examination, Campoamor-Sanchez confirmed that Sullivan has not been attending the trial, in which prosecutors have presented evidence of Craig more closely involved in the public release of the Tymoshenko report than he led the Justice Department to believe.

Prosecutors have also highlighted the role Paul Manafort, the longtime political consultant, played in arranging for Skadden to take on the review of Tymoshenko's case in 2012, years before he became chairman of the Trump campaign.

Sullivan on Tuesday confirmed that he has not attended the trial or absorbed the prosecution's evidence.

"That is correct," Sullivan responded to the prosecutor. "'I'm a character witness."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

In-House Moves of the Month: Boeing Loses Another Lawyer, HubSpot Legal Chief Out After 2 Years

5 minute read

After Regime Change, Syria Remains Liable in US Federal Courts for Alleged Assad-Era Terrorism Support

3 minute read

Carrier Legal Chief Departs for GC Post at Defense Giant Lockheed Martin

Trending Stories

- 1New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 2No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 3Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 4Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 5Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250