Pharmacies in Opioid Case Want Judge to Ban Ex Parte Communications

U.S. District Judge Dan Polster of the Northern District of Ohio issued an order Thursday stating that the court was "mindful of its ethical obligations" after a group of pharmacy defendants insisted on banning ex parte communications they believe are happening in the opioid litigation.

December 06, 2019 at 06:45 PM

9 minute read

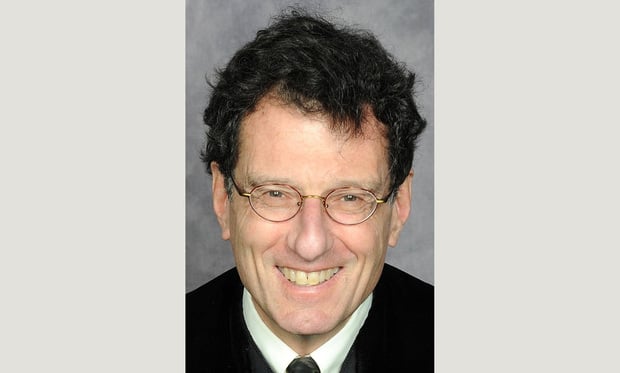

Judge Dan Polster, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio. (Courtesy photo)

Judge Dan Polster, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio. (Courtesy photo)

After reaching a multimillion-dollar settlement with drug companies in October that averted the first trial over the opioid crisis, lead plaintiffs lawyers are gearing up for the next trial: this time, against six pharmacies including Walgreens and CVS.

Ahead of that trial, the pharmacies, however, have revived concerns about judicial conduct in the opioid litigation.

The day before a Dec. 4 hearing about the trial, they asked U.S. District Judge Dan Polster of the Northern District of Ohio to issue an unusual order barring ex parte communications with himself or any of the three special masters as to "substantive matters," such as discovery deadlines and trial dates, as well as settlement discussions. They cited a canon of the Code of Conduct for United States Judges governing ex parte communications, which are discussions a judge has with the parties or their lawyers outside the presence of the opposing parties.

Polster, in a Dec. 5 minute order, declared the motion moot.

"The court has always been and will continue to be mindful of its ethical obligations as set forth in the Code of Conduct for United States Judges," he wrote. "Per the Canon, neither the court, nor its Special Masters, will engage in any settlement discussions with the CT1B parties regarding CT1B unless and until all parties agree and ask the Court to do so," referring to the parties in the case against the pharmacies.

The move, however, comes a month after the pharmacies raised similar concerns about decisions Polster purportedly made outside of the courtroom and without them being present. It also comes after the pharmacies and another group of defendants, the drug companies that distribute opiate pharmaceuticals, unsuccessfully sought Polster's recusal earlier this year, citing an appearance of impartiality based on statements he made about the litigation to the media.

Improper ex parte communications also can result in disqualification, as well as potential disciplinary action or reversal on appeal, said Charles Geyh, a professor at Indiana University, Bloomington, Maurer School of Law, who co-wrote "Judicial Conduct and Ethics." As a result, most judges try to avoid ex parte communications, or limit them to administrative or scheduling matters.

"It is a serious business, and I don't mean to imply these serious problems occurred in this case at all," he said. "We don't know. But I do mean to say that most judges understand the problems and avoid them. They don't engage in ex parte communications. It is the exception, a judge who does."

Lawyers for each of the pharmacy defendants either declined to comment or did not respond to requests for comment. Polster also did not respond to a request for comment.

Lead plaintiffs attorneys—Paul Hanly, of Simmons Hanly Conroy; Paul Farrell of Greene, Ketchum, Farrell, Bailey & Tweel; and Joe Rice of Motley Rice—said in an emailed statement: "These complaints from the pharmacies were addressed by the court and are without merit. This is another use of the same tactics we have seen time and time again from defendants to delay justice for Ohio communities."

In court papers, the pharmacies cited Canon 3(A)(4), which states that ex parte communications are allowed only if they do not address "substantive matters," and if the judge "reasonably believes that no party will gain a procedural, substantive, or tactical advantage as a result of the ex parte communication."

The rule also permits ex parte communications for settlement discussions but "with the consent of the parties."

"That's OK if everybody is agreeable," Geyh said. However, he said that does not sound like the case here.

It's not the first time Polster has come under fire from the defendants. In both the ex parte communications filing, and the prior recusal attempt, the defendants appear to indicate a belief that the judge was "overly invested" in solving the opioid crisis at the expense of their receiving fair treatment, Geyh said.

"That's one of the telltale signs of overreaching: the possibility the masters or judge are engaging in ex parte communications," he said. "You have these suspicions you can't confirm but seem to be in some ways legitimized by the masters and judge being in possession of information that they couldn't seem to have acquired except by someone under circumstances that didn't occur in open court."

In his Sept. 26 order refusing to recuse himself, Polster stated, "I freely admit I have been very active from the outset of this MDL in encouraging all sides to consider settlement." Doing so, he wrote, has not compromised his ability to be fair and impartial, and actually helped reach some settlements so far in the opioid litigation.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit affirmed his decision Oct. 10.

The Sixth Circuit, however, reversed Polster on another issue: public disclosure of a drug database at the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration that provided the total number of opioid pills tied to each of the drug companies. On June 20, the Sixth Circuit found Polster had no reason to keep most of the database confidential, which the defendants had requested.

Polster also has kept most court hearings closed to the media and public, prompting some of the defendants to request that a court reporter be available.

Ex Parte Communications

The latest dispute began soon after reaching the $260 million settlement just hours before an Oct. 21 trial was set to begin in Polster's courtroom in Cleveland. The settlement resolved claims by two Ohio counties against four of the five companies scheduled for trial: McKesson Corp., Cardinal Health Inc. and AmerisourceBergen Corp., as well as Teva Pharmaceuticals, a pharmaceutical manufacturer.

In court filings days later, plaintiffs lawyers said the remaining defendant, Walgreens, and five other pharmacies, could face trial as soon as early 2020.

That was news to the pharmacies.

In their own court documents, filed ahead of a hearing to discuss the "next steps" in the opioid litigation, they wrote that "third parties have told the pharmacy defendants that the court has already decided important agenda items for the November 6 status conference without giving the pharmacy defendants an opportunity to be heard."

"Any such pre-decision of disputed issues would be improper," they wrote. "This court, like every other, should withhold judgment on substantive issues until all parties have been heard on the record and should not render decisions based on incomplete information and argument communicated ex parte."

Specifically, they wrote, a journalist informed them that the Ohio trial could occur in the spring.

"If true," they wrote, "such determination was made without consulting the pharmacy defendants on counsel's availability, the needs of the case, or the wisdom of a spring trial date."

They also heard from one of the special masters that Polster had already granted a motion by plaintiffs lawyers to amend the complaint, brought by the same two Ohio counties, to add claims against the pharmacies. That was before the pharmacies, which later opposed such an amendment, had "any opportunity to present their position, and before the subject ever was discussed in open court," they wrote.

"To the extent the court decided to allow amendment before the filing of any motion for leave to amend—much less a response—its decision was clearly improper," they wrote. "Such a decision could have been based only on either an ex parte request by plaintiffs or the court's own views about which unasserted claims plaintiffs should have pursued and prepared for trial. Neither of these would be a permissible ground for the court's decision."

Their filing, called a position paper, asked Polster to issue an order prohibiting "further ex parte communications with the court or any of the special masters" regarding the motion to amend the complaint.

"The pharmacy defendants are entitled to a fair hearing on the issue, on the record and before a judge committed to hearing from all parties before making a decision," they wrote.

In other court filings, the pharmacies opposed the Ohio trial, insisting it would be "monumentally unfair" and suggested that governments in other jurisdictions go forward with planned trials next year.

On Nov. 19, Polster granted the plaintiffs' motion to amend the Ohio complaint and scheduled the trial for October 2020. The pharmacies, in a response, noted that Polster had not given them a chance to discuss particulars of such a trial, such as the amount of discovery or the number of depositions, and asked for a hearing.

That hearing was Dec. 4. One day earlier, the pharmacies sought their ban on ex parte communications.

"The order must bar, without limitation, ex parte communications on any disputed or potentially disputed issue, ex parte communications on any legal, factual, or discovery issue, and ex parte communications on all case management subjects such as case management orders, discovery deadlines, trial dates, case tracks, remands, and amendments," as well as settlement discussions, they wrote.

The pharmacies cited no proof of specific ex parte communications the judge had with other parties. But that might not matter, Geyh said.

"My sense of it is this was a strategic move from the get-go from the defendants," he said. "It really didn't matter to them whether the judge granted the order or denied the order. What mattered is this was an opportunity for them to flag the issue and make it known that they were concerned this was going on and make the judge say something about it, which the judge did."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trump Administration Faces Legal Challenge Over EO Impacting Federal Workers

3 minute read

US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

3 minute read

The Right Amount?: Federal Judge Weighs $1.8M Attorney Fee Request with Strip Club's $15K Award

Skadden and Steptoe, Defending Amex GBT, Blasts Biden DOJ's Antitrust Lawsuit Over Merger Proposal

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Pogo Stick Maker Wants Financing Company to Pay $20M After Bailing Out Client

- 2Goldman Sachs Secures Dismissal of Celebrity Manager's Lawsuit Over Failed Deal

- 3Trump Moves to Withdraw Applications to Halt Now-Completed Sentencing

- 4Trump's RTO Mandate May Have Some Gov't Lawyers Polishing Their Resumes

- 5A Judge Is Raising Questions About Docket Rotation

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250