Conversation With Samantha Power: New Memoir on Her Path From War Zone to Classroom

In her recently published book, the Harvard Law School professor recounts her career as a journalist, presidential adviser and diplomat.

January 06, 2020 at 02:16 PM

8 minute read

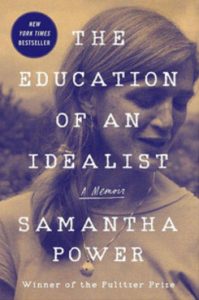

Samantha Power. Photo: Shutterstock

Samantha Power. Photo: Shutterstock

As a student at Yale University, Samantha Power was sports-obsessed and studying for a career in sports journalism.

But something happened to set her on a different course. While witnessing the 1989 protests against the Chinese government in Tiananmen Square, where many students were killed in the cause of democratic reforms, Power wondered if she "should be doing something more useful than thinking about sports all the time." The next semester she became a history major.

In her recently published memoir, "The Education of an Idealist" (Dey St.), the former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations recounts her career as a journalist, presidential adviser and diplomat—all set in motion by the indelible image she saw of a lone Chinese protester standing in the way of a tank.

These days, Power is a professor at Harvard Law School, her alma mater, where she likes to help students with their own career choices. "My students are looking for pathways," Power tells me by phone. She encourages public service, but adds "I'm not judgmental at all about different pathways people can take. Although I do try to show the good you can do."

These days, Power is a professor at Harvard Law School, her alma mater, where she likes to help students with their own career choices. "My students are looking for pathways," Power tells me by phone. She encourages public service, but adds "I'm not judgmental at all about different pathways people can take. Although I do try to show the good you can do."

While driving from her home in Concord, Massachusetts, to Harvard's Kennedy School of Government in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she is also a professor, Power shared with me her own pathway. Nothing about it was typical. Her road to becoming a law student started in a war zone. Her time in law school was accompanied by a separate course of study in human rights. And her legal education was put to use on foreign policy stages.

Even now, Power remains different. One of her courses at the law school is co-taught with her husband, well-known professor Cass Sunstein.

Power had an unlikely start for a U.S. ambassador to the U.N. She was born in London to Irish parents and raised in Dublin. In her autobiography, she tells the story of a challenging upbringing on account of her father's struggle with alcohol. In 1979, at age 9, she moved to Pittsburgh with her mother, a physician. She says she threw herself into American life, learned how to play basketball and had a poster of Pirates left fielder Mike Easler on her bedroom wall.

While Tiananmen Square sparked Power's interest in current affairs, other significant events were happening at about the same time. She points to the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the beginning of the end of apartheid in South Africa. Power describes these events as the "end of a horrific division that had paralyzed international affairs and bloodied it for so many decades." It was a time of "hope," she said, and international affairs was "a very attractive field to get into."

Power did. After Yale, she took an internship at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a policy institute in Washington. Her work focused on the war in Bosnia that followed the collapse of Yugoslavia. Power made the decision to travel to the Balkans and work as a freelance correspondent, covering the brutality and ethnic cleansing by Serbian militants.

Knowing she needed a press pass, Power forged a letter from the editor of the Carnegie Endowment's journal to the United Nation's press office. It seems an odd introduction to the U.N. for the future U.S. ambassador, I point out.

"I certainly don't feel good about that," Power tells me. She says she was mixed about whether to include this confession in her memoir. But it "showed that each of us is imperfect in our own way." She adds, "Obviously I was very driven, and it shows that as well." But she also is quick to note: "I'm not recommending this for others."

Press pass in hand, Power spent two years risking her life in the war zone, producing pieces for numerous national media.

After Bosnia, Power headed back to school. Given her interest in foreign affairs, the obvious place to go, she told me, was graduate school.

"But there was something about the law that seemed more practical," Power explains. And "it wasn't just the illusion of practicality," she adds. "It actually seemed like there was something I could do on the very issues I cared about if I went and got a law degree." She also had good timing. "The field of international criminal law was really taking off." Power considered studying to become a war crimes prosecutor.

Power's arrival at Harvard Law School was met with "buyer's remorse." The war in Bosnia was coming to an end, she tells me. "My first days on campus I felt like, 'what the heck am I doing here?,' I should be reporting on this history that's being made."

She also faced an initial lack of enthusiasm for the material. Writing in her memoir, she says: "While I admired the poise of my classmates who threw themselves into Socratic debates with their peers and professors, I just couldn't make myself care about the topics we were studying."

But things changed. "I started to feel myself getting better and sharper and suspending, for the sake of argument, what side of an issue I was on," Power explains. "I was getting better at teasing out how to be an effective prosecutor of my objective."

Returning to the interests she developed in Bosnia, Power began to study the American response to genocide, taking classes at both the law school and Harvard College. At this point, she explains, "I was taking from law school what I felt law school could give me, rather than that 1L experience where you are put into a mold, that felt very deliberate, that was not of your choosing." The work she started in this area while at Harvard led to her winning the Pulitzer Prize in 2003 for "A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide."

Following graduation, Power went to work as the founding executive director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at the Kennedy School, which describes itself as using various approaches to address human rights challenges of the new century, including genocide, mass atrocity, state failure and the ethics and politics of military intervention.

Then Washington called and Power began a long relationship with Barack Obama, first in his U.S. Senate office, then on his 2008 presidential campaign and, finally, during his two presidential tours of duty. From 2009 to 2013, Power served on the National Security Council. This was followed by over three years in Obama's cabinet as ambassador to the U.N.

"When I was at the U.N. [my law degree] was indispensable," Power tells me. Because of it, she says that there was "no mystification around government lawyers or lawyers representing other countries." Power had high praise for her lawyers. But she tells me that she "had no problem going toe-to-toe with" them.

"I saw other policymakers where the lawyer would speak and that would end the conversation." But on account of her training, Power was less inclined to remain silent. "For me, 'Are there any counter-arguments?' At least ask the lawyers 'are there contrary legal opinions?' And then you immediately hear 'yes there are.'"

This semester Power will be teaching two courses at HLS. The offering with Sunstein is called Making Change When Change is Hard: The Law, Politics, and Policy of Social Change. "We look at the question of how change happens," Power explains. "Is it through the courts? Is it through social movement? Is it through domestic politics? We look at a bunch of different lenses."

Is there any spousal banter during class?, I wonder. "We both worked for the Obama administration, but we have pretty different takes on things." But "it's not Justice Scalia and Justice Stevens duking it out."

"He thinks he's funnier than I am. But I'm not sure about that."

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at Temple University Beasley School of Law.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Fired by Trump, EEOC's First Blind GC Lands at Nonprofit Targeting Abuses of Power

3 minute read

'Erroneous Rulings'?: Wilmer Asks 4th Circuit to Overturn Mosby's Criminal Convictions

3 minute read

LSU General Counsel Quits Amid Fracas Over First Amendment Rights of Law Professor

7 minute read

Zoom Faces Intellectual Property Suit Over AI-Based Augmented Video Conferencing

3 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Big Law Firms Sheppard Mullin, Morgan Lewis and Baker Botts Add Partners in Houston

- 2Lack of Jurisdiction Dooms Child Sex Abuse Claim Against Archdiocese of Philadelphia, says NJ Supreme Court

- 3DC Lawsuits Seek to Prevent Mass Firings and Public Naming of FBI Agents

- 4Growth of California Firms Exceeded Expectations, Survey of Managing Partners Says

- 5Blank Rome Adds Life Sciences Trio From Reed Smith

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250