Justice Thomas, in Lone Dissent, Thrashes 'Chevron' and His Own 'Brand X' Decision

Thomas regularly writes solo dissents, urging his colleagues to revisit, or even strike down, earlier rulings. But it's rare for any justice to cast doubt on a prior ruling the justice had earlier written.

February 24, 2020 at 03:18 PM

6 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

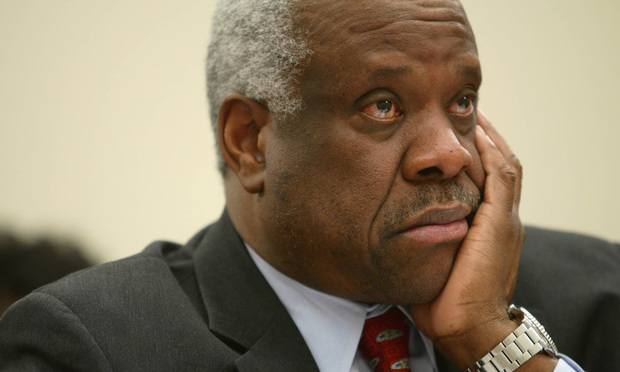

Justice Clarence Thomas (2013). Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

Justice Clarence Thomas (2013). Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

Justice Clarence Thomas on Monday sharply criticized his own majority opinion in a 15-year-old telecommunications case and an underlying decision that says courts must give deference to agencies interpreting their own regulations, urging his colleagues to reconsider both rulings.

Thomas wrote alone in an 11-page dissent that said the Supreme Court should have agreed to review the tax case Baldwin v. United States. The Baldwin petition, arriving from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, had asked the justices outright to overrule Thomas's 2005 decision in National Cable & Telecommunications Assn. v. Brand X Internet Services, a regulatory case that said a federal agency had correctly interpreted the Communications Act of 1934.

Thomas used the Baldwin case to raise and advance his concerns about his prior Brand X decision, and the underlying doctrine called "Chevron deference," a bedrock part of administrative law that says courts generally adopt agencies's views, if reasonable, of their rules. That deference has drawn criticism from conservatives members of the court, but no justice has moved to overturn the 1984 ruling.

"Even if the court is not willing to question Chevron itself, at the very least, we should consider taking a step away from the abyss by revisiting Brand X," Thomas wrote in Monday's dissent. Quoting a statement from the late Justice Robert Jackson in a 1950 ruling, Thomas said: "It is never too late to 'surrende[r] former views to a better considered position.'"

Thomas regularly writes solo dissents, urging his colleagues to revisit, or even strike down, earlier rulings. But it's rare for any justice to cast doubt on a prior ruling the justice had earlier written.

Critical to the Brand X decision was the majority's view, led by Thomas, that it "follows from Chevron" that a court must abandon its previous interpretation of a statute in favor of the agency's interpretation unless the prior court decision found the statute was unambiguous.

"Regrettably, Brand X has taken this court to the precipice of administrative absolutism," Thomas said Monday. "Brand X may well follow from Chevron, but in so doing, it poignantly lays bare the flaws of our entire executive-deference jurisprudence."

Expressing what he called "skepticism" of the Brand X ruling, Thomas said his decision now "appears to be inconsistent with the Constitution, the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), and traditional tools of statutory interpretation."

The Supreme Court's 1984 decision Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council held that courts generally must accept an agency's interpretation of an ambiguous statute if the interpretation is reasonable. That decision is in "serious tension" with the Constitution, the Administrative Procedure Act and "over 100 years of judicial decisions," Thomas wrote Monday.

Thomas has criticized the Chevron doctrine in prior opinions, as have other justices, including Justice Neil Gorsuch. He repeated many of those criticisms in Monday's dissent. Thomas argued that the Chevron decision gives federal agencies unconstitutional power and undermines the ability of the judiciary to perform its checking function on the other branches.

Appellate veteran Elbert Lin of Hunton Andrews Kurth noted that Thomas' criticism of Chevron on Monday went further than it had before. Thomas had said in the past that there could be "some unique historical justification for deferring to federal agencies." In Monday's statement, Thomas said, "it now appears to me that there is no such special justification."

Thomas' combination of his criticism of Chevron with his disavowal of his Brand X opinion was striking.

"Chevron requires judges to surrender their independent judgment to the will of the executive; Brand X forces them to do so despite a controlling precedent," Thomas wrote. He continued: "Chevron transfers power to agencies; Brand X gives agencies the power to effectively overrule judicial precedents. Chevron withdraws a crucial check on the executive from the separation of powers; Brand X gives the Executive the ability to neutralize a previously exercised check by the judiciary."

The Baldwin petition was a challenge to a ruling by U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The appellate court gave deference to a new interpretation by the Internal Revenue Service of the deadline for requesting tax refunds. Aditya Dynar of the New Civil Liberties Alliance was counsel to Howard and Karen Baldwin.

"Their decision to not take the Baldwins' case is going to negatively affect judicial independence for years to come," Dynar said in a statement. "And it is going to dilute the continued legitimacy and finality of court decisions. We are currently reviewing next steps in terms of bringing this issue back up in a different case."

U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi / NLJ

U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi / NLJThe Justice Department had urged the Supreme Court to turn down the petition. "As long as Chevron remains the law, there is no sound reason to reconsider Brand X, and petitioners do not ask the court to revisit Chevron," U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco told the justices.

"As this court recognized in Brand X itself, the rule the court adopted there 'follows from Chevron,'" Francisco wrote. "Petitioners have not asked this court to overrule Chevron, and this case is not a suitable vehicle for considering that step."

Francisco also told the court: "It would make little sense for a court of appeals to decline to give effect to an agency regulation that is otherwise entitled to deference, simply because a prior panel of the same court had interpreted an ambiguous statute differently before the regulation was promulgated."

Read more:

Gorsuch and Thomas Decry 'Chaos' of National Injunctions, as Judges Check Trump

How Clarence Thomas Starred in Fifth Circuit's Ruling Against Obamacare

Justice Clarence Thomas Stirs Up a First Amendment Squabble Over Libel Law

Clarence Thomas Asserts National Injunctions Are 'Historically Dubious'

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute read

Attorney Sanctioned $9K for Revealing Nude Photos, Other Info in Court Filing

4 minute read

Chicago Cubs' IP Claim to Continue Against Wrigley View Rooftop, Judge Rules

2 minute read

After Solving Problems for Presidents, Ron Klain Now Applying Legal Prowess to Helping Airbnb Overturn NYC Ban

7 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250