Linking Partner Pay to Strategic Firm Objectives

Pay for performance is not a new concept in this country. The ideas and concepts underlying a graduated pay scale based on contribution and merit are deeply ingrained in our society. However, in general law firms have been slower to adopt pay for performance systems. What law firms need now, and this article describes, is an approach to partner compensation that closely links a partners pay to their ability to contribute to the achievement of the firm's strategic objectives.

February 25, 2020 at 10:14 AM

12 minute read

This article appeared in Accounting and Financial Planning for Law Firms, an ALM/Law Journal Newsletters publication covering all financial aspects of managing law firms, including: building a law firm budget; rates and rate arrangements with clients; coordinating benefits for law firm partners; and the newest strategies to grow your firm and your career.

Pay for performance is not a new concept in this country. The ideas and concepts underlying a graduated pay scale based on contribution and merit are deeply ingrained in our society and date back at least to Adam Smith and the Scottish Renaissance. And despite some recent, spectacular aberrations at the top of some of America's largest corporations pay for performance in the corporate setting has served this country well.

However, in general law firms have been slower to adopt pay for performance systems. There were many reasons for this. First and foremost, the law was thought of as "A Profession" not a job and partner compensation reflected not only the work that one did but a return on invested capital and the number of years an individual had been at the firm. It was not unusual for old law firm lock step pay systems to increase compensation as a partner aged (and presumably had additional financial responsibilities brought on by a family) peak in the mid-fifties and then decline (as the financial obligations of colleges and marriages decreased) through the partners later years.

Those lock step systems gradually gave way to the "Scorecard" pay systems that predominate in law firms to this day. In these systems, objectives were set for each partner in a number of quantifiable areas such as originations, recorded billable hours and billed fees. These systems, which may have served law firms in the past, do not provide a law firm's management with the proper tools to incent partner behavior into those activities that will help a firm achieve its strategic objectives. Indeed, some of these systems are so heavily weighted to the wrong compensable factors that they actually hinder a firm's ability to succeed.

What law firms need now, and this article describes, is an approach to partner compensation that closely links a partners pay to their ability to contribute to the achievement of the firm's strategic objectives and provides firm management with the tools it needs to not only achieve current strategic objectives but to build those skills and attributes within the firm that will enable the firm to meet future objectives and challenges.

There are four key requirements to implementing a performance linked partner pay system. They include:

- Clearly defined and broadly supported firm vision and a strategy for achieving that vision.

- Differentiated contribution roles for partners within the partnership with explicit expectations and a clear definition of success in each role.

- Structured goal-setting and evaluation processes that provides partners with actionable feedback.

- Availability of substantive data that will allow partners to personally validate compensation decisions using available guidelines and criteria.

Within each of these requirements there are a number of tasks and activities that must be undertaken to ensure their successful completion. They are:

Vision and Strategy

Vision and strategy are the logical starting points for a law firm's partner compensation program. After all, if a firm does not know where it is going, how can it direct and reward those actions that will get it there. Although strategy development can be (and has been) a long and arduous process it need not be. A law firm can develop strategy by answering a series of questions, including the following.

- In what practices does the firm enjoy competitive advantages?

- How much capital (human and monetary) can the firm invest in building those competitive advantages?

- Where does the firm wish to invest its capital?

- What is the firm's culture?

- What aspects of that culture is the firm unwilling to change?

- Are there some aspects of its culture that the firm wants to change?

- What types of partner behavior does the firm want or need to change?

- Who "owns" the firm's clients?

- What behavior does the firm need or want to reward?

This list is by no means exhaustive, but it demonstrates the breadth of issues that a strategy and its supporting compensation system must address. A firm's responses to these questions will also help to define partner contribution roles — that is to say, how each individual partner will make his or her maximum contribution to the achievement of the firm's strategic objectives utilizing their individual strengths. In turn, these roles provide a framework within which expectations can be set and performance evaluated. The importance of a firm's strategic vision cannot be overemphasized. The recent failure of several firms around the country can, I believe, be traced in part to their lack of a clear strategic vision and a mechanism to direct partner efforts toward the achievement of that vision.

Contribution Roles

No one expects every member of an athletic team to perform the same tasks. There are positions in each sport and each position contributes to the success of the team in a different way. If we expect different contributions to winning from a quarterback and a linebacker why then do, we expect every partner in a law firm to contribute in the same way and at the same level to a law firm's success.

Contribution roles recognize these differences, identify those key performance measures within each role that success can be measured by and provides a logical progression from role to role.

Typically, there are four to five different contribution roles within a law firm. These roles might be identified by different titles such as: Individual Contributor, Subject Matter Contributor, Responsible Contributor, Client Contributor and Administrative Contributor.

Expectations and performance metrics are defined by a firm for each role and while (at a high level) they are broadly similar they are specific to each firm that defines them.

As an example, a firm might define the Responsible Contributor role as partners who are charged with managing individual matters within their field of expertise. The partners would be responsible for selecting and managing the other partners and associates who perform the work, identifying the issues involved in the matter, co-coordinating the development and execution of the approach to resolving the client's matter and day to day client communication. In short, the Responsible Contributor would be responsible for the overall successful completion of individual client matters.

Metrics to measure a Responsible Contributor might include; fee realization percent on matters, net fees per hour on all matters managed, imputed interest on accounts receivable, etc.

In addition to specific quantitative metrics for each contribution role other qualitative metrics would also be applied. These might include quality of work performed, degree of associate mentoring, public service, firm committee work and support of firm administrative policies.

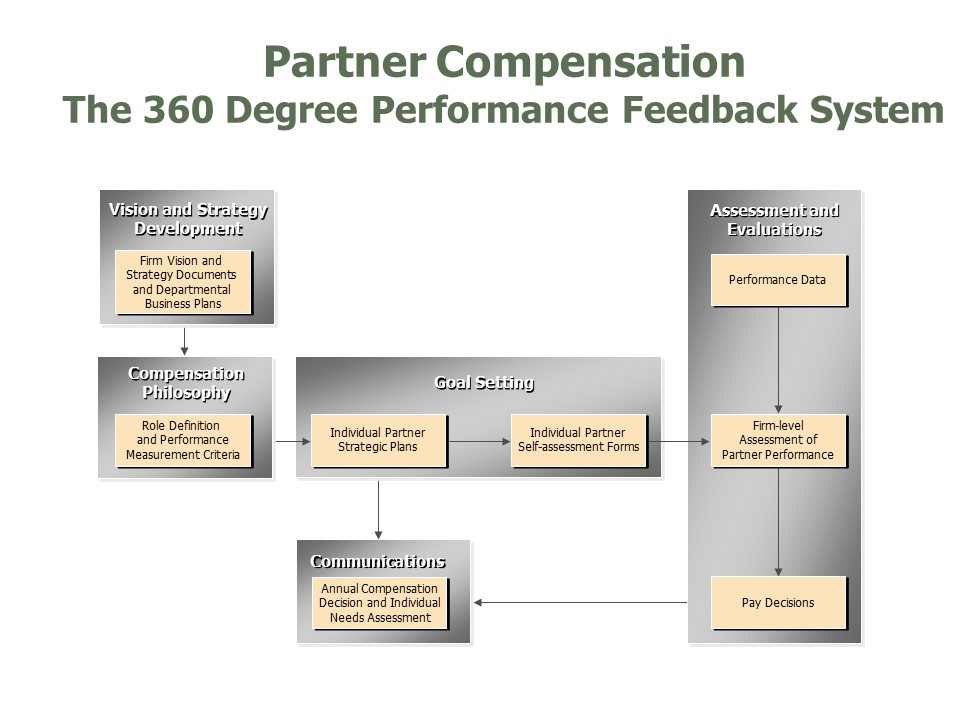

The graphic below illustrates the 360 degree compensation system.

Individual Partner Goal Setting

This phase has two distinct steps. First, each partner develops an individual "contract" outlining how he or she will contribute to the firm's overall success. These contracts are developed late in the year) or early in the New Year) in connection with the firm's business planning cycle. The contracts are based on the previously developed contribution roles noted above. For example, partners Smith and Jones are in the same law school class. Partner Jones is a truly great litigator who attracts, and usually wins, significant cases. On the other hand, partner Smith is a brilliant technician with ability to manage and remember hundreds of individual facts and circumstances in complex business negotiations. The best use of these individuals is quite different. Partner Jones's role in the firm would be that of an Individual Contributor while partner Smith might be called upon to be a Responsible Contributor. Each partner's plan would recognize their areas of expertise and, in light of their different roles, establish different objectives and evaluative criteria. Partner Jones, as an Individual Contributor, might be evaluated on the quality of his work, the complexity of the litigation he handles, and his responsiveness to clients. As a Responsible Contributor, partner Smith is evaluated on the selection and management of the attorneys performing the assignment, identification of additional services the firm might provide to the client, and (of course) the quality of the work performed.

The second step of this phase occurs late in the firm's business year and requires each partner to submit a written self-assessment of their performance against the contract they developed at the beginning of the year to the firm's management. This assessment compares the year's goals contained in the contract with the partner's actual achievements. The assessment also enables the partner to notify management of other noteworthy accomplishments for the year that were not in the original contract.

Assessment and Evaluation

Near the end of the year, the assessment process begins. Individual partners meet with their evaluator — department head, office manager, compensation committee member, or Managing Partner — to review their prior year's achievements. This conversation is based on the individual partner's contract and the year's actual results. Individual partner performance data – "the numbers" — are still a major topic of discussion, but performance in more subjective areas, such as attorney development, practice enhancement, and firm management are also included.

When the individual meetings conclude, the evaluators get together and, based upon the firm's overall strategy and needs, evaluate the partners relative to each other. This process groups partners into various hierarchical levels and allows for a firm wide "equity" evaluation.

It is important that individual partners be able to independently confirm their performance evaluation on a periodic basis and, at the end of the year, validate the firm's pay decisions. Therefore, whatever criteria a firm uses to evaluate its partners — client development, management, billing, collections — the firm's management information system must provide a ready means for individual partners to assess his or her performance. If partners are measured on something, appropriate information should be available so they can "keep score."

Communicating Pay Decisions

The final phase of any compensation program — and the one most frequently overlooked — is communicating final results to the individual partners. Firms that downplay the importance of effective communication squander one of their best opportunities to direct partner behavior and improve firm performance.

An appropriate member of the firm — Department Head, Office Manager, Compensation Committee member or Executive Committee Member — and the individual partner should discuss the individual's pay and bonus decisions. These discussions should clearly and directly link the pay and bonus decisions to the partner's actual performance, compared with the goals set in their individual contracts and previously defined role within the firm. This is an opportunity to explain, "why you got what you got," and to discuss how individual partner's strengths can be leveraged and what weaknesses need to be addressed. It may also be an appropriate time to discuss partner's long-term career goals and opportunities at the firm and that individual's role in the firm.

The Partnership Compensation System

This annual review process is also the starting point for the upcoming year's compensation cycle when partners begin to prepare their new individual contracts for the New Year based on these discussions.

Closing the Loop

By closing the compensation "loop," the compensation system becomes an effective mechanism for directing partner behavior and achieving the firm's strategy. As firms recognize, and adapt to succeed in, their changing environment, the compensation system can help individual partners appreciate the integral part they play in their firm's long-term success. As in all change, the most difficult step is the first. Before embarking on a major overhaul of its compensation system, a firm needs the following components:

- A clear, broadly share, articulated vision of where the firm is going.

- A management group that is committed to undertake the substantial and on-going work required to achieve the firm's vision.

- A Managing Partner with both the patience and the drive to take day-to-day responsibility for implementing and managing the necessary changes.

- A partnership that understands and supports the firm's vision and strategy, as well as the behavioral changes required to achieve the firm's goals.

Revising a compensation system in a partnership is a long and arduous process. It strikes at the foundations of the firm and any revision has as much potential for ill as good effects on a firm. Change should be undertaken neither lightly nor with the expectation that any fix to the compensation system is permanent. Compensation systems need annual reviews and periodic adjustments to ensure that they correctly reflect the firm's current thinking about its strategy and how best to achieve success.

*****

Mark Santiago is a member of the Board of Editors of Accounting and Financial Planning for Law Firms and a certified management consultant. He is the managing partner of SB2 Consultants, headquartered in New York City. Santiago has consulted to the legal profession for more than 25 years in the areas of financial performance improvement, compensation systems, merger/acquisition due diligence and integration, and administrative support outsourcing. A frequent speaker and author, he was one of the three originators of LegalTech in 1981 and is a member of its Advisory Board.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'If the Job Is Better, You Get Better': Chief District Judge Discusses Overcoming Negative Perceptions During Q&A

Scammers Target Lawyers Across Country With Fake Court Notices

Unlocking Your Lawyers' Rainmaking Potential: A Coaching Guide

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250