A Rare 'Damn' Reverberates Among US Supreme Court Advocates

Shocking? Hardly. But still striking. The word "damn" has rarely been uttered in the modern history of the U.S. Supreme Court.

February 26, 2020 at 02:50 PM

5 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

White & Case partner Christopher Curran on Tuesday argued for Sudan at the U.S. Supreme Court.

White & Case partner Christopher Curran on Tuesday argued for Sudan at the U.S. Supreme Court.

The word "damn" easily slips off the lips of many people, as it is so much a part of today's lexicon. But in the formal environment of the U.S. Supreme Court, an advocate's use of the word during arguments Monday resounded with some lawyers present.

The utterance came in the case Opati v. Republic of Sudan in an exchange between Sudan's lawyer, Christopher Curran of White & Case, and Justice Stephen Breyer. Curran argued a Supreme Court precedent had held that retroactive imposition of punitive damages was a "draconian step" and against the basic principles of fairness.

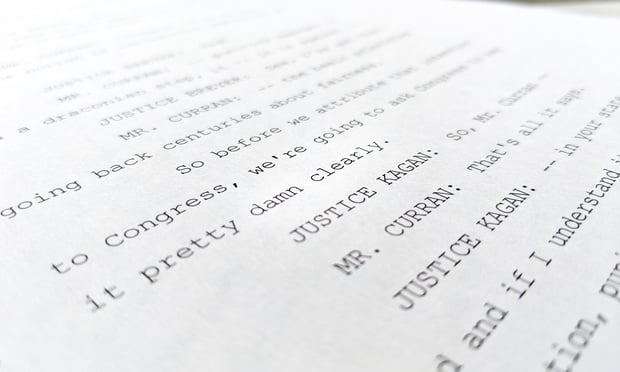

"So before we attribute that intention to Congress, we're going to ask Congress to say it pretty damn clearly," said Curran, paraphrasing the 1994 decision in the case Landgraf v. USI Film Products.

Shocking? Hardly. But definitely striking. Advocates at the Supreme Court tend to go to great lengths to avoid saying expletives or profanity, even in those instances where a particular word or words are central to the case. In last term's challenge to the federal bar on registration of scandalous and immoral trademarks, one of the lawyers in the case made it clear in a footnote in his brief that there would be no mention of the mark at issue: "FUCT."

"It is not expected that it will be necessary to refer to vulgar terms during argument," John Sommer of Irvine, California, wrote. "If it should be necessary, the discussion will be purely clinical, analogous to when medical terms are discussed."

During arguments in the case, Iancu v. Brunetti, Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart referred to "FUCT" only as the "past participle form of a well-known word of profanity." Going back much farther in time, none of George Carlin's "seven dirty words" made it into the arguments in Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica in 1978.

Curran's use of "damn" was striking because the word "damn" has rarely been uttered in the modern history of the Supreme Court. A search of oral argument transcripts from 1950 to 2015 found the word used only a handful of times, including at least once from an advocate and other mentions from the justices themselves. In other instances, advocates were quoting from the record of the case.

The one usage was by the late Tim Weaver, counsel to the Confederate Yakima Nation in the 1989 zoning case Brendale v. Confederate Yakima Nation. Weaver told the justices: "What happens on this piece of property directly affects what happens on the next piece of property. If someone wants to build a garbage dump next to your house, it's pretty damn difficult for you to say to the zoning authority: 'Gee, you ought to just stick on that piece of property and not let that use override onto my property.'"

Breyer used "damn" during 1997 arguments in Richardson v. McKnight. And Chief Justice William Rehnquist said the word during 1974 arguments in Donnolley v. Dechristoforo.

Some advocates, reached by The National Law Journal, were reluctant to speak to Curran's use of the word. "I would not want to comment on another advocate," one Supreme Court lawyer said. But other veterans spoke more generally to its use during arguments.

"My personal opinion is that things like that, unless carefully considered, can distract from the substance of the message being conveyed," said Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher partner and former U.S. Solicitor General Theodore Olson. "I try to avoid any slang, vernacular, argot, colloquialisms, street language, triteness or hyperbole. There may be times when something like that works, but very rarely, it seems to me."

Former Jenner & Block partner Paul Smith, now vice president of litigation strategy at the Campaign Legal Center, said "damn" should be avoided in high court arguments. "Supreme Court arguments can be done well in a conversational style, but this just seems a little jarring to me," Smith said.

David Frederick, a partner at Kellogg, Hansen, Todd, Figel & Frederick and author of "Supreme Court and Appellate Advocacy," said, "I'm not a fan of using swear words in any court, much less the Supreme Court. It's impolite and draws attention away from the substance of the argument."

Christopher Curran of White & Case on May 26, 2009. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL.

Christopher Curran of White & Case on May 26, 2009. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL.Curran, a veteran appellate advocate, argued on behalf of Sudan once before in the high court. In the case Republic of Sudan v. Harrison, he won an 8-1 decision last March in a dispute over what the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 requires to serve process on a foreign state.

The new case involves the same law and whether it applies retroactively to allow punitive damages awards against foreign states for terrorist actions that occurred before passage of the current version of the law in 2008. Curran won the punitive damages issue in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in July 2017.

Curran laughed at the attention to the word "damn" in a brief phone call Wednesday. "I think the term speaks for itself," he said.

Read more:

Don't Expect Profanities to Fly When Justices Hear 'FUCT' Trademark Case

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Med Mal Defense Win Stands as State Appeals Court Rejects Arguments Over Blocked Cross-Examination

State High Court Reinstates $7M Jury Verdict for Passenger Injured in Potentially Avoidable Crash

4 minute read

Is 1st Circuit the New Center for Trump Policy Challenges?

State Appellate Court Rejects Reasoning for Attorney's Removal From Conservatorship

5 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

- 2California Court Denies Apple's Motion to Strike Allegations in Gender Bias Class Action

- 3US DOJ Threatens to Prosecute Local Officials Who Don't Aid Immigration Enforcement

- 4Kirkland Is Entering a New Market. Will Its Rates Get a Warm Welcome?

- 5African Law Firm Investigated Over ‘AI-Generated’ Case References

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250