10th Circuit Sent Judge Murguia to 'Medical Treatment' After First Sexual Harassment Claim Surfaced in 2016

Chief Circuit Judge Timothy Tymkovich told Carlos Murguia that he wouldn't initiate a formal complaint after the district judge "successfully" underwent the medical treatment.

March 04, 2020 at 01:39 PM

7 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

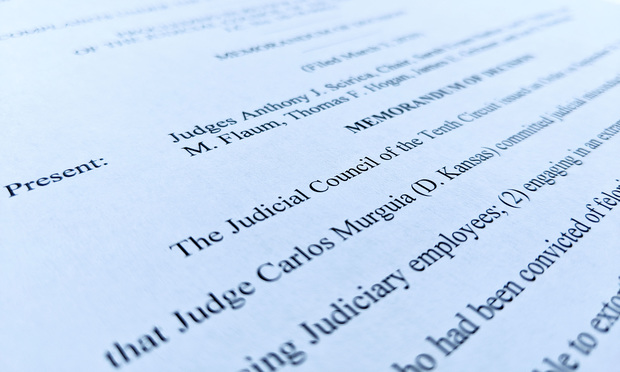

The Committee on Judicial Conduct and Disability of the Judicial Conference of the United States on March 3, 2020, issued a memorandum decision addressing harassment complaints against Judge Carlos Murguia, who has since announced his resignation from the Kansas federal trial bench. Photo: Mike Scarcella/ALM

The Committee on Judicial Conduct and Disability of the Judicial Conference of the United States on March 3, 2020, issued a memorandum decision addressing harassment complaints against Judge Carlos Murguia, who has since announced his resignation from the Kansas federal trial bench. Photo: Mike Scarcella/ALM

The chief judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit declined to initiate a formal sexual harassment complaint in 2017 into then-U.S. District Judge Carlos Murguia after he completed "medical treatment" in response to the claims, according to an order released Tuesday.

The information was revealed by the Judicial Conference's Committee on Judicial Conduct and Disability in an order concluding their probe into Murguia's conduct due to his resignation last month.

The document states that then-Chief Judge for the District of Kansas J. Thomas Marten informed Tenth Circuit Chief Judge Timothy Tymkovich in May 2016 that a former employee had accused Murguia of sexual harassment. Two other district judges had provided that information to Marten after first learning of the alleged harassment in April 2016 from judicial employees.

"The Circuit Chief Judge promptly conducted an informal investigation in accordance with JC&D Rule 53 that included reviewing documentary evidence and confronting Judge Murguia," the order reads, citing a conduct committee rule. "Judge Murguia expressed remorse for his conduct toward the judicial employee who had alleged sexual harassment and agreed to participate in assessment and treatment by a medical professional, at the recommendation of the Tenth Circuit's Certified Medical Professional."

The medical professional, according to Tuesday's order, said after October 2016 that "Murguia had successfully completed treatment." The document does not provide details about the kind of medical treatment he received.

"The Circuit Chief Judge sent Judge Murguia a letter in February 2017 saying that there was credible evidence that he had engaged in misconduct, but that he would not initiate a formal misconduct complaint because of Judge Murguia's apparent honesty in admitting his improper behavior, willingness to correct his behavior, cooperation with the Tenth Circuit's Certified Medical Professional, and successful evaluation and treatment," the order reads.

The order indicates further allegations came to light about Murguia in November 2017, including that he had an extramarital affair with a felon on probation at the time. "These allegations called into question Judge Murguia's candor and truthfulness during the Circuit Chief Judge's previous informal investigation," the document reads.

The circuit court then hired a retired FBI investigator to investigate Murguia further, which uncovered more allegations of misconduct.

"Additional information regarding possible judicial misconduct by Judge Murguia, including his sexual harassment of two additional judicial employees, came to light during this investigation and showed Judge Murguia's lack of candor and truthfulness during the informal investigation, including his lack of candor and truthfulness during his evaluation and treatment following the initial allegations," the order reads.

A representative for the Office of the Circuit Executive for the Tenth Circuit referred comment to the Administrative Office for the Courts, which declined to comment. Tymkovich also deferred to the Administrative Office for comment.

Charles Geyh, a law professor at Indiana University who specializes in judicial ethics, said in the past that he did not think "the federal judiciary regarded sexual harassment of staff as different in kind from other forms of misconduct, which chief judges generally felt could and should best be managed informally first, with the threat of formal discipline held in reserve as a kind of shotgun behind the door if informal efforts failed."

He said other behavior that is also considered a potential violation of the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act, like abusive actions toward lawyers and litigants, may be rooted in problems that could benefit from treatment and that the 2016 process undertaken by Tymkovich was "consistent with past practice."

However, Geyh said the 2017 allegations of sexual harassment against then-Judge Alex Kozinski of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit "represented a pivot point for the federal judiciary—a moment of realization that sexual harassment was a problem too pervasive and too serious to be resolved in the usual way, without new and different protections and procedures in place."

"The early stages illustrate the traditional approach of seeking informal resolution first, followed by escalating sanctions culminating in an impeachment referral. That is a fine approach as a general matter, but when it comes to sexual harassment, this episode reveals a need for near-zero tolerance, to better protect the victims of harassment," Geyh said. "That this judge was allowed to flout the process for four years is unacceptable."

Some, including lawmakers on Capitol Hill, have questioned how Murguia's conduct could have gone on for so long without anyone reporting it.

During a hearing last month on the federal judiciary's budget request, Rep. Norma Torres raised Murguia's case to Administrative Office of the Courts Director James Duff and chair of the Judicial Conference's budget committee, Senior District Judge John Lungstrum, who sat on the same Kansas court as Murguia.

"One of the most troubling things for me is that no one, no one, came forward. The victims were too afraid to come forward," Torres said. "The witnesses that could have potentially come forward on their behalf did not come forward. Other judges that might have been witnesses if they didn't come forward—I have to question whether they were also party to that harassment."

Lungstrum said the conduct had been reported by a court clerk to a judge and that Murguia's conduct was "an absolute shock."

"We have been extremely energetic in our efforts to work with those people who are the victims and those people who remain on Judge Murguia's staff, post his leaving the judiciary," the judge said.

That information from Tuesday's order was not included in a September order from the Tenth Circuit's Judicial Conference, which included Tymkovich, that reprimanded Murguia for his conduct—the most powerful tool in the judicial council's arsenal.

The council then referred Murguia's case to the Judicial Conference's Committee on Conduct and Disability for consideration and potential additional actions against Murguia.

On Tuesday, the committee said its "reviews and deliberations were ongoing" when Murguia submitted a letter to President Donald Trump resigning his commission as a judge.

The order also said that Murguia's "underlying misconduct, as found by the Tenth Circuit Judicial Council, was serious enough to warrant this committee's review to determine whether it should recommend a referral to Congress for its consideration of impeachment."

The last federal judge to be impeached and removed from the bench was District Judge G. Thomas Porteous of the Eastern District of Louisiana in 2010.

Sexual harassment emerged as a growing priority for the judiciary after a wave of allegations were made against Kozinski in 2017, who resigned from his seat over the claims.

Chief Justice John Roberts then directed the creation of a working group focused on judicial misconduct, which has since unveiled a series of reforms.

Congressional testimony from ex-law clerk Olivia Warren last month that alleged repeated harassment by the late Judge Stephen Reinhardt on the Ninth Circuit has put the spotlight back on the judiciary's efforts to address sexual harassment and raised questions about whether the reforms are doing enough to help affected judiciary employees.

Read more:

Former Law Clerk Alleges Repeated Sexual Harassment by Late Judge Stephen Reinhardt

Stunning Reinhardt Sexual Harassment Allegations Prompt Talk of Next Steps on Judicial Misconduct

Kansas Federal Judge Will Resign Amid New Scrutiny of Workplace Harassment Claims

House Questions Effectiveness of Sexual Misconduct Reforms in Wake of Judge's Repeated Harassment

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Zoom Faces Intellectual Property Suit Over AI-Based Augmented Video Conferencing

3 minute read

'A Warning Shot to Board Rooms': DOJ Decision to Fight $14B Tech Merger May Be Bad Omen for Industry

'Incredibly Complicated'? Antitrust Litigators Identify Pros and Cons of Proposed One Agency Act

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250