Does the Am Law 100 Even Matter Right Now?

It's hard not to regard many of our pre-coronavirus concerns as small, trivial and beside the point.

April 23, 2020 at 11:25 AM

4 minute read

The original version of this story was published on The American Lawyer

Workers build an emergency field hospital in Central Park in New York on March 30. Photo: Gabby Jones/Bloomberg.

Workers build an emergency field hospital in Central Park in New York on March 30. Photo: Gabby Jones/Bloomberg.

Editor's note: This column, written in early April, appears in the May issue of The American Lawyer magazine.

I am sitting on my bed in my New York apartment on the Upper West Side struggling mightily to write this column. My editors are getting impatient. But I can barely define a topic, much less zip out a finished draft.

This is why I'm paralyzed: I can't think of a thing to opine about that will have a stitch of urgency a month from now. Today is April 2, and the world is coming apart. So far, more than 2,000 people in New York City have died from the coronavirus, and the White House is projecting 100,000 to 240,000 deaths in the United States before it's all over. And Central Park, which I have the privilege of seeing from my window, is now the site of hospital tents set up in anticipation of a patient overflow. It all looks and feels like a battlefield—but one where the ravages are still unknown.

This is why I'm paralyzed: I can't think of a thing to opine about that will have a stitch of urgency a month from now. Today is April 2, and the world is coming apart. So far, more than 2,000 people in New York City have died from the coronavirus, and the White House is projecting 100,000 to 240,000 deaths in the United States before it's all over. And Central Park, which I have the privilege of seeing from my window, is now the site of hospital tents set up in anticipation of a patient overflow. It all looks and feels like a battlefield—but one where the ravages are still unknown.

By the time you read this, the world will have changed in ways that we can't imagine at the current moment. I don't know which of my friends, family members or colleagues will get COVID-19. I don't know if I will be among those stricken. All I know is that we will hear bad news.

Against this backdrop, it's hard not to regard many of our pre-coronavirus concerns as small, trivial and beside the point. I find that especially true for the sector of the legal profession that I cover—that elite, hyper-competitive world that we call Big Law.

The world of major law firms has always struck me as vainglorious. All that preoccupation with the indicia of achievement—where you went to law school, whether you graded on or wrote onto the law review, whether you clerked for a federal judge, how prestigious your firm is. We've always known deep down that those badges are silly. But now the ridiculousness seems to be in sharp relief.

Ironically, just as the peak of the pandemic is expected to hit, we're unveiling the Am Law 100—that much-ballyhooed annual ranking of America's biggest, most prestigious, most profitable firms. In normal times, that would be the talk of the day.

In any other year, it would seem perfectly normal for the Big Law community to obsess over things like profits per equity partner, revenue per lawyer and all the other measures of a firm's financial success or decline. As watchers of this insular community, we are transfixed by how much partners make and which firms have reached the Super Rich status this year. Each year, you can almost hear the collective gasp that accompanies the list of firms that have reached new heights in PEP. Is it possible that three more firms have surpassed the $4 million PEP mark? Then, there's the schadenfreude about the fallen fortunes of firms that soared too high too fast.

We sift through all the data as if we're searching for oracles. We weigh the numbers, talk about the importance of RPL over PEP, prattle on about "bench strength" and firm strategy—all the usual industry bullshit. As if such things are critical. As if any of us have a clue what we're doing.

It was fun while it lasted, but that game now feels tiresome. So forgive me if I'm at loss for a riveting topic.

Contact Vivia Chen at [email protected]. On Twitter: @lawcareerist

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Change Is Coming in the Trump Era. For Big Law, Change Is Already Here

6 minute read

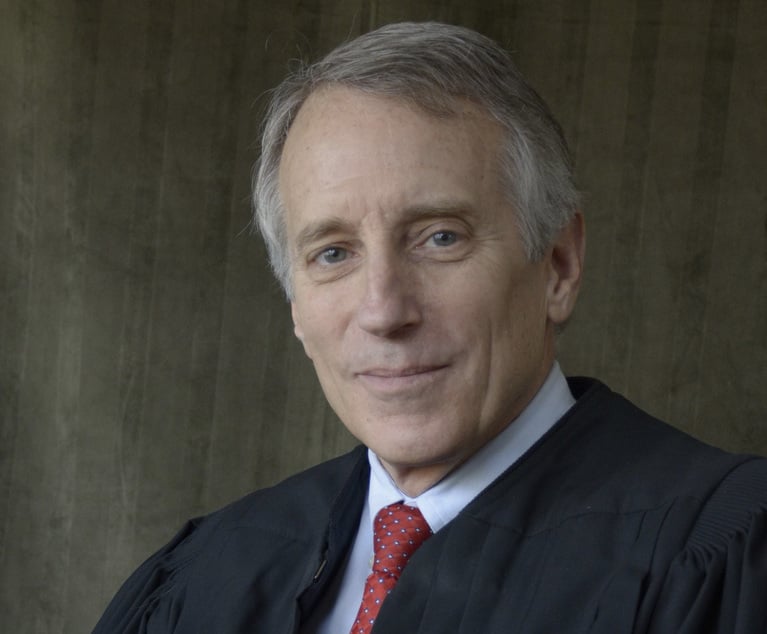

'If the Job Is Better, You Get Better': Chief District Judge Discusses Overcoming Negative Perceptions During Q&A

The Growing Antitrust Scrutiny of DraftKings and FanDuel

Trending Stories

- 1The Rise and Risks of Merchant Cash Advance Debt Relief Companies

- 2Ill. Class Action Claims Cannabis Companies Sell Products with Excessive THC Content

- 3Suboxone MDL Mostly Survives Initial Preemption Challenge

- 4Paul Hastings Hires Music Industry Practice Chair From Willkie in Los Angeles

- 5Global Software Firm Trying to Jump-Start Growth Hands CLO Post to 3-Time Legal Chief

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250