Supreme Court Tears Down Paywall for Georgia's Annotated Codes

The annotations are "government edicts" that can't be copyrighted, even though they are not the law itself and published by a third party, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for a 5-4 majority.

April 27, 2020 at 11:48 AM

5 minute read

The original version of this story was published on Daily Report

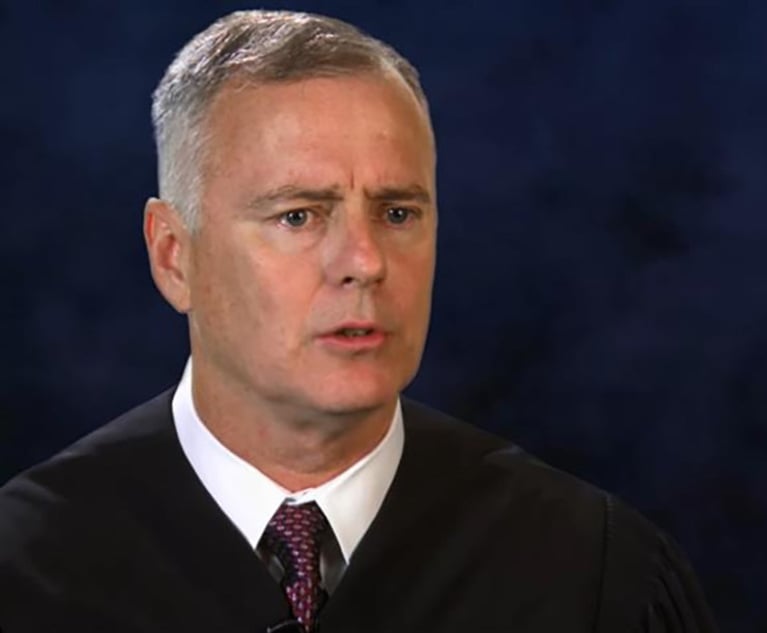

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., U.S. Supreme Court. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM)

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., U.S. Supreme Court. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM)

The state of Georgia cannot copyright the annotations in its official annotated code, the Supreme Court held Monday in a 5-4 opinion.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the court that the so-called government edicts doctrine, which holds that nonbinding, explanatory legal materials created by judges are not copyrightable, also applies to legislative bodies.

"The Court long ago interpreted the word 'author' to exclude officials empowered to speak with the force of law, and Congress has carried that meaning forward in multiple iterations of the Copyright Act," Roberts wrote in Georgia v. Public.Resource.Org.

The Official Code of Georgia Annotated (OCGA) is supervised by Georgia's Code Revision Commission and published under contract to LexisNexis. At least 22 other states have similar arrangements. Georgia argued that the annotations—which include summaries of judicial decisions applying a given provision, attorney general opinions and related law review articles—are not the law itself. By designating LexisNexis' version the official code, the state can make it available for far less, in a $412 bound volume, than competing versions, which can sell for more than $2,000. The state does not publish the annotations online, but nonprofit Public.Resource.Org had been doing so without authorization from the state.

Roberts ruled that, because the commission is "created by the legislature, for the legislature, and consists largely of legislators," and the OCGA is "published under authority of the state," it must be free to all of the public. To rule otherwise would leave citizens, attorneys, nonprofits and private research companies with only "the economy-class version of the Georgia Code available online."

"The animating principle behind this rule is that no one can own the law," Roberts wrote.

Public.Resource.Org founder Carl Malamud said his organization is "looking forward now to getting back to work, making the law more accessible and easier to use."

He said he's grateful to Goldstein & Russell partner Eric Citron, who argued the case, and Elizabeth Rader of Calliope Legal for their pro bono work on the matter, as well as to the many amici curiae who contributed. "This is a testament to the bar and the lawyers who felt it important to stand up for the rule of law," he said.

Vinson & Elkins counsel Joshua Johnson argued for the state of Georgia. Assistant to the Solicitor General Anthony Yang argued for the United States as amicus curiae.

In his opinion, Roberts looked to precedents that held judicial writings are not copyrightable, even if they don't have the force of law, as long as they are created as part of a judge's official duties.

"As every judge learns the hard way, 'comments in [a] dissenting opinion' about legal principles and precedents 'are just that: comments in a dissenting opinion,'" Roberts wrote, quoting a 1980 decision. "Yet such comments are covered by the government edicts doctrine because they come from an official with authority to make and interpret the law."

Roberts indicated that the government edicts doctrine would not apply to non-lawmaking officials, "leaving States free to assert copyright in the vast majority of expressive works they produce, such as those created by their universities, libraries, tourism offices, and so on."

Justices Clarence Thomas and Ruth Bader Ginsburg each issued dissents.

Ginsburg wrote that the government edicts doctrine covers only works created by judges and legislators in the course of their judicial and legislative duties. Georgia had argued that the annotations are copyrightable in part because they're prepared by LexisNexis for the state's Code Revision Commission. Public.Resource.Org violated that copyright when it bought the 186-volume and all of its supplements and made it available for free online, the state argued. "This ruling will likely come as a shock to the 25 other jurisdictions—22 States, 2 Territories, and the District of Columbia—that rely on arrangements similar to Georgia's to produce annotated codes," Thomas wrote. "Perhaps these jurisdictions all overlooked this Court's purportedly clear guidance."

Latham & Watkins partner Andrew Gass, who contributed to an amicus curiae brief on behalf of 15 current and former government officials, said the reasoning of the opinion will likely apply to the executive branch as well and help clear up the occasional copyright dispute that erupts over state agency scientific findings and policy statements. "A broad spectrum of government output is [now] unquestionably free from copyright protection, which is a wonderful result for citizens of a democracy," Gass said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Texas Court Invalidates SEC’s Dealer Rule, Siding with Crypto Advocates

3 minute read

Samsung Flooded With Galaxy Product Patent Lawsuits in Texas Federal Court

GC Conference Takeaways: Picking AI Vendors 'a Bit of a Crap Shoot,' Beware of Internal Investigation 'Scope Creep'

8 minute read

OpenAI, NYTimes Counsel Quarrel Over Erased OpenAI Training Data

Trending Stories

- 1Gibson Dunn Sued By Crypto Client After Lateral Hire Causes Conflict of Interest

- 2Trump's Solicitor General Expected to 'Flip' Prelogar's Positions at Supreme Court

- 3Pharmacy Lawyers See Promise in NY Regulator's Curbs on PBM Industry

- 4Outgoing USPTO Director Kathi Vidal: ‘We All Want the Country to Be in a Better Place’

- 5Supreme Court Will Review Constitutionality Of FCC's Universal Service Fund

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250