In August, the American Bar Association organization responsible for accrediting law schools across the country, known formally as the Council of the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, approved substantial changes to three chapters of its rules for notice and comment [PDF]. Since then, news about the proposed alterations (and academics’ anger at some of them) has intensified, with at least 500 law school professors signing a letter arguing that one of the most controversial measures put forward by the panel—eliminating the standards’ tenure requirement for full-time faculty—would impair academic freedom, particularly for minority instructors.

The purpose of the proposed reforms, according to Am Law Daily sibling publication The National Law Journal, is to encourage more “innovation” among law schools—something many in the legal profession support. For example, in its “Draft Report and Recommendations” [PDF], the ABA’s Task Force on the Future of Legal Education suggests that the current standards be reformed because they “do not encourage innovation, experimentation and cost reduction.” The pertinent question, then, is whether the proposed reforms will accomplish what their authors hope. Although the answer varies depending on the rule being changed, generally it’s negative.

For instance, one reform likely to limit law schools’ educational programs and raise costs is the six-credit hour “experiential course(s)” requirement in proposed Standard 303(a)(3). Law students can satisfy this requirement by taking simulation or clinical courses or by doing field placements. Experiential learning is frequently hailed as a solution to law schools’ problems, but as with New York’s mandatory pro bono requirement, state bar authorities’ reform proposals, and even the president’s widely publicized suggestion that the third year of law school be transformed into a clerking experience, there is no evidence that moving in that direction would lower the cost of legal education or create jobs. As always, the pernicious effects of law school pedigree would most likely determine which students receive the best opportunities, placing schools in an intermediary position that allows them to continue raising costs. (To its credit, the proposed standard’s wording would probably prevent law students from shirking the rule by doing envelope-licking work.)

On the other hand, the proposed rule change with the greatest potential to liberate law schools is simplifying the process for applying for variances from the accreditation standards. Under this proposal, law schools could apply to the council for variances in case of emergencies and in support of their efforts to introduce experimentation in legal education—so long as they meet the standards’ listed requirements.

An imaginative mind can generate some ways to use variances to cut costs: relaxing the full-time faculty office requirement; consolidating or digitizing library resources; or reducing campus space requirements. It’s possible that freestanding private law schools (especially those in the for-profit category) might try to bend the rules. Regardless, these examples of potential variances to the standards would not result in significantly better graduate outcomes or cost reductions; rather, expensive faculty cause law schools’ cost problems.

As mentioned above, the council’s proposals for enabling law schools to experiment with faculty have displeased many law professors. Two proposals to diminish the role of full-time law professors in particular stand out: eliminating the faculty-size rule in covered in Standard 402 and offering two alternatives to the tenure rule contained in Standard 405. Despite the anger, neither change will affect law schools significantly.

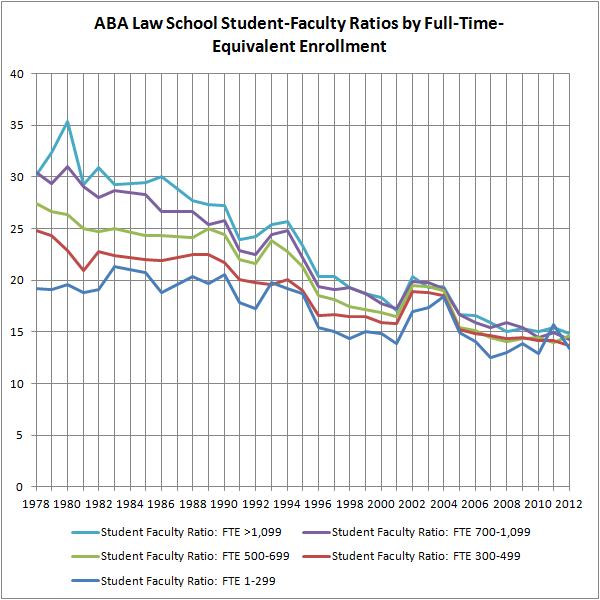

Currently, law schools must maintain a minimum full-time-equivalent-student-to-faculty ratio of at most 30-to-1, though a ratio of less than 20-to-1 is presumed to be in compliance with the rule. According to the NLJ article cited above, the council believes the rule is no longer necessary because so many law schools meet or exceed the ratio requirement. Indeed, the faculty expansion of the last two or so decades is quite evident from the data.

(Source: ABA)

The council justifies axing the ratio rule because it doesn’t account for “important changes in law school curriculum, teaching methodologies and administrative structures in law schools since adoption of [the rules].” One might think this statement indicates that the current rule is holding law schools back, saddling them with tenure-track professors when cheaper, nimbler part-time instructors would be more productive. That’s not so.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law are third party online distributors of the broad collection of current and archived versions of ALM's legal news publications. LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law customers are able to access and use ALM's content, including content from the National Law Journal, The American Lawyer, Legaltech News, The New York Law Journal, and Corporate Counsel, as well as other sources of legal information.

For questions call 1-877-256-2472 or contact us at [email protected]