What the Data on Women Laterals Can Teach About Retention

The lateral partner data show women outpace their brethren at the profession's upper echelons. When women laterals move to the most-profitable Am Law 200 firms, or just to a higher PPP firm, they perform more strongly than their male counterparts.

January 28, 2018 at 06:00 PM

8 minute read

It's perplexing. Women comprise 45 percent of Big Law associates but only 22 percent of partners. Why are they leaving in such numbers? Are they underperforming and thus being outplaced? Are they ineffective at the profession's upper echelons? A comparison of how female and male partners move laterally answers these questions with a resounding “No!” The data show women partners are less likely to depart involuntarily, are more successful when they move to higher profitability firms and are more effective as senior partners.

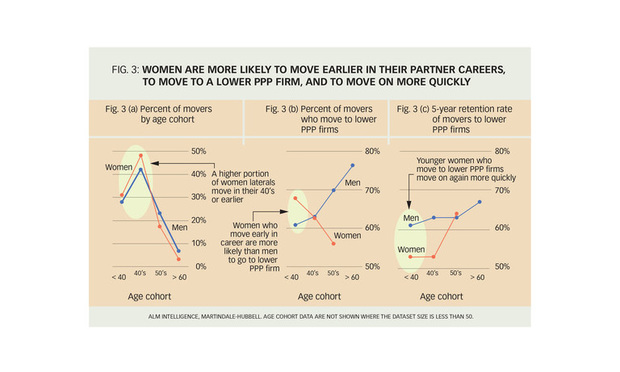

What then gives rise to the dearth of women partners? Our review of the 2,353 partners who moved between the 100 most-profitable firms within the Am Law 200 in 2010 through 2012 provides some insight. These data show that women are more likely to move earlier in their partner careers and to go to lower-profitability firms when they do so. We know from the psychology literature that women exhibit higher risk aversion than men and that this difference is amplified under stress. This yields a hypothesis, consistent with the data, that younger women partners, under the twin stresses of establishing a thriving practice and, in many cases, playing the socio-normative greater role in child rearing, perceive the risks of failing to progress professionally at their current firms as higher than do their brethren. In consequence, they are choosing what they perceive as lower-risk career paths. The implication for firm leaders is that there's enormous partner talent to be harnessed by getting past antiquated ideas that women partners can't perform or don't want to have high-powered careers and instead focusing on how to mitigate the perceived risk of not progressing professionally early in their partner careers.

Let's start with involuntary departures. We know anecdotally that voluntary departures tend to happen earlier in the year (after receipt of the prior year's profit distribution) and that involuntary departures tend to happen later in the year (because departure messages are typically given early in the year, often in connection with compensation, and it takes some months to find a new position). The lateral partner data bear this out: The retention rates at new firms are higher for earlier-in-the-year movers, (Figure 1a), consistent with the notion that later-in-the-year movers contain a disproportionate share of partners who were struggling. Importantly, the lateral data show that women laterals are slightly more likely than their male counterparts to move earlier in the year, (Figure 1b), the opposite of what you would see if women were being outplaced at a higher rate than their male counterparts.

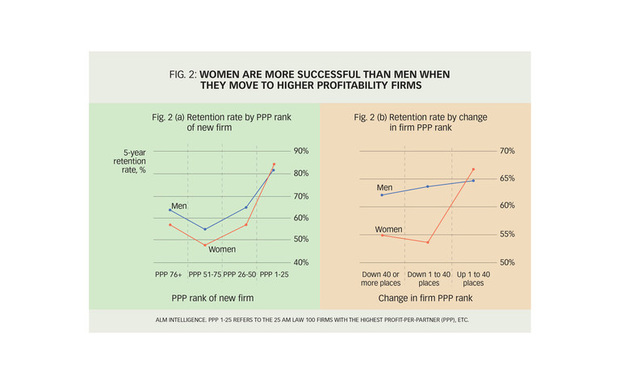

In terms of ability to perform, the lateral partner data show that women outpace their brethren at the profession's upper echelons. When women laterals move to the most-profitable Am Law 200 firms, (Figure 2a) or, indeed, just to a higher PPP firm, (Figure 2b), they perform more strongly than their male counterparts, as indicated by higher five-year retention rates.

The data also suggest women are more successful as senior partners. For laterals who move in their 50s, 44 percent of women move to higher PPP firms, compared with only 30 percent of men—implying that these women are more sought after. This is consonant with the psychology literature which reports that while women and men are far more similar than they are different, there are gender differences centered on women's greater empathy and lower levels of aggression. Such attributes are especially valuable in senior roles and hence would incline women to be more effective.

So, if it's not ability to perform, then what is happening? Well, in addition to leaving voluntarily, the data also show that women leave earlier in their careers than do their male counterparts (Figure 3a) and are more likely to move down in firm PPP level when they do so (Figure 3b). In talking with women who've made such moves, a common theme is management of career risk. There is a sense that, as the demands of playing the socio-normative greater role in child-rearing intensify, there is a heightened risk of failing to progress professionally as they would like. The risks center on things such as failure to be encouraged to serve the clients they'd choose, to be allowed take the roles they'd like with key clients, to be put forth to lead the most important matters and to progress along the compensation ladder. Stepping back to a lower PPP firm is seen as mitigating such risks. Alas, there's a cruel irony here: Retention rates for female partners at their new, lower-PPP firms are significantly lower than for their brethren (Figure 3c)—the risk mitigation isn't happening.

The law firms that first crack the code on retaining women will give themselves a major advantage. Not only will they build a cohort of highly-capable senior partners, but these partners will act as a draw to others, so that the success will compound on itself. There is no one path to cracking the code, but a few elements to consider:

- Cognitive restructuring: Most law firm leaders are past thinking the dearth of women partners has to do with innate ability. But some are still stuck on the idea that it's lack of drive and, even more, that it's a lifestyle preference. Our analysis and consulting suggests a different framing: Many young women partners perceive there to be a high risk of failing to progress professionally as they would like. The psychology literature would support the notion that it's challenging for male firm leaders to appreciate this risk calculus. Hence the need to invest in changing how leaders think of the challenges.

- Male mentoring: We've seen it done successfully—an older male partner takes a younger woman partner under his wing: “I know these are a stressful few years, but I want you to know I'm going to do everything in my power to keep you progressing toward realizing your full potential.” As with so much else in business, it's about the personal connection. With ratios of 4:1 male to female partners it should be possible to find male partners to play these roles.

- Customization through communication: Firms should orchestrate a dialogue to identify ways to mitigate the perceived risks in the context of each firm's business model and culture. This should be a dialogue among all partners, not just women partners and leaders.

About the analysis

We looked at the 2,353 partners who departed from the 100 highest PPP firms within the Am Law 200 between 2010 and 2012. Partners from both U.S. and international offices of these firms were included. We identified the subset of these partners who moved again within five years of their first move using firm websites, press announcements and LinkedIn and profiled these “second moves” by firm type, etc. Partners who moved to firms that later merged are considered not to have moved onward (e.g., Arnold & Porter, Kaye Scholer). Partners at firms that dissolved are considered to have moved (e.g., Bingham McCutcheon).

The tenure of each partner at her new firm is calculated in months starting in the month of the move (i.e., durations at new firms are calculated by partners individually, not grouped by the calendar year of the move. Where the same partner moved twice in the 2010 to 2012 timeframe, s/he is considered as two separate movers). Partners' ages at the time of the move are estimates based on an assumed law school graduation age of 25. We are grateful to ALM Intelligence for access to their lateral partner database.

Hugh A. Simons, Ph.D,. is an ALM Intelligence Fellow. He is a former senior partner, executive committee member and chief financial officer at The Boston Consulting Group and the former chief operating officer at Ropes & Gray. PowerPoint versions of charts available upon request: [email protected]

Paola Cecchi-Dimeglio, J.D., LL.M., Ph.D., is a behavioral economist and chair of the Executive Leadership Research Initiative for Women and Minority Attorneys at the Center on the Legal Profession at Harvard Law School and a senior research fellow at HLS and Harvard Kennedy School. She can be reached at pcecchidimeglio@law.harvard.edu or @HLSPaola.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

How a Paul Weiss Associate’s Career Took Off With Help From a Social Mobility Alliance

6 minute read

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250