Despite Anxiety-Inducing Trends, Am Law 100 Rose to the Challenge in 2017

Last year was one of the best in recent memory for the financial fortunes of the Am Law 100, but few firms are able to rest easily given concerns about the industry's long-term outlook.

April 24, 2018 at 09:52 AM

12 minute read

Credit: Hanna Barczyk

Credit: Hanna Barczyk

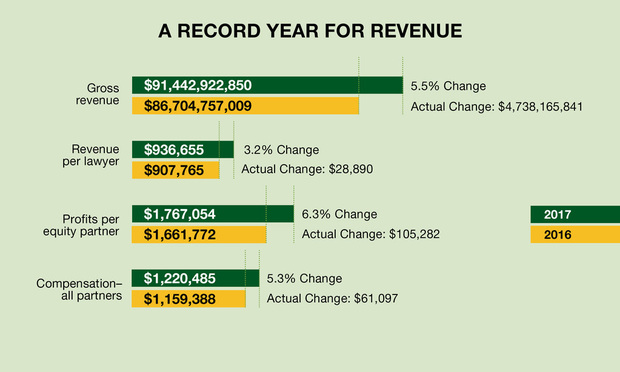

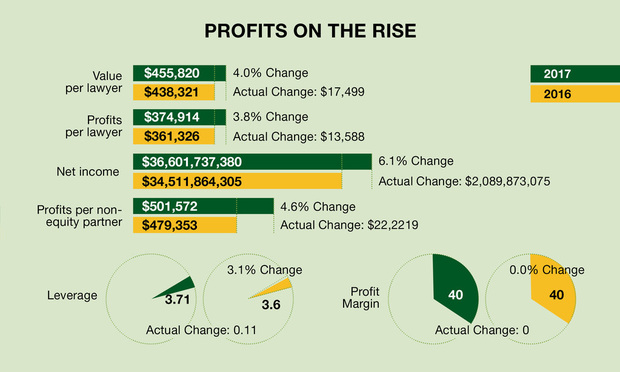

In many respects, 2017 could be considered the Am Law 100's best year since the 2009 recession. Revenue grew at its fastest rate since the big dipper, up 5.5 percent to a record $91.4 billion. Net income—the pool of money firms pay out to their ever-shrinking equity partnership—did even better than the top line, increasing 6.1 percent. That was the second-largest increase since the recession, falling short of only the 7.4 percent increase in net income in 2014.

Looking to buy the report or leverage the Am Law 100 data with powerful data visualizations and expert analysis? Access Premium Content

Looking to buy the report or leverage the Am Law 100 data with powerful data visualizations and expert analysis? Access Premium ContentRevenue per lawyer rose 3.2 percent from last year to $936,655. That came after a year in which RPL, often considered the best barometer of law firm financial health, grew 1.5 percent, causing concern last year that a slowdown was in the offing. Quite the contrary. The Am Law 100 turned in the second-best RPL growth since 2010, behind only the 2014 performance of 3.7 percent growth.

What a year. Right?

These upbeat results come despite long-term trends in the industry that are said to be keeping law firm leaders anxious about the future. They hear clients talk more and more about alternative legal service providers. What's that CLOC thing that happened in Las Vegas? The Big Four are coming. All the while, partners acquiesce to demands for discounts. Realization rates, meanwhile, are far from where they were pre-recession.

So, how to square those trends with one of the most positive years in recent memory? Eric Seeger, a principal at law firm consultancy Altman Weil, says last year indeed provided some positivity for Big Law. Demand rose slightly and firms were able to push through rate increases. As productivity bumped up, those incremental hours went straight to the bottom line, he says. But there are still a number of headwinds. The majority of firms still report to Altman Weil that demand is below pre-recession levels. Celebrating RPL increases of 3.2 percent, Seeger says, is a measure of how far expectations have fallen since the recession.

“The good old days have not returned,” Seeger says. “What we're seeing is firms can squeeze performance gains out of a slight or moderate increase in demand.”

A Year of Uneven Growth

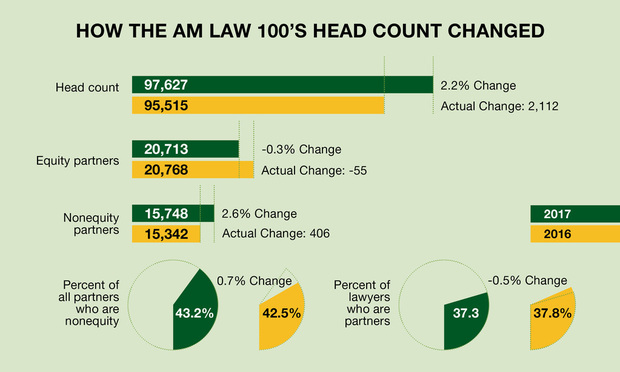

A further peek behind the numbers shows that in 2017 the trend of the biggest, richest firms outperforming their smaller peers accelerated. The largest firms outperformed their smaller competition in both revenue and profit growth. Even so, the smaller firms on the survey fared better than they have in recent years.

One way to see the divergence among the Am Law 100 firms is to group them by quartiles of revenue. The top 10 firms account for a little more than 25 percent of the Am Law 100's revenue. The next 17 firms account for the next 25 percent of revenue. Firms No. 28 thru 53 account for another quarter of the revenue. And the final 47 firms generate the final quarter of Big Law bucks.

How do those groups stack up in terms of growth?

The top 10 firms accounted for 38 percent of the growth in the Am Law 100 last year. The next group, firms 11 through 27, accounted for 25 percent of the growth. The third quartile accounted for 20 percent. And the bottom quartile, nearly half of the firms on the survey, split among themselves just 17 percent of the growth last year. For a plurality of the Am Law 100, it is a daily fight to find growth.

This sort of uneven revenue growth was not apparent in last year's survey.

In last year's survey, revenue was still split evenly (roughly 25 percent) among the same groups of firms: 1 through 10; 11 through 27; 28 through 53; and 54 through 100. But the groups shared an almost perfectly even distribution of the total Am Law growth. The second quartile actually accounted for the most growth—26.8 percent—while the bottom quartile had barely less, 24 percent. The top quartile was responsible for 24.4 percent of the growth.

If you want to see this change using the statistic The American Lawyer has long held out as the best test of law firm financial health, revenue per lawyer, here is average RPL growth from 2017 listed in order for the four quartiles: 4.2 percent; 2.8 percent; 2.3 percent; 2.7 percent. And here is what it was for 2016: 1.5 percent; 3.2 percent; 2.4 percent; 1.7 percent.

And what about profitability?

In a year where average profits per equity partner rose 6.3 percent among the 100 firms, the top 10 firms grew profits per equity partner by 8.4 percent on average. The next group, firms 11 through 27, grew PPP by an average of 5.8 percent. The third quartile, firms 28 through 53, saw PPP increase 5.9 percent on average. The bottom quartile, firms 54 through 100, saw PPP increase 3.4 percent. Take just the 10 largest firms out of the survey, and PPP among the rest of the 90 firms increased 4.6 percent on average.

This sort of uneven profitability growth is more dramatic than the year before.

In 2016, PPP rose by 4.2 percent across the Am Law 100. The first and second quartiles of firms by revenue both increased PPP by an average of 5.6 percent. The third quartile increased PPP by 4.7 percent. The bottom quartile saw a 3.2 percent increase.

“Those firms—the top firms—are really only competing with each other,” says Janet Stanton, a partner at law firm consultancy Adam Smith, Esq. “They are not competing with Axiom. They're not competing with in-house, as the other firms are, which will put pressure on pricing. People go to these top firms, the ones that are pulling away, for the hardest, best stuff. And these firms can attract the best talent as a result. It becomes almost a virtuous cycle.”

The Story Behind Stratification

So what accounts for the acceleration from the pack by the largest firms?

Some of it is due to Norton Rose Fulbright, the 10th-largest firm by revenue in both 2016 and 2017, absorbing Chadbourne & Parke. Assuming the Chadbourne acquisition would have added $230 million to Norton Rose's top line—Chadbourne's last reported revenue figure—the top quartile of firms by revenue last year would have still outgrown their peers. The top 10 firms would still have accounted for about 34 percent of the total growth in the Am Law 100. (The $230 million figure is an estimate to account for the merger, and it is almost certainly a generous one considering Norton Rose added $270 million to its top line last year—which thus assumes the legacy Norton Rose lawyers contributed almost no growth.)

Either way, the story of a distressed law firm's fate resting in the hands of an international giant is a reflection of today's legal market benefiting the biggest firms.

Some of the stratification in this year's survey is also due to a small sample size among the first quartile of firms. There are only 10 of them, and their size means a good or bad year can have an outsize effect on the group's relative performance. DLA Piper is an example of that effect. Last year, it grew revenue by 6.6 percent, or $164 million. That represented 3.7 percent of the Am Law 100's growth on its own. In the prior year, DLA's revenue fell, helping to bring the top 10's share of revenue growth down to earth.

But the bigger story is Kirkland & Ellis. And, to be sure, Latham & Watkins.

Start with Kirkland. It is now the largest firm in the Am Law 100 by revenue. And it accomplished that fact by recording the highest growth rate among any firm in the survey last year: 19.4 percent. Its top-line figure of $3.165 billion is a new record. To put Kirkland's growth into the context of its size, consider this: Last year, it added $514 million in organic revenue growth. That is the equivalent of acquiring Troutman Sanders, the No. 66 firm on the Am Law 100. In one year, Kirkland's revenue growth was greater than the revenue posted by 35 of the 100 largest firms in the country. The Chicago-based law firm, on its own, accounted for 11.6 percent of the Am Law 100's revenue growth last year. In 2016, another year in which Kirkland saw double-digit percentage growth in revenue, the firm was responsible for about 9 percent of the Am Law 100 growth.

Latham has been a similar story in recent years. Like Kirkland, the firm also cracked the $3 billion barrier last year, a first for the Am Law 100. The 8.4 percent revenue growth it enjoyed last year meant the firm added $240 million to its top line, accounting for 5.5 percent of the total growth among firms in the survey. In 2016, that figure was 4.7 percent.

Both firms have benefited from the work their management put in over the past few years recruiting star partners in high-rate practice groups including mergers and acquisitions, private equity and high-stakes litigation. Kirkland's entrée into the world of big-ticket mergers is perhaps the best example of its strategy to target rate-insensitive markets, and it hasn't had a better year than the last. According to data compiled by Mergermarket, Kirkland last year advised on more transactions (489) than any other firm. And it saw the largest increase in the value of the deals it advised on from the previous year, up 63.5 percent in 2017, to $432 billion. Kirkland and Latham rank first and second in the Am Law 100, respectively, and in the number of private equity deals they work on.

But what about the other end of the spectrum?

Among the firms that comprise the bottom quartile of revenue, things were far from bleak. That group of 47 firms had RPL growth and PPP growth last year that outpaced the Am Law 100 in 2016. The vast majority—40 of the 46 firms—saw increases in revenue. On PPP, 37 of the 46 (80 percent) saw gains from last year. The group's arrow is pointing up. But these firms continue to trail the market averages in any given year.

That is in part, again, due to sample size. With 47 firms in the group, it is harder for one or two firms' excellent years to pull up the rest. But it is also due to more firms in the bottom group seeing their revenue shrink—and shrink more—than what is seen among the top firms. The bottom quartile is competing in a more volatile market for legal services.

That is not to say that the bottom quartile was devoid of standout performers. Count the lone newcomer to the Am Law 100 this year, Davis Wright Tremaine, among that group. It saw revenue increase 7.4 percent to $357 million. Profits per partner jumped up 11 percent to $716,000.

Six firms in the group enjoyed double-digit revenue growth: Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton; Fried, Frank, , Harris, Shriver & Jacobson; Cozen O'Connor; Ogletree, Deakins, Nash, Smoak & Stewart; Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel; and Akerman. Combined, those six firms added nearly $300 million to their top line (about $60 million more than Latham & Watkins did, for reference). But almost half of that growth was eaten up by the six firms in the quartile that saw revenue fall last year: Bryan Cave, Locke Lord, Jenner & Block, Crowell & Moring, Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft and Husch Blackwell. In the top group, only Jones Day saw revenue decrease. And that decline was marginal, at less than 1 percent. Of the five bottom-quartile firms that had revenue decreases, two were of nearly 10 percent.

Profitability is even more volatile among the lower-quartile groups. Of the bottom 47 firms, nine saw a decline in PPP, with six of those firms seeing declines greater than 5 percent. Crowell & Moring's PPP declined more than 22 percent; Jenner & Block's, 18 percent. Among the top 10 firms, only one experienced a dip in PPP (again, Jones Day), but it was, again, marginal: 3 percent.

Last year was a positive one for the Am Law 100, make no mistake. But, if you are not at a top firm, don't rest on your laurels. The Big Law market remains hotly competitive for the majority of firms.

Email: [email protected]

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

BCLP Enhances Financial Disputes and Investigations Practice With Baker McKenzie Partner

2 minute read

Quiet Retirement Meets Resounding Win: Quinn Emanuel Name Partner Kathleen Sullivan's Vimeo Victory

Trending Stories

- 1Avantia Publicly Announces Agentic AI Platform Ava

- 2Shifting Sands: May a Court Properly Order the Sale of the Marital Residence During a Divorce’s Pendency?

- 3Joint Custody Awards in New York – The Current Rule

- 4Paul Hastings, Recruiting From Davis Polk, Adds Capital Markets Attorney

- 5Chancery: Common Stock Worthless in 'Jacobson v. Akademos' and Transaction Was Entirely Fair

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250