The Super Rich Are Getting Richer

The richest of the rich continue to prosper and raise profits, a trend that appears to be accelerating as they pull away from the rest of the Am Law 100.

April 24, 2018 at 09:52 AM

9 minute read

Credit: Hanna Barczyk

Credit: Hanna Barczyk

When The American Lawyer first introduced the “super rich” in 2014, the idea was to highlight a club of hyper-performers whose results set them apart from even the other enviably successful law firms in the Am Law 100. We've tracked the group ever since, and last year revised our methodology to take into account the outsized profits being generated at the top of the industry.

Looking to buy the report or leverage the Am Law 100 data with powerful data visualizations and expert analysis? Access Premium Content

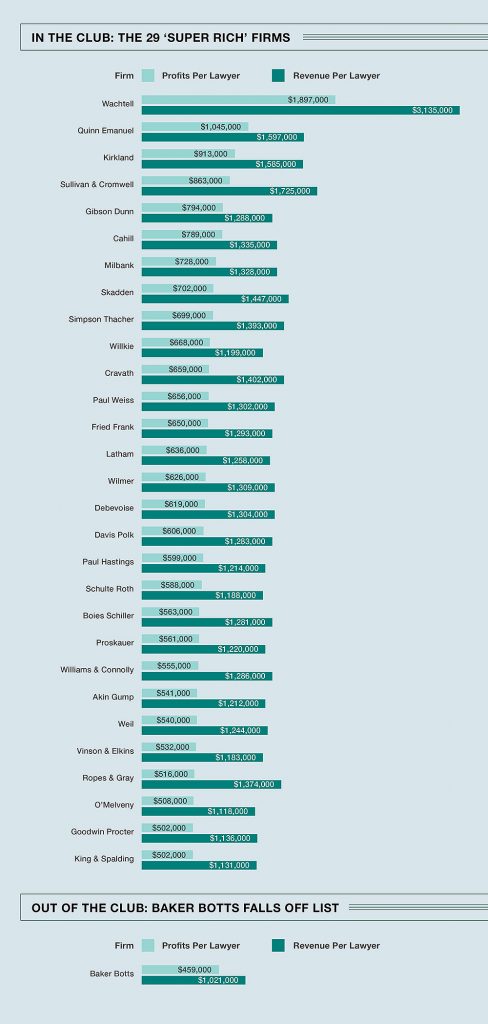

Looking to buy the report or leverage the Am Law 100 data with powerful data visualizations and expert analysis? Access Premium ContentThe revised parameters—at least $500,000 in profits per lawyer and $1.1 million in revenue per lawyer—yielded 29 law firms this year, up from 24 last year. The group includes the usual suspects: counsel to Wall Street banks, private equity firms, hedge funds and multinational corporations. Thirteen of the firms, such as Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz and Debevoise & Plimpton, are based in New York. An equal number, including Kirkland & Ellis and Latham & Watkins, are national. A few are based in other large cities.

Only one firm in last year's club missed the list this year: Houston-based Baker Botts, whose profits per lawyer in 2017 fell 25 percent to $459,000.

The profits per lawyer metric is perhaps the best predictor of super-rich status. Only one firm that had at least $500,000 in profits per lawyer, Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, fell below the threshold for revenue per lawyer.

Six firms joined the super-rich club this year: Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, whose profits per lawyer rose 12.5 percent to $541,000; Weil, Gotshal & Manges, rising 17.6 percent to $540,000; Vinson & Elkins, increasing 11.3 percent to $532,000; Ropes & Gray, up nearly 5 percent to $516,000; Goodwin Procter, up 5.7 percent to $502,000; and King & Spalding, also reaching $502,000 following a 4 percent increase.

But why separate this group from the rest of the Am Law 100? Aside from giving a few firms special bragging rights, what's the point?

Yes, the category shows which partners have gained the most in a year. But the group's movement also underscores a larger trend within the legal industry: increasing stratification. The super rich continue to prosper and raise profits, compared with other merely rich firms. And that trend appears to be accelerating.

In short, the performance gap between the super rich and the rest of the Am Law 100 continues to widen.

The Super Rich Pull Away

Segmentation has reached the point where law firms are not just pursuing different business models but are now engaged in truly different businesses, says Bruce MacEwen of consulting firm Adam Smith Esq.

“The super rich are in the business of being a law firm as we pretty much have already known them: providing advice where money is, if not no object, not much of an object” in bet-the-company litigation and big deals, he says.

Others are in the business of helping clients run their businesses, including some commoditized work. They face pressure to deliver legal services efficiently and at the best possible value for their dollar, MacEwen says.

The profit gap is the result. A decade ago, the average profits per lawyer of these 29 super rich firms was $433,562, while the average profits per lawyer of the rest of the Am Law 100 was $234,075, according to data from ALM Intelligence's Legal Compass. Five years later, in 2012, average profits per lawyer of the same super rich firms rose 24 percent, to $537,225, while the average for everyone else rose 5.4 percent to $246,770.

Five years later, in 2017, average profits per lawyer for the super rich grew 25.8 percent to $675,626, while for everyone else in the Am Law 100 it grew 9.3 percent to $269,770.

In total, over a span of a decade, average profits per lawyer for the super rich firms rose about 56 percent, while rising about 15 percent for the 71 other firms, creating a widening gulf between the firms.

Similarly, revenue per lawyer for the super rich, already much higher, rose at a faster pace over the last 10 years, as the elites pulled away from the pack.

Of course, these are averages among groups, and even some of the super rich firms can see a decline in any given year. Last year, for instance, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan's profits per lawyer fell 7.7 percent to $1,045,000 and Cravath, Swaine & Moore's profits per lawyer dropped 10.3 percent to $659,000.

But the trajectory for this group of firms is clear: Generally, profits are growing at a faster clip than the rest of the Am Law 100.

Will the same thing happen in the next decade?

“The endgame is like the rest of America: the rich are getting richer,” says Bill Henderson, a professor at the Indiana University Maurer School of Law who studies the business of Big Law. Henderson and others say it's likely to continue, pointing to a self-perpetuating cycle.

Without the money to pay superstars, the rest of the firms can't attract the “money-is-no-object matters,” and thus they don't develop a track record, MacEwen says, making it harder to compete for these matters.

“You need to have a seat at the table to get a seat at the table. You can't be on the short list of the AT&T–Time Warner merger,” he says, “unless you've done deals and engagements like that.”

Consider when Amazon.com Inc. announced last June it would buy Whole Foods for $13.7 billion. A bevy of super-rich firms came on board. The grocery chain turned to Wachtell, while the online retailer was advised by Sullivan & Cromwell. Latham & Watkins and Paul Hastings represented the financial advisers in the deal, and the banks providing bridge financing turned to Weil Gotshal.

And when the Justice Department challenged the AT&T merger with Time Warner, the companies tapped litigation and antitrust teams at O'Melveny & Myers, Cravath and Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher.

While belonging to the super-rich club increases the chances of getting retained for the most lucrative matters, some firms outside the list regularly compete for high-end work. For instance, in the largest deal of 2017, when CVS announced it would buy Aetna Inc. for $77 billion, including debt, the drug store chain tapped Shearman & Sterling, Dechert and McDermott Will & Emery, three firms whose revenue per lawyer and profits per lawyer fell below the parameters of the super rich. (Aetna called on Davis Polk & Wardwell.)

'A Slow Decline'?

While the super rich and those just outside the gate are locked in competition with one another for high-profit-margin cases, everyone else is more likely to compete against each other—and with alternative legal service providers and in-house legal departments—for commoditized work.

“The implications are that, certainly, mergers will continue to grow between firms and it may not be out of strength,” says Janet Stanton, also a consultant at Adam Smith Esq., adding that for some firms “there will be a slow decline into irrelevance.”

But Henderson, Stanton and others say that, unlike the growing inequality among citizens in the United States, this is not necessarily a problem for the legal industry. The firms outside the super rich have to adapt to survive.

“A lot of people who are on the short end of the stick don't have any ability to” rise to the top, Stanton says. “That is not the case here. A lot of these law firms make boatloads of money, and it's their own inability or [lack of] willingness to see what needs to be done that is holding them back.”

Firms below the upper echelons of profitability shouldn't try to emulate the super rich or compete with them, but rather work to improve their own business model and innovate, legal industry consultants say. The non-super-rich firms have decades of expertise to sell, and that kind of experience can't be brought in-house, even as the leverage model is diminishing, Henderson says.

“The best thing they have to sell is the 55-year-old and 50-year-old subject-matter expert—they've seen it all—and there's a market for that and it pays well,” Henderson says. “Anything below that specialized work is at risk of going in-house.”

Firms will have to compete by bundling their specialized expertise with improved methods for helping clients keep their businesses running, he says.

“You will have to invest in the systems and approaches that allow you to make decent profits from operational and commoditized work,” Henderson says.

For some firms, this will mean hiring teams of data scientists and pricing experts and using alternative fee structures, project management controls, document automation and other tools to better understand and fix costs to make commoditized work more profitable, Henderson says.

While embracing innovation may cut into partner profits, firms that make marginally better investments than others will survive and will see more lateral candidates, he says.

“A lot of people think this is distressing, but the only thing that is going away are firms that haven't been able to make these investments,” Henderson says. “Good lawyers will not be affected, but some nameplates are going to go away.”

Half of the firms in the Am Law 100 will continue to struggle to grow, he predicts, but the people who work for them will simply move to better firms.

“This is just the market evolving,” Henderson says.

Email: [email protected]

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Are Counsel Ranks Getting 'Squeezed' as Nonequity and Associate Pay Grows?

5 minute read

AI's Place in Big Law Broadens, As Firms Embrace Fresh Uses of the Technology

Trending Stories

- 1With New Civil Jury Selection Rule, Litigants Should Carefully Weigh Waiver Risks

- 2Young Lawyers Become Old(er) Lawyers

- 3Caught In the In Between: A Legal Roadmap for the Sandwich Generation

- 4Top 10 Developments, Lessons, and Reminders of 2024

- 5Gift and Estate Tax Opportunities and Potential Traps in 2025 for Our New York High Net Worth Clients

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250