The Second Hundred Are Being Lapped by the Top Tier

The group as a whole declined in all major metrics, but eight Second Hundred firms had double-digit revenue growth and 22 hit at least 5 percent.

May 22, 2018 at 09:30 AM

14 minute read

Credit: Anna Godeassi

Credit: Anna Godeassi

At first glance, the Am Law Second Hundred firms appear to be the runts of the litter, trailing far behind their Am Law 100 counterparts.

Dive into the Am Law 200 data and personalize it based on your firm, peers and trends. Learn More

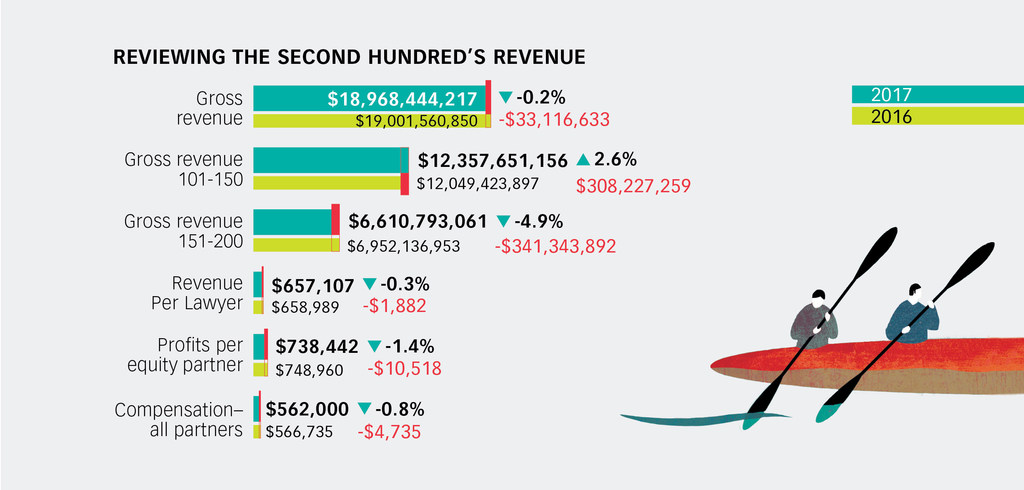

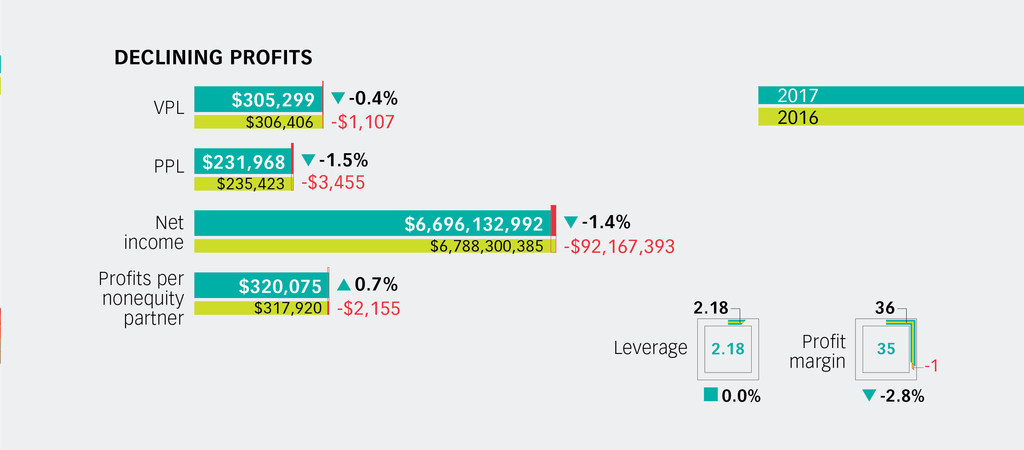

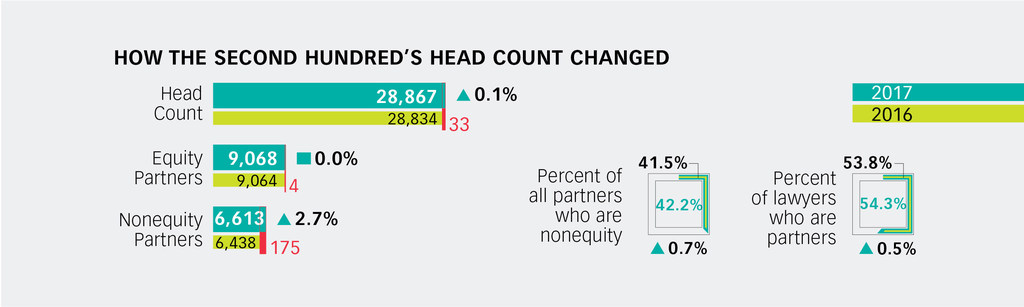

Dive into the Am Law 200 data and personalize it based on your firm, peers and trends. Learn MoreThe disparities between the groups' reported numbers for 2017 are stark: 5.5 percent revenue growth for the Am Law 100 versus a 0.2 percent decline for the Second Hundred; 3.2 percent growth in revenue per lawyer versus a 0.3 percent decline; and 6.3 percent growth in profits per equity partner versus a 1.4 percent decline.

But look closer and a more subtle story emerges that may silence some of the sympathetic sobbing for Second Hundred lawyers. A series of mergers and dissolutions sent some big firms off the list, with the seven firms replacing those slots pulling in almost $400 million less in revenue. Coupled with increased volatility, the shakeups in the Second Hundred paint a somewhat deceptive picture of disappointment and decline following a year in which a large portion of the group actually saw steady progress.

According to both Nicholas Bruch, a senior analyst at ALM Legal Intelligence, and Gretta Rusanow, head of advisory services for Citi Private Bank's Law Firm Group, each of whom spends considerable time reviewing law firm financial results, after peeling back a few layers, the Second Hundred firms' performance doesn't look so bad.

“There is real growth that has occurred,” Rusanow says.

There are 47 firms in the Second Hundred for which Citi has received hard data—the kind law firms give to banks to get loans. After excluding firms that are deemed outliers because, for example, they have made a significant acquisition, revenue for those firms climbed 2.7 percent, which is substantively out of the red, although still about half the growth rate of Citi's sample from the Am Law Top 50 firms, Rusanow says.

For his part, when Bruch interrogates the numbers from the ALM survey, stripping the Second Hundred down to the 94 firms that made the 2017 published list, the average financial performance also improves. Including Pepper Hamilton—a firm that dropped down from the Am Law 100—as the only new entrant and excluding the six firms that made it onto the Second Hundred for the first time, 2017 revenue climbed on average 2 percent, revenue per lawyer rose 1.8 percent, and profits per partner also rose 1.8 percent.

The devil, in this case, lies in the details. The seven firms that dropped off the Second Hundred roster—due to one closing (Sedgwick), four mergers and some usual jostling in the rankings—were replaced by seven firms whose overall revenue was $398 million lower, representing 2.1 percent of the group's total revenue. Kaye Scholer's merger with Am Law 100 firm Arnold & Porter and Sutherland Asbill & Brennan's merger with Global 100 firm Eversheds, for example, took away two of the 10 highest-revenue firms in the Second Hundred. Chadbourne & Parke's merger with Norton Rose Fulbright removed another $232.5 million in revenue from last year's Second Hundred.

“The data doesn't say that all firms are doing poorly,” Bruch says. Indeed, eight of the Second Hundred firms had revenue growth of 10 percent or more and 22 had growth of 5 percent or more, he notes.

“Most companies would like to outpace the economy, and the legal industry is still doing that consistently,” Bruch says. “That's a good story. It's not like things are getting worse for this group. They are just getting better more slowly.”

Bruch is not going full-bore Pollyanna though. A solid 32 members of the Second Hundred saw revenue shrink.

“Many firms did struggle, unquestionably that's true,” Bruch says.

Contracting demand was chief among the reasons that results for the Second Hundred firms were “so much more modest” than the the top-tier firms, Rusanow says. She measures demand for services by a law firm's hours billed. For the Second Hundred, demand contracted 0.9 percent in 2017. The Second Hundred's average hourly rates also rose by a smaller amount (2.3 percent) than those of the Am Law 50 (4.1 percent), Rusanow says.

To help offset soft revenue, Second Hundred firms continued to manage their expenses more closely than any of the other segments, and they also continued to reduce their number of equity partners, Rusanow says.

“This segment of the market is having a very different experience than the Am Law 50, although they are still reporting revenue and profit growth,” Rusanow says.

An Opportunity Now Gone

The numbers demonstrate some industrywide changes.

“There was a time in the wake of the recession where we would have seen a different result,” Rusanow says. “We would have seen work flowing to the Second Hundred.”

Pulling out of the challenging years of 2008 and 2009, clients turned to Second Hundred firms as they grew more price-sensitive, she says. But that's changed.

“This is a market that appears to favor firms that have built a differentiated brand,” Rusanow says.

Kent Zimmermann, a principal of the Zeughauser Group who has represented law firms on merger deals and strategic planning for nearly 10 years, agrees that although positive results exist among the Second Hundred, not everyone is happy.

“I don't want to send the message that everyone in the Second Hundred is screwed, but the ones that are are outperforming are differentiating in terms of specialities or geography,” Zimmermann says. “My take is that many Second Hundred firms are doing as well as firms in the first 100, but not as a group.”

Among the firms that reported double-digit growth in revenue were: San Francisco-based, 662-lawyer Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani; nationally focused 324-lawyer Loeb & Loeb; Philadelphia-based, 375-lawyer Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr; New York-based, 92-lawyer Kobre & Kim; Detroit-based, 403-lawyer Clark Hill; Cleveland-based, 197-lawyer Benesch, Friedlander, Coplan & Aronoff; and San Diego-based, 153-lawyer Procopio, Cory, Hargreaves & Savitch.

What's a common denominator among those winners?

“The firms are being run in a more businesslike way,” says Janet Stanton, a consultant at Adam Smith, Esq.

So what does that mean for lawyers at those firms?

“Less partner autonomy,” says Bruce MacEwen, also at Adam Smith, Esq. “We're often brought in because management knows what to do and the partners don't.”

Dive into the Am Law 200 data and personalize it based on your firm, peers and trends. Learn More

Dive into the Am Law 200 data and personalize it based on your firm, peers and trends. Learn MoreStanton sees the same thing, acknowledging an “increasing chasm” between leadership and partners' understanding of what needs to be done.

Given the firm's financial performance, partners at Kobre & Kim cannot be too worried about autonomy and are probably more gleeful about their bounty. At the New York-based litigation boutique, revenue grew 49 percent to $150.2 million from 2016, when the firm joined the Am Law 200 for the first time. In 2017, Kobre & Kim's profits per partner also soared, jumping 29 percent to $2.49 million. Revenue per lawyer rose a robust 24.8 percent to $1.63 million. During that same time period, the firm's total lawyer head count increased by 19 percent to 92 in 2017.

Benesch also had an impressive year, increasing revenue 21.5 percent to $118.8 million. The firm's management attributes the growth to businesslike strategies—specifically, strategic lateral hiring. In 2017, Benesch made a 15-rung climb in the rankings to 180th place.

“I can talk about our financial performance all day long,” says John Banks, the firm's chief operating officer and chief financial officer. In the past three years, Benesch has grown from 140 to 220 lawyers, he says. Gregg Eisenberg, managing partner and executive committee member, gets credit for having executed that lateral growth strategy, Banks says.

“He's a rainmaker. When he started to lead the firm, he said, 'I'm going to do what I do,' and then he put a lot of time and effort in recruiting,” Banks says.

As a result, the firm has expanded its litigation practice by bringing in partners who brought with them books of business. In exchange, the firm has added associates to help those partners service their clients, Banks says. The firm asks lateral prospects probing questions about their business prior to hiring them and, in return, shares with them the firm's financials and compensation, Banks says.

“We tell them it's a two-way street,” he says. The firm “pays for performance” and “shows people the scoreboard.” Once laterals get there, cross-selling is the watchword.

Gordon Rees, another firm on the list with double-digit revenue growth, also grew by hiring laterals. In 2017 alone, Gordon Rees, which climbed in the rankings from 110 to 103 and saw revenue increase 11.7 percent to $331.2 million, opened nine new offices, in Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio; Milwaukee; Oklahoma City; Omaha and Lincoln, Nebraska; Providence, Rhode Island; Salt Lake City; and Wilmington, Delaware.

“Our expansion's been driven by different factors. There are times when it's client-driven, there are times when it's the market and there are times when it's opportunity-driven,” Gordon Rees managing partner Dion Cominos says. “It's a formula that's worked well for us. We've been very fortunate to have enterprising partners who want to expand in local markets and have done a good job of finding similarly oriented folks.”

'Merger Indigestion'

Hiring laterals is one way to grow, but firms that closed mergers were also among those with the biggest revenue gains in 2017. Saul Ewing merged in September 2017 with Arnstein & Lehr, a midsize Chicago-based firm. The merged firm's revenue increased by more than $66 million, or 43.7 percent, to $219.3 million. Notably, revenue per lawyer dropped 3.5 percent to $585,000 and profits per partner fell 5.1 percent to $555,000, because head count grew.

There is a historical phenomenon that would warn firms against getting merger-happy. Consultant Stanton aptly calls it “merger indigestion.” The term describes firms that have undergone mergers and tend to perform less well than comparable firms that have grown organically.

Bruch has quantified this trend by reviewing 49 mergers between Am Law 200 firms over a 20-year period. He found that the merged firms consistently grew slower than their rivals, with noticeably worse performance in the first three years post-merger. In year one, they lost on average 5 percent of their associates and 6 percent of their partners.

It's obvious to any observer that merger mania has hit the law business. According to Bruch's tallying of mergers that took place in 2015, 2016 and 2017, among Am Law 100 firms there were three deals where a firm absorbed a Second Hundred firm, and 45 where a firm absorbed another outside the Am Law 200.

But among Second Hundred firms, during the same time period, there were about one-third fewer mergers—specifically, 31 deals where a firm absorbed another outside the Am Law 200. (None of the absorbed firms were Am Law 100 firms.)

Although the Second Hundred didn't have as many mergers as the Am Law 100, the group did exceed the top tier in another measure, Bruch says: volatility, or directional change in growth.

Already identified as a pattern among Am Law 100 firms, volatility grew at an even greater pace among Second Hundred firms. In 2016, 29 percent of Second Hundred firms reported a directional change in revenue growth. But in 2017, 36 reported that trend. In comparison, 25 percent of the Am Law 100 reported a directional change in revenue growth in 2016, and in 2017, 19 percent reported that trend.

When it comes to profits per partner, the volatility gap is even starker between the two tiers of firms. In 2017, 37 percent of Am Law 100 firms reported a directional change in profits per partner, compared with 52 percent of Second Hundred firms.

Significantly, among Am Law 100 firms, 53 percent of the firms experiencing volatility in profits per partner went from decline to growth. Among Second Hundred firms, that happened in only 40 percent of cases.

Falling Behind

Which Second Hundred firms lost revenue? Among those that had double-digit dips were 286-lawyer Carlton Fields; 319-lawyer Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle; and 302-lawyer LeClairRyan.

LeClairRyan saw its head count decline 12.9 percent, gross revenue drop 11.2 percent to $142.2 million, and net income fall to $52.5 million, down 6.3 percent. But its revenue per lawyer grew to $471,000, up 1.9 percent, and its profits per partner rose to $423,000, up 11.9 percent. According to data aggregated by ALM Intelligence's Legal Compass, the firm had 47 lateral departures in 2017, and another 20 already in 2018.

But the door is also swinging the other direction: merging and hiring laterals is the LeClairRyan way.

During 2017, LeClairRyan acquired Pizzo & Haman, a multi-office workers' compensation boutique, which included two shareholders, nine senior counsel and three counsel, and built out its aviation liability practice with the addition of nine lawyers from Dentons.

For nearly a decade, the firm has been vacuuming up laterals through mergers, absorbing firms in Houston, New Jersey, New York and its one-time hometown of Richmond, Virginia. In 2016, the firm added seven insurance industry litigators in Boston from Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough. Firm CEO C. Erik Gustafson did not respond to a request to comment for this story.

Shrinking head count and revenue at the same time as growing profitability for equity partners is the goal for some Second Hundred firms, consultant Zimmermann says. If that strategy is executed effectively, “the firms are also growing in depth in certain areas,” Zimmermann says. That's often done by bringing on laterals to bolster certain practice areas and then hiring a deep enough bench of associates for those new rainmakers to expand their books of business.

“A number of Second Hundred firms are performing with strength,” Zimmermann says. “A common thread that runs through them is that they have made choices about what they want to be known for. They are not trying to be all things to all people. After making choices, they build pre-eminence.”

After the recession, Second Hundred firms could initially rely on clients forsaking Am Law 100 firms and coming through their doors prospecting for lower-priced legal services. That's not the case anymore.

“It's not going to be a sustainable strategy to win on price alone—that alone is not a substantial enough differentiator,” Zimmermann says.

The ultimate message from the Am Law 200 numbers may be that firms need to determine why they are valuable to clients and prospects and stick to that profile.

Email: [email protected]

Editor's Note: A previous version of this story mistakenly identified Goldberg Segalla as having engaged in a law firm acquisition. That is not the case. We regret the error.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Are Counsel Ranks Getting 'Squeezed' as Nonequity and Associate Pay Grows?

5 minute read

AI's Place in Big Law Broadens, As Firms Embrace Fresh Uses of the Technology

Trending Stories

- 1With New Civil Jury Selection Rule, Litigants Should Carefully Weigh Waiver Risks

- 2Young Lawyers Become Old(er) Lawyers

- 3Caught In the In Between: A Legal Roadmap for the Sandwich Generation

- 4Top 10 Developments, Lessons, and Reminders of 2024

- 5Gift and Estate Tax Opportunities and Potential Traps in 2025 for Our New York High Net Worth Clients

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250