Outwit, Outplay, Outlast: A Post-Recession View of the Survivors

A decade later, we revisit the 2008 Am Law 200 for a look at how the Big Law game has changed. Spoiler alert: it's gotten much tougher to be a managing partner.

June 20, 2018 at 07:09 PM

15 minute read

The modern American law firm is a beleaguered enterprise, beset on all sides by intensifying competitive pressures both new and old. By all accounts, law firm leaders know this to be a self-evident truth. You see it in your financials, you sense it in the air, and you feel it in your bones. And yet in 69 percent of law firms, partners resist most change efforts . Why the Disconnect? With all respect, we propose skipping the usual detour about the unique challenges of leading change among lawyers. Instead, we posit a more novel theory: survivorship bias. Survivorship bias is the logical error of focusing exclusively on the people that made it past a selection event—and ignoring those who did not. It occurs, at least in part, because the latter group no longer have visibility or voice. And we all fall prey to the availability heuristic : we base our judgments on what comes to mind most easily . It is the combination of survivorships bias and the availability heuristic that shapes the worldview of the working equity partner, creating an effective reality distortion field and presenting seemingly insurmountable communication challenges for most law firm leaders. Partners and Firm Leaders Experience the New Normal (Very) Differently In 2018, Big Law partners look around and see much the same world as they did in 2008. There are still 200 firms in the Am Law 200. The majority of those 200 firms hang on their doors old and prestigious names that are older and more prestigious than ever. In short, they only see the ones who have survived. For the working (read: revenue-generating) equity (read: voting) partner, most of the material changes in the New Normal have remained largely abstract. By and large, Big Law equity partners work and live in 2018 mostly as they did a decade ago: they practice law, they record their time, they try to bill and collect when asked, and they feel their compensation should be higher than it is. Meanwhile, most of the industry-wide response in Big Law after 2008 has placed emphasis on operational discipline, expense control, financial hygiene—and inorganic growth. Executive committees and administrative leaders have strained to cut costs, manage rates and AFAs, field an ever-growing brace of RFP-writing marketers, implement energetic lateral recruitment programs, and vet a constant parade of dance partners for a potentially game-changing combination. It fell to managing partners across Big Law to make difficult and unpopular decisions: to lay off associates and staff, to “manage out” underperforming partners, to spin up de-equitization programs that would help the profit pie split more palatably among the surviving equity partners. You and your peers across the industry have faced down these bruising battles and endured grueling workloads, all to outwit, outplay and outlast the competition, all for the collective good of “the firm.” But this is your day-to-day—neither observed nor experienced by any of your revenue-generating and voting constituency. Equity partners hear that the marketplace is changing ( because you, the managing partner, seem to talk of nothing else ) and yes, they see that some clients are very excited about a new set of buzzwords each year. In practice, most of these transformational changes translates into numberless policies that largely impinge on their time and autonomy: a new way to track billable hours, more rules to manage pricing and billing, a new process to submit expenses, a long list of reasons to adapt to a smaller office, constant pressure to embrace legal technology ( which keeps changing in mystifying ways and takes too much time to learn ), and the list goes on. All these developments have materialized in their lives in a way that is largely disembodied from a market crash that seems very far away now. They are all documented in internal memos ( too long, didn't read ) and delivered in internal meetings ( too busy, didn't attend ). To the working (read: revenue-generating) equity (read: voting) partner, all these distracting annoyances have one other thing in common. They all seem to have originated from or issued by you, the managing partner. Our Collective Memories Need (a Lot of) Help We all remember Dewey and Howrey. Both firms were high-profile and well-respected, their downfalls quick and surprising. The closures of Bingham McCutchen and Sedgwick are remembered because they are recent. But when all is said and done, most equity partners will struggle to name a dozen other law firm failures, and so we tend to think of law firm failures as rare. To be fair, in the grand scheme of things, dissolution is quite uncommon—but in 2018, the curtain call for a prestigious law firm can take many forms. Who remembers McKee Nelson, described by The American Lawyer as “one-of the pre-eminent firms for tax planning and tax litigation”? At its peak in 2006, McKee was a 120-strong firm that eventually whittled down to 30 lawyers by mid-2009 when it was absorbed rather unceremoniously by Bingham McCutchen. If any canonical annals of the history of Big Law existed, they would be peppered with stories of firms much like McKee. In lieu of such a comprehensive document, we revisited the 200 largest firms in America by 2008 revenues to see how they have fared a decade later. To establish a point of comparison, we also analyzed the 1998 class of the Am Law 200 and tracked their progress over the following decade.

The modern American law firm is a beleaguered enterprise, beset on all sides by intensifying competitive pressures both new and old. By all accounts, law firm leaders know this to be a self-evident truth. You see it in your financials, you sense it in the air, and you feel it in your bones. And yet in 69 percent of law firms, partners resist most change efforts . Why the Disconnect? With all respect, we propose skipping the usual detour about the unique challenges of leading change among lawyers. Instead, we posit a more novel theory: survivorship bias. Survivorship bias is the logical error of focusing exclusively on the people that made it past a selection event—and ignoring those who did not. It occurs, at least in part, because the latter group no longer have visibility or voice. And we all fall prey to the availability heuristic : we base our judgments on what comes to mind most easily . It is the combination of survivorships bias and the availability heuristic that shapes the worldview of the working equity partner, creating an effective reality distortion field and presenting seemingly insurmountable communication challenges for most law firm leaders. Partners and Firm Leaders Experience the New Normal (Very) Differently In 2018, Big Law partners look around and see much the same world as they did in 2008. There are still 200 firms in the Am Law 200. The majority of those 200 firms hang on their doors old and prestigious names that are older and more prestigious than ever. In short, they only see the ones who have survived. For the working (read: revenue-generating) equity (read: voting) partner, most of the material changes in the New Normal have remained largely abstract. By and large, Big Law equity partners work and live in 2018 mostly as they did a decade ago: they practice law, they record their time, they try to bill and collect when asked, and they feel their compensation should be higher than it is. Meanwhile, most of the industry-wide response in Big Law after 2008 has placed emphasis on operational discipline, expense control, financial hygiene—and inorganic growth. Executive committees and administrative leaders have strained to cut costs, manage rates and AFAs, field an ever-growing brace of RFP-writing marketers, implement energetic lateral recruitment programs, and vet a constant parade of dance partners for a potentially game-changing combination. It fell to managing partners across Big Law to make difficult and unpopular decisions: to lay off associates and staff, to “manage out” underperforming partners, to spin up de-equitization programs that would help the profit pie split more palatably among the surviving equity partners. You and your peers across the industry have faced down these bruising battles and endured grueling workloads, all to outwit, outplay and outlast the competition, all for the collective good of “the firm.” But this is your day-to-day—neither observed nor experienced by any of your revenue-generating and voting constituency. Equity partners hear that the marketplace is changing ( because you, the managing partner, seem to talk of nothing else ) and yes, they see that some clients are very excited about a new set of buzzwords each year. In practice, most of these transformational changes translates into numberless policies that largely impinge on their time and autonomy: a new way to track billable hours, more rules to manage pricing and billing, a new process to submit expenses, a long list of reasons to adapt to a smaller office, constant pressure to embrace legal technology ( which keeps changing in mystifying ways and takes too much time to learn ), and the list goes on. All these developments have materialized in their lives in a way that is largely disembodied from a market crash that seems very far away now. They are all documented in internal memos ( too long, didn't read ) and delivered in internal meetings ( too busy, didn't attend ). To the working (read: revenue-generating) equity (read: voting) partner, all these distracting annoyances have one other thing in common. They all seem to have originated from or issued by you, the managing partner. Our Collective Memories Need (a Lot of) Help We all remember Dewey and Howrey. Both firms were high-profile and well-respected, their downfalls quick and surprising. The closures of Bingham McCutchen and Sedgwick are remembered because they are recent. But when all is said and done, most equity partners will struggle to name a dozen other law firm failures, and so we tend to think of law firm failures as rare. To be fair, in the grand scheme of things, dissolution is quite uncommon—but in 2018, the curtain call for a prestigious law firm can take many forms. Who remembers McKee Nelson, described by The American Lawyer as “one-of the pre-eminent firms for tax planning and tax litigation”? At its peak in 2006, McKee was a 120-strong firm that eventually whittled down to 30 lawyers by mid-2009 when it was absorbed rather unceremoniously by Bingham McCutchen. If any canonical annals of the history of Big Law existed, they would be peppered with stories of firms much like McKee. In lieu of such a comprehensive document, we revisited the 200 largest firms in America by 2008 revenues to see how they have fared a decade later. To establish a point of comparison, we also analyzed the 1998 class of the Am Law 200 and tracked their progress over the following decade.  Our analysis surfaced the following 4 trends:

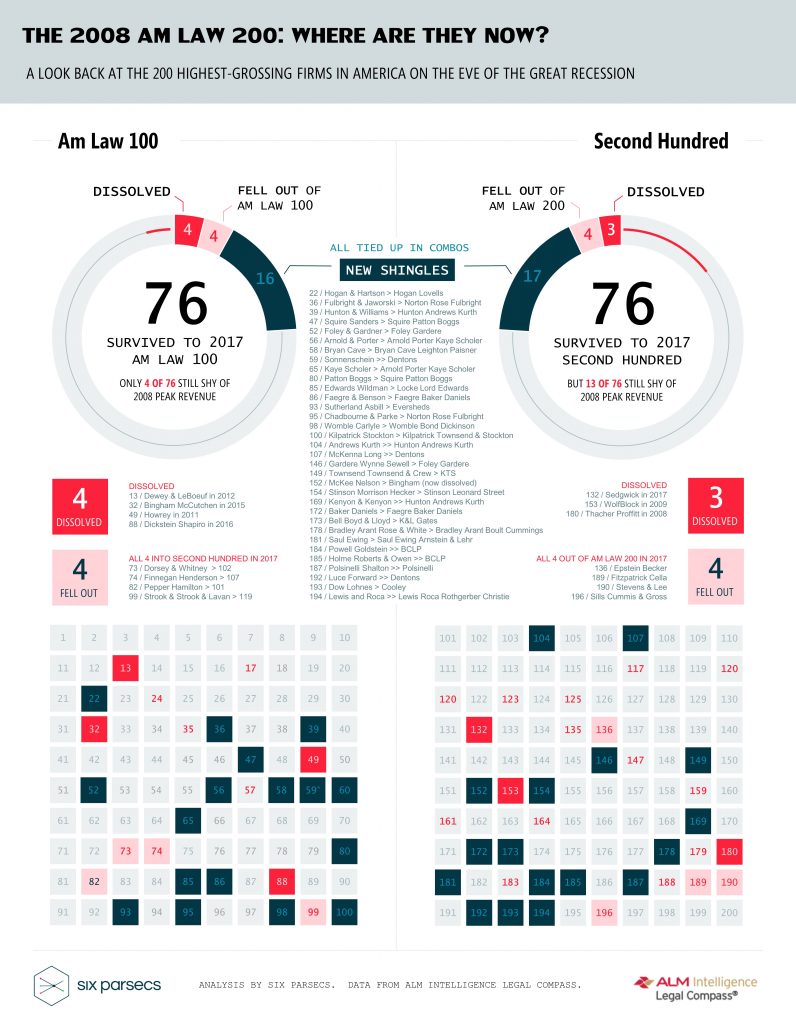

Our analysis surfaced the following 4 trends: - Large law firms are relatively resilient. Relative to corporate America, a 76 percent survival rate over a decade is still fairly cushy. For context, the 20-year survival rate for the Fortune 500 is an unforgiving 38 percent, while roughly 60 percent of the 1998 class of the Am Law 200 made it into the 2017 rankings with their shingles intact. This is, however, cold comfort for many of the firms that haven't yet managed to recapture the prosperity of the pre-recession years.

- The stakes got much higher post-recession. Of the 1998 Am Law 200, nine firms disbanded over the following decade while 24 firms had merged into new shingles by 2007. While those numbers don't seem too different from the track record of the 2008 class, the difference lies in the size and scale of firms involved.

- A few megafirms emerged from daisy-chained mergers and serial acquirers. Like firm failures, mergers got grander in scale after 2008—but this happened more gradually in tandem with the progression of combinations.

- Combined firms are invading the upper reaches. Norton Rose Fulbright made its debut into the Am Law rankings in 2013 by posting $1.9 billion in gross revenues—one of only 24 firms in the 3-comma-club that year. The combinations of Squire Sanders with Patton Boggs as well as Arnold & Porter with Kaye Scholer vaulted the newly shingled firms into the Am Law 50; the same will be true of Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner and Hunton Andrews Kurth next year.

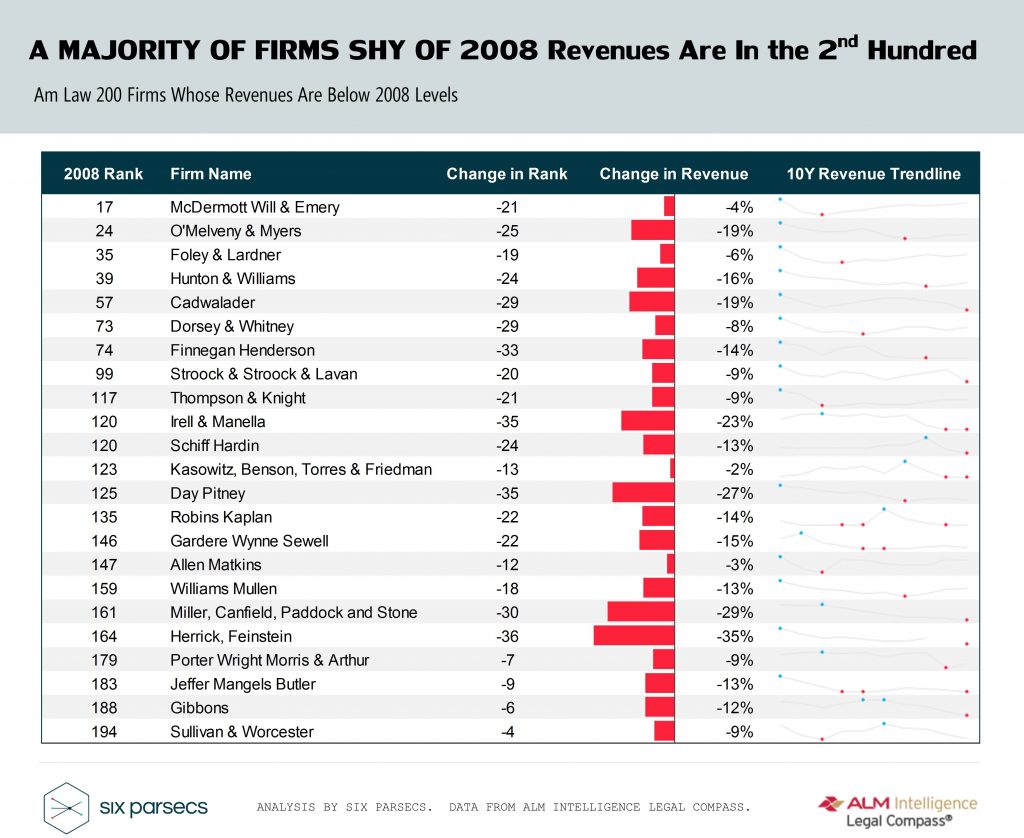

Aggregate market-level analyses often show the Am Law 100 outperforming the Second Hundred. From 2008 to 2017, the U.S. Census estimates 18 percent growth in revenue for legal services sector. From the 2008 Am Law 100, 61 firms managed to outpace the industry in revenue growth, while only 51 of the 2008 Second Hundred firms managed the same feat. Taken out of context, these statistics fuel the mistaken notion that size can provide sufficient competitive advantage—a common but dangerous strategy trap. The New Normal, in One Picture To say that demand is flat is intrinsically abstract. Most equity partners understand the academic concept of supply and demand, and it is galactically obvious to all concerned parties that flat demand is worse than growing demand. What is less obvious is how flat demand practically affects the business of the modern law firm. For managing partners struggling to communicate the extent of structural changes in the legal marketplace—or the challenges they imply for Am Law 200 firms wishing to remain so hereafter—we provide a visual aid.

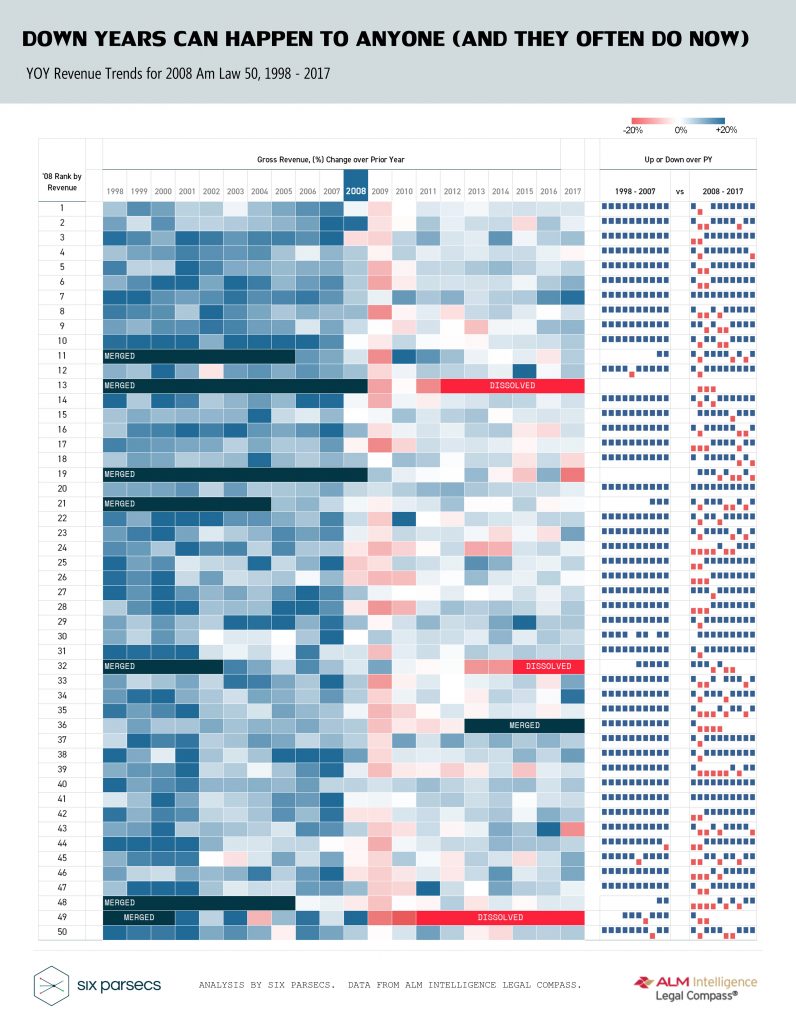

Aggregate market-level analyses often show the Am Law 100 outperforming the Second Hundred. From 2008 to 2017, the U.S. Census estimates 18 percent growth in revenue for legal services sector. From the 2008 Am Law 100, 61 firms managed to outpace the industry in revenue growth, while only 51 of the 2008 Second Hundred firms managed the same feat. Taken out of context, these statistics fuel the mistaken notion that size can provide sufficient competitive advantage—a common but dangerous strategy trap. The New Normal, in One Picture To say that demand is flat is intrinsically abstract. Most equity partners understand the academic concept of supply and demand, and it is galactically obvious to all concerned parties that flat demand is worse than growing demand. What is less obvious is how flat demand practically affects the business of the modern law firm. For managing partners struggling to communicate the extent of structural changes in the legal marketplace—or the challenges they imply for Am Law 200 firms wishing to remain so hereafter—we provide a visual aid.  The above highlight table shows the YOY revenue changes for the 2008 Am Law 50. Firm names and actual percentage figures have been omitted to emphasize the drastic, structural change wrought by the Great Recession. In particular, the final pair of columns on the right paint a fairly clear picture of how much tougher the Big Law game has become in the last decade. In the decade prior to the subprime meltdown, Am Law firms did not have down years, particularly in the upper echelons. It just did not happen because the industry-wide demand growth was that good . This is no longer the reality we occupy. Am Law 200 firms now compete in an environment of ever-present demand volatility and unprecedented margin pressure. Down years can happen to any firm—regardless of size. In a largely flat market, most law firms are finding that it is now stunningly, unbelievably difficult to acquire new revenue organically. This is at least in part why firms remain so dependent on inorganic growth. The bargaining power of clients is already quite high due to the perennial cost pressures placed on corporate law departments. While the insourcing trend may be nearing its natural peak, client pressure to step up solution-orientation, client service, and pricing sophistication are likely to further intensify in tandem with the continuing maturation of the legal operations function . Meanwhile, bargaining power of talent is on the rise . Associate compensation is on the agenda yet again, and the perennially frothy lateral market chips away slowly but surely at the stability of the partnership structure. Other existential threats, albeit more remote, loom on the horizon as the Big 4 , ALSPs and legal tech companies probe for an opening to shave away precious market share from incumbent law firms. Playing for size won't be enough to defend against these threats. The firms hoping to survive—or perhaps even thrive—to see their shingles make it intact into the 2027 Am Law 200 must compete more intensely, think more creatively, and act more decisively than ever before. Notes on Data Reliability Since data reliability is an ever-present issue in legal market analysis, we append a few notes. The tie-ups noted here are limited to new shingles. This leaves out of the analysis those survivors who relied upon less visible means of inorganic growth, including aggressive recruitment of lateral talent, and acquisitions of operations too small to make the Am Law 200 cut. A review of merger data over a similar period suggests that the snapshot of the Am Law 200 is far more likely to understate (rather than overstate) the overall level of reliance on inorganic growth. From 2007 to 2016, Altman Weil Mergerline reported 688 law firm combinations, with 89 percent of them classified as acquisitions rather than “true mergers,” defined as a combination in which the larger firm is no more than twice the size of the smaller. Of all acquisitions, 78 percent of combinations involved lateral groups of 2 to 20 lawyers. Most of these deals occur outside of the Am Law 200. While those omissions mean that this snapshot does not represent a comprehensive representation of the entire legal services market, the discernible trends here are still significant and meaningful for the segment covered in the analysis. Jae Um is founder and executive director of Six Parsecs. She is an ALM Intelligence Fellow.

The above highlight table shows the YOY revenue changes for the 2008 Am Law 50. Firm names and actual percentage figures have been omitted to emphasize the drastic, structural change wrought by the Great Recession. In particular, the final pair of columns on the right paint a fairly clear picture of how much tougher the Big Law game has become in the last decade. In the decade prior to the subprime meltdown, Am Law firms did not have down years, particularly in the upper echelons. It just did not happen because the industry-wide demand growth was that good . This is no longer the reality we occupy. Am Law 200 firms now compete in an environment of ever-present demand volatility and unprecedented margin pressure. Down years can happen to any firm—regardless of size. In a largely flat market, most law firms are finding that it is now stunningly, unbelievably difficult to acquire new revenue organically. This is at least in part why firms remain so dependent on inorganic growth. The bargaining power of clients is already quite high due to the perennial cost pressures placed on corporate law departments. While the insourcing trend may be nearing its natural peak, client pressure to step up solution-orientation, client service, and pricing sophistication are likely to further intensify in tandem with the continuing maturation of the legal operations function . Meanwhile, bargaining power of talent is on the rise . Associate compensation is on the agenda yet again, and the perennially frothy lateral market chips away slowly but surely at the stability of the partnership structure. Other existential threats, albeit more remote, loom on the horizon as the Big 4 , ALSPs and legal tech companies probe for an opening to shave away precious market share from incumbent law firms. Playing for size won't be enough to defend against these threats. The firms hoping to survive—or perhaps even thrive—to see their shingles make it intact into the 2027 Am Law 200 must compete more intensely, think more creatively, and act more decisively than ever before. Notes on Data Reliability Since data reliability is an ever-present issue in legal market analysis, we append a few notes. The tie-ups noted here are limited to new shingles. This leaves out of the analysis those survivors who relied upon less visible means of inorganic growth, including aggressive recruitment of lateral talent, and acquisitions of operations too small to make the Am Law 200 cut. A review of merger data over a similar period suggests that the snapshot of the Am Law 200 is far more likely to understate (rather than overstate) the overall level of reliance on inorganic growth. From 2007 to 2016, Altman Weil Mergerline reported 688 law firm combinations, with 89 percent of them classified as acquisitions rather than “true mergers,” defined as a combination in which the larger firm is no more than twice the size of the smaller. Of all acquisitions, 78 percent of combinations involved lateral groups of 2 to 20 lawyers. Most of these deals occur outside of the Am Law 200. While those omissions mean that this snapshot does not represent a comprehensive representation of the entire legal services market, the discernible trends here are still significant and meaningful for the segment covered in the analysis. Jae Um is founder and executive director of Six Parsecs. She is an ALM Intelligence Fellow.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Strategic Pricing: Setting the Billable Hour at the Intersection of Psychology, Feedback and Growth

'Rethink Everything' or 'Optimize What's Working'? The Right Law Firm Strategy

7 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Silk Road Founder Ross Ulbricht Has New York Sentence Pardoned by Trump

- 2Settlement Allows Spouses of U.S. Citizens to Reopen Removal Proceedings

- 3CFPB Resolves Flurry of Enforcement Actions in Biden's Final Week

- 4Judge Orders SoCal Edison to Preserve Evidence Relating to Los Angeles Wildfires

- 5Legal Community Luminaries Honored at New York State Bar Association’s Annual Meeting

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250