Why the GC of Molson Coors Is Moving Major Work From Prestigious New York Firms

The belief that top lawyers are only found in the largest cities is growing increasingly outdated.

December 24, 2018 at 04:56 PM

7 minute read

Denver, Colorado.

Denver, Colorado.

Last year, we found ourselves in a significant arbitration. It was the largest adversarial dispute we have faced in my eight-year tenure with Molson Coors. We were pitted against a fabled New York law firm—one of the five most highly regarded firms in the nation. We considered hiring an equally pedigreed firm in a money-center city to represent us, but we wanted to find the very best lawyers for this matter, anywhere in the country.

I thought of that arbitration (which I'll come back to shortly) when reading AdvanceLaw's recent article about the relationship between law firm performance and city size. To be clear, they were not looking at lawyers in small cities; they were looking at the performance of lawyers across 40 major cities, where there was enough data to draw meaningful comparisons.

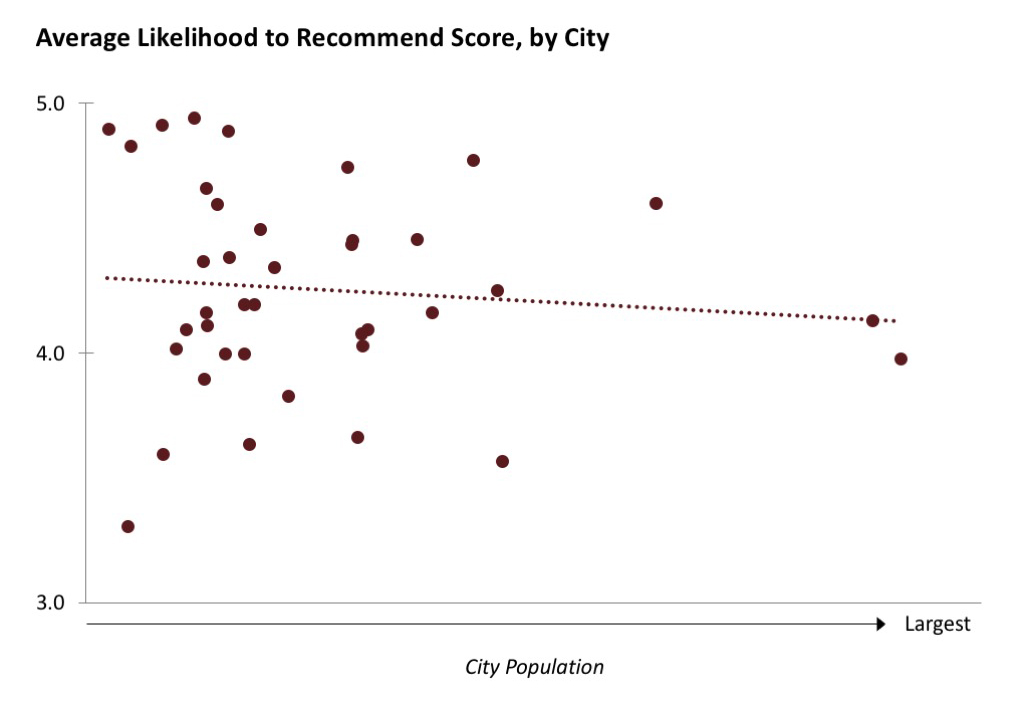

The key finding is represented in the graphic below—showing that, on average, firms in reasonably large cities (like Seattle, St. Louis, Minneapolis, Denver and Atlanta) perform just as well as or better than firms in the largest, most expensive cities (such as New York and Los Angeles).

The article's authors suggest that “top talent is increasingly dispersed,” and that clients should “resist defaulting to the usual locations out of history or habit.”

The GCs I know all make counsel selection decisions, like the one we faced, on some combination of gut feeling and prior experience. But many of us want more certainty. As Bill Deckelman's piece on Am Law 20 firms' performance noted, “We're in a market where the law firms that are the most lauded and receive the lion's share of important work perform—on average—worse than competitor firms on everything that clients care about. What is going on here?”

This, by the way, is what I and 200 other GCs are up to with AdvanceLaw—we've created a market where the best lawyers and firms are getting a growing share of our legal work.

In our recent arbitration, we ended up choosing lawyers from the Denver office of a historically Philadelphia-based firm. Given the brand-name firm representing our opponent, and the unwritten rule that we needed diplomatic parity with their law firm, the easy decision would have been to hire an especially credentialed firm based in a city like New York. And by doing so, we might be slightly more insulated from criticism should things go poorly in a case that our board was closely watching.

Unfortunately, this is what keeps the profession from improving—choosing lawyers based on the historical reputation of the law firm and its geographic location, even in the face of a better option. But we didn't do that, and we needed our lawyers to be excellent on this major matter.

And they were. In my view, our Denver counsel out-lawyered the blue-chip New York law firm's larger team, and we were very happy with the result. (By the way, the AdvanceLaw-vetted firm we retained for this was Ballard Spahr, a 700-lawyer firm with offices across the country. Part of the magic here is that “smaller city” doesn't have to equate to “smaller firm.”)

Of course, I am not condemning any particular lawyer, firm or city. But the traditional bias in favor of law firms in the largest cities needs to be re-evaluated. The research suggests that perhaps our bias should be the other way—there are elite lawyers across the country, in many cases at a lower price point.

We routinely retain counsel in major financial or regulatory centers when there is a specific skill and experience only they can supply. Increasingly, however, we find ourselves relying on lawyers and firms in other cities for the rest of our work.

In our experience, there is a lot of untapped talent able to take on high-stakes and national work in the cities mentioned above, as well as in Milwaukee, Charlotte, Cleveland, Phoenix, Kansas City, Indianapolis and beyond. The United States has an abundant supply of sophisticated lawyers.

So why do GCs still tend to disproportionately hire firms in the very largest of American cities? A couple possibilities come to mind.

First, the biggest cities offered much more depth on corporate matters a few decades ago, meaning that even today some senior lawyers and corporate directors still associate the best legal work with the largest cities. But in my view, things have changed. Over the last 20 years, there has been a major migration of talent from money-center cities—many great lawyers have moved to places like Denver.

And given the choice, who wouldn't move to Denver? I say this partly in jest—it's the move I made early in my career—but if sophisticated legal work is available, the pay is good, the cost of living is lower, and the unsurpassed mountain views and great beer are still here, it's not really a hardship.

Not every elite lawyer wants to work in the kind of environment that yields $3 million in profits per partner, especially when the alternative for senior partners is often $1 million or more in several mid-to-large cities across the country. It's also a far easier decision than it would have been in 1980, or even 2000. Work is more mobile, technology has advanced, communication is fluid, and paper files no longer keep lawyers tied to a specific physical office.

So, in ways that may not have previously been possible or professionally acceptable, we may have hit an economic tipping point where it's more rational for high-performing lawyers to give up the trappings of the money centers and move to other cities or return back to where they were raised.

And because clients can efficiently retain a Denver, Seattle or Minneapolis office for national work, the demand for those lawyers should continue to grow. The calculus has shifted. It's good for these law firms, and clients like us are reaping the benefits.

A second point is that the largest cities still tend to breed lawyers with deep specialties, and clients will inevitably need that expertise at some point. That specialty is often financial or regulatory in nature. But the problem—and it has happened to us, too—is that when new work unrelated to that narrow expertise pops up, many clients keep sending work to those same firms, further entrenching these relationships. Sure, it's easier to do that, but that won't always generate the best results.

Clients often say they only use money-center firms on occasion, but those firms' revenues tell another story. The numbers are mostly achieved with a steady stream of client matters placed into sizeable staffing pyramids—lawyers you've never met billing hundreds of hours to a file. This staffing model is a major source of frustration among GCs with whom I speak, and is consistent with the Thought Leaders research showing that some of the largest and most-pedigreed firms fail to outperform the rest.

Related to all this is that law firms headquartered in places like St. Louis, Cleveland and Seattle have been expanding into cities like New York and San Francisco, bringing with them lower costs, flatter staffing, and more-attractive pricing. This is a positioning advantage. They operate and act with the efficiencies of a mid-market shop but have the physical presence and capabilities of a firm headquartered in these cities. This is an advantageous move for the firms and their clients.

At the end of the day, what we like most about firms outside the traditional mega-cities isn't cost, but quality, responsiveness, innovativeness and efficiency. Cost matters, but as with great beer, quality matters even more.

So for me, the major and most welcome surprise coming out of the Thought Leaders research is the notion that it's not just cost savings but better quality that can be had when migrating high-stakes work from the usual suspects. To paraphrase something AdvanceLaw recently noted, the blue-chip firms of the past are not necessarily the same as the blue-chip firms of the future.

Lee Reichert is the chief legal and corporate affairs officer of Molson Coors Brewing Co.

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Alston & Bird Adds M&A, Private Equity Team From McDermott in New York

4 minute read

Veteran Federal Trade Law Enforcer Joins King & Spalding in Washington

4 minute read

Houston Trial Lawyer Mary-Olga Lovett Leaves King & Spalding to Open Boutique

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250