Lifetime Achiever: Richard Riley, Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough

Richard Riley, the former South Carolina governor and education secretary under President Clinton, has given his career to advancing children's education.

August 22, 2018 at 06:00 AM

4 minute read

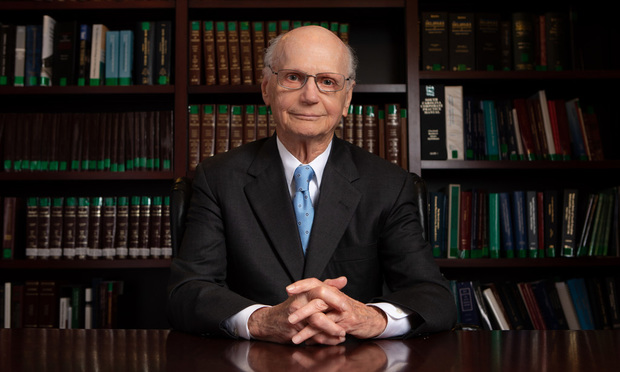

Nelson Mullins senior partner Richard Riley. Photo: Forrest Briggs.

Nelson Mullins senior partner Richard Riley. Photo: Forrest Briggs.

South Carolina's motto, dum spiro spero, means “while I breathe, I hope.” It could be Dick Riley's motto as well.

Growing up, Riley always knew he'd be a lawyer. South Carolina in the mid-1950s was still a racially segregated, educational backwater, and he decided to use the law to improve education.

“We were at the bottom of the sack in education in everything,” Riley says. “I was determined to make South Carolina a leader.”

Riley, who is now 85 and a senior partner of Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough, was elected to the South Carolina legislature in 1963, soon after he joined his father and brother's law practice in Greenville. After 14 years as a progressive reformer, he was elected governor in 1978.

Voters amended the state constitution so he could run for a second term, and he won in a landslide.

It took a tenacious grassroots campaign for Riley to pass the sweeping reforms of the Education Improvement Act in 1984. It allocated $219 million for 61 initiatives to raise standards; reduce class sizes; add early childhood programs, remedial and advanced classes; and increase teacher pay.

The legislation was funded by a penny sales tax that took a statewide “people power” movement to pass, featuring public forums that attracted thousands of South Carolinians.

“We got the public involved and finally forced the legislature to get behind it,” Riley says. His team won buy-in from business leaders seeking to attract new industry, as well as teachers, school administrators and parents.

“It's bottom-up and top-down reform,” says Terry Peterson, Riley's educational adviser since his days as governor. “You need good policy and funding, but you've got to get the people on the ground excited about good education—and give them the tools.”

Riley joined South Carolina's biggest firm, Nelson Mullins, after leaving office. He went to Washington, D.C., in 1993 to head up staffing for President Bill Clinton's Cabinet-level departments, and Clinton then made him secretary of education. He turned down Clinton's subsequent offer of a Supreme Court appointment.

“I was in love with what I was doing,” he says. “It was what I'd aspired to all my life. In Washington, with my key officers, I could make decisions that impacted 50 million children.”

As education secretary, Riley used the same progressive yet pragmatic tactics to encourage states to improve teaching and learning standards. His legacies include after-school learning centers for low-income children, internet access for all schools, and expanded grants and loans for college.

In South Carolina, the educational advances Riley championed have lost ground as subsequent administrations diverted funds from the penny tax. But Riley remains upbeat, energetic and as busy as ever.

He's working through EducationCounsel, a Nelson Mullins consultancy, and the Richard W. Riley Institute at Furman University for new education advances. The Riley Institute has partnered with California's pioneering New Tech Network to win a federal grant for 13 pilot schools in rural South Carolina towns that teach through projects, like planning a golf course to learn geometry angles. More are in the works.

“Frankly, we need another people's movement for education—and we need it for the country,” Riley says.

Advice to young lawyers: “Be a listener. Don't be thinking about just your ideas. Listen to what everybody is saying and respond to it. Be a worker. Be prepared and strong on research.”

Email: [email protected]

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Lack of Independence' or 'Tethered to the Law'? Witnesses Speak on Bondi

4 minute read

Fenwick and Baker & Hostetler Add DC Partners, as Venable and Brownstein Hire Policy Advisers

2 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Greenberg Traurig Litigation Co-Chair Returning After Three Years as US Attorney

- 2DC Circuit Rejects Jan. 6 Defendants’ Claim That Pepper Spray Isn't Dangerous Weapon

- 3Quiet Retirement Meets Resounding Win: Quinn Emanuel Name Partner Kathleen Sullivan's Vimeo Victory

- 4Balancing Hybrid Work With Relationship Building, Newly Merged Ballard Spahr Prioritizes 'Coaching Aspect' of Training New Associates

- 5Texas-Based Ferguson Braswell Expands in California With 6-Lawyer Team From Orange County Law Firm

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250