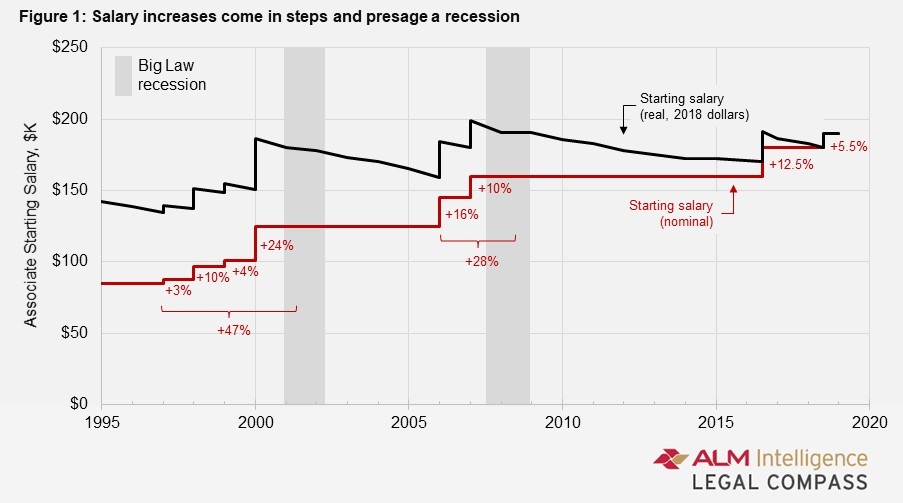

The course we're on is pretty clear. Sometime next year a New York or Bay Area firm will raise associate salaries again. They'll do so in an effort to stem associate attrition. In New York, the attrition will be because associates have been burning out; in the Bay Area, it will be because of competition from the start-up world. That we would have another salary increase so soon after the last is not a surprise—multi-step salary increases seem to be what Big Law does. The scary part? They're a reliable predictor of recession, (see Figure 1).

If the past is a guide then once the salary changes by the early movers have stabilized, Big Law will copy the move unvaryingly nationwide. We should head this off for two reasons. First, another salary increase would be damaging to the profession. It fosters heightened discord with clients and strengthens their resolve to continue taking work away from Big Law. It's not good for firms, partly because they'll fall back on the instinctive response of raising rates, which is counter to their long-term health; partly because it disinclines firms to invest in innovation and technology. It's not even good for associates: it raises the expectations of their billed hours which is not conducive to their long-term participation in the profession; through pressuring profitability, it leans against their prospects for achieving partnership.

The second reason is that a salary increase is an ill-suited response to the problem at hand, namely attrition (particularly at the more senior levels). Increasing bonuses rather than salaries (fixed costs) would be wiser at this point in the economic cycle; a bonus paid out half now and half at mid-year 2019 would directly address the problem we face.

Firm leaders, executive committees and partners broadly should start now to think through these issues. As a guide for such deliberation, the following reviews how the last round of increases unfolded and discusses implications for early mover, and compensation follower, firms.

How the last wave unfolded

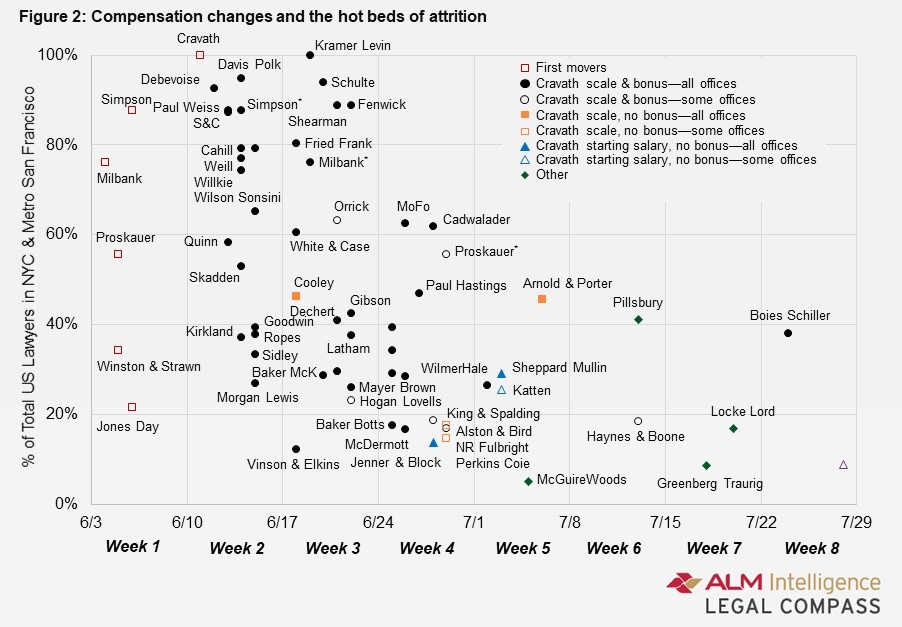

On Monday, June 4, Milbank surprised the world by raising their salary scale to tee off of a starting salary of $190K. Above the Law was ecstatic. Figure 2 profiles what Am Law 100 firms did next: it shows the date of each firm's move, the percent of the firm's lawyers who are in New York City or the San Francisco metropolitan area (the hot beds of attrition pressure), and the nature of the firm's response.

Milbank had not been thought of as a salary leader; the reason for their moving seemed to be “if we don't do it, someone else will”. This isn't a logic; this is a cliché. Presumably they were feeling such intense attrition pressure that it justified the negative attention from clients and the risk (later validated) of being leapfrogged by rivals. On Tuesday, Proskauer followed Milbank. Was the sub-elite tier of New York firms feeling particular pressure? One could imagine that they had become farm teams for higher-prestige firms who could raid their ranks as their needs for lateral talent dictated. But did these firms think that the higher-prestige firms wouldn't respond and thus negate any advantage? Proskauer's move had a smart element that was overlooked at the time: they did not make the increase nationwide, excluding their Newark, New Orleans, and Boca Raton offices. Winston & Strawn also matched on Tuesday; as most of their lawyers are in Chicago, it's not obvious why they moved so quickly. They had no carve out for secondary markets, bringing the increase to Charlotte and Houston. Adjusted for cost-of-living, $190K in New York is equivalent to $300K in Charlotte and Houston.

On Wednesday, Jones Day announced a $190K starting salary as part of their compensation structure. At first look, this makes no sense; they don't play in the same segment as the other early movers. But, on closer reading, it became clear they hadn't really matched the others. They'd done something, opaque to people within and without the firm, that had a $190K number in it somewhere. The move got less coverage in the press than it warranted (a fudged matching would have been a useful model to many other firms) because Simpson Thacher raised the bar that same day: they matched the Milbank salary scale and added an immediately-payable special bonus of $5K to $25K by class year. That they added to compensation via bonus rather than salary struck me as wise: it gets the money to the associates without baking in long-term fixed cost.

There were no more moves that first week, but Week Two started with a bang: on Monday, Cravath matched the Simpson bonus and moved to a salary structure keying off Milbank's $190K starting salary but going to $350K, rather than $340K, for 8th year associates. Over the next three days, a host of big names matched the Cravath move: Debevoise, Quinn Emanuel, Paul Weiss, Sullivan & Cromwell, Kirkland, Davis Polk, Weil, Skadden, Cleary, and Willkie. The moves took on a routine air as they rolled into Friday. But one of the Friday moves stood out: Morgan Lewis matched Cravath. Morgan Lewis is below the top fifty of the Am Law 100 by profit per equity partner; it's largest offices are D.C. and Philadelphia; it doesn't play in the prestigious transaction and litigation practices. Their office footprint took the increase to Princeton, Pittsburgh, Miami, Dallas and Hartford. The prospects for a firewall developing to stop the contagion from elite to next tier firms dimmed.

Week Three brought the predictable, the bizarre, and the inkling of firms breaking from simply copycatting. The predictable included Fried Frank, Kramer Levin, Schulte, Dechert and Shearman & Sterling matching the Cravath numbers, as too did Milbank (the original mover). The bizarre? Vinson & Elkins, the Texas giant, matched Cravath. So too did Baker McKenzie. On the inklings of better thinking being out there: Cooley said they'd forgo paying a mid-year bonus and roll it into year-end; Orrick kept its Seattle, Portland and Sacramento offices off the Cravath scale; Hogan Lovells left Denver and Miami out of its increases. At the end of the week, presumably deciding the landscape was now stable, Latham and Gibson matched Cravath.

Week Four saw Baker Botts and McDermott match Cravath, presumably feeling forced into it by the moves of Vinson & Elkins and Winston & Strawn, respectively. King & Spalding matched Cravath in New York and DC, but kept Atlanta on a separate scale (makes good sense: even $160K in Atlanta is equivalent to $235K in New York). Proskauer trued up to the Cravath level. Friday of that week brought announcements from more firms taking individualized approaches. Alston & Bird matched the Cravath salary structure in NY, DC, LA, SiV and Dallas but kept Atlanta on a different scale; unlike its cross-town rivals at King & Spalding, they eschewed the special bonus firm-wide. Perkins Coie matched the Cravath scale in Chicago, Dallas, LA, San Diego, NY, and DC; for Seattle, Bellevue, and Denver they applied the new salary levels only for 1st and 2nd years billing at a 1,950 hours level; they had no raises in Portland, Madison, or Phoenix. Norton Rose Fulbright did a similar thing: full match (including special bonus) in NY and DC; salary match for 1st and 2nd years only (and no bonus) in Texas and California.

Week Five brought what arguably is one of the thoughtful and rational moves: Pillsbury, ranked 70 by PPP among the Am Law 100, and with offices in the thick of things (largest offices: D.C., New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Palo Alto) awarded no raises, but awarded large bonuses ($25K for 1st years, $100K for 5th years), half payable at mid-year, and half at year end. If the problem you are trying to solve is associate retention in an over-heated market, where other firms are sniping your talent, this is surely the logical response? Haynes and Boone took a pragmatic approach: matched in New York; kept everything else individualized. Another realistic and smart move was by McGuireWoods: no change in salaries (hence, no fixed cost increase) but modest bonuses ($2.5K to $7.5K) to show appreciation.

Week Six saw Greenberg Traurig make a rational move, matching the Cravath scale and bonuses in some offices and practices but by no means in all (raises were communicated individually). This approach embodies a simple reality: the legal world is comprised of multifarious segments, each with distinct supply-and-demand for legal talent. In Week Seven things were dying down, but a notable move was Boies Schiller: it matched the Cravath salary scale but kept to its own bonus formula that lets associates share in revenue. This bonus structure seems smart, especially for more senior associates. It gets away from just hours (which leans against delegation) to something that encourages delegating and starts to bring associates into the business realities of the profession.

For next time: the early movers

As last summer, we can expect that next time there'll be a small number of firms who together shape the new salary and bonus norm for elite firms. To determine what these early movers should do, we start by answering the question: what is the problem they're trying to solve? The market is at a cyclical peak. Associate departures to in-house and other roles have become a problem, particularly for more senior associates. Thus, the problem statement is: how do we reduce attrition, especially of our senior associates, through this frothy market phase?

A first observation is that there are many ways to counter associate attrition that don't involve compensation: the interest level of the work, the training they're getting, respect for their personal lives, willingness of partners to push back on unreasonable client demands, avoiding re-work and unnecessary fire drills, personal bonds with peers and partners, long-term growth prospects at the firm. At some level, it's the refuge of firms who fail on these fronts to rely most heavily on compensation as a retention tool. This is risky: compensation begets complaisance; it does not beget loyalty.

To the extent that compensation is part of the response, and given the 'market froth' nature of the problem, it would seem much smarter to increase bonuses than salaries. Even allowing for inflation, salaries today are essentially as high as they've been anytime in the last twenty-five years, (Figure 1 again); thus, there is no historical logic to put compensation increases into salary rather than bonus. Salaries add to fixed costs in perpetuity, the exact opposite of what a wise firm would do at this point in the economic cycle as it constrains a firm's ability to maintain investments through the downturn.

With respect to bonuses, it seems inconsistent to me to use bonuses as a retention mechanism and then to pay bonuses without any retention element to them. I understand the 'thank you' element of announcing a bonus today and paying it out tomorrow; I understand the return on investment of awarding a bonus today and paying it out half now, half in six months. Thus, a concrete suggestion: increase 2018 year-end bonus awards significantly (double, or more); pay out half in December and half on 1 July, 2019 to those still with the firm. Also, because the retention challenge is most acute at the more senior levels, skew the bonus amounts much more to the senior levels.

To the extent that firms are incorrigibly inclined to increase salaries, then I'd suggest a couple of changes. First, don't increase starting salaries; instead increase only those at the higher seniorities. The starting salary of $190K is more than enough to attract top talent coming out of school; paying $305K to a sixth-year has exposure to their being picked off.

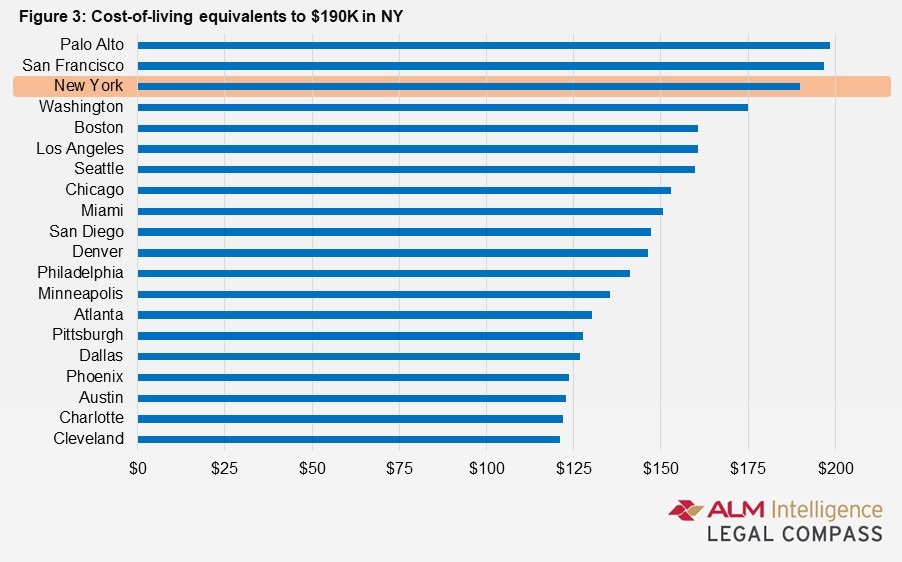

Secondly, salary increases shouldn't be the same across all offices. But what, you say, of having “one firm” as a firm value? It's naïve to think of values as absolutes; values inherently conflict. Another value firms would espouse is to treat people fairly. Is it fair to associates in New York that their brethren in Chicago are paid an amount that gives them 20 percent more purchasing power? From an economic perspective, the amount to pay Big Law lawyers in Chicago should key off the compensation they would get at an in-house or 'small law' position in Chicago—their true alternatives—not off the compensation of a Big Law lawyer in New York. As Emerson observed: a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.

For next time: the compensation followers

The compensation followers face a similar challenge to the early movers (hugely frothy market; high attrition, especially at senior levels) with additional twists: many have to contend with attrition not just to in-house positions but also to higher-prestige firms; and their client base is more sensitive to pricing and the optics of associate compensation; they have a social contract with associates that includes their billing fewer hours than their New York brethren and more exposure to partners; their business models leave less profit cushion for, and hence less flexibility for maintaining investments in, the downturn ahead. Thus, their problem statement: how do we respond to the first movers in a way that avoids increased defections and maintains associate morale, but doesn't strain client relationships, inadvertently put more undue pressure on associates, or limit the firm's capacity to maintain investments in the forthcoming downturn.

In considering this, it's important to appreciate an uncomfortable truth: a small group of super elite firms—a subset of the old-line Wall Street firms; the newcomers of Kirkland, Gibson, and Latham; and the elite litigation boutiques of Quinn Emanuel and Boies Schiller—are simply on a profitability trajectory different from the rest. It is madness for other firms to key the largest single element of their cost structure off of the pay scales of this super elite. There must be an uncoupling and the sooner, the better. But it's more than a difference in firm profitability; it's also a difference in the social contract between firms and their associates. For this super elite, associates are trading their waking hours, long-shot odds at partner, and limited exposure to training from partners for high prestige and compensation. It's a different pact at other firms: yes, there are long hours, but the prospects for partnership are greater in lower leverage environments, as is the opportunity for learning directly from partners; there is more respect for the whole person; relationships are formed that are akin to family and last a lifetime. Matching the super elite on compensation need not be part of the package.

Another guideline for the compensation followers is not to feel rushed. One of the positives from the last round of increases, even if not lauded by Above the Law, is that firm responses played out over eight weeks. A message to associates that says the firm is watching the market, and that any move will be back dated, should quell any anxieties.

A further principle: firms should ground their response in a realistic assessment of where they stand in the market. In conversations with partners about the befuddling firm moves last time a word that came up frequently was 'hubris'. The idea is that some firms were willing to pay their associates at a Cravath scale so that they can preserve the illusion that they play in the super elite segment. A variant of this is that firm leaders want to do so as it feeds their grandiosity, and that they justify it to themselves it by saying it's important to their partners. This is bizarre. Lawyers are by nature more skeptical than 90 percent of the population. Big Law partners are not self-delusional fools. There may be instances where partners need to encourage their leaders, if not to be humble, then at least to be realistic.

Firms should also view their responses as an opportunity to move toward more rational comp structures. One dimension of this is geography: what cities need to follow New York? Practices vary by geography. Even Washington D.C., despite its physical proximity to NY, tends to have a different practice mix (more regulatory, more government-focused) with lower leverage, more hands-on training by partners, and greater chances for associates to make partner. This is a different associate-firm pact than that prevailing in New York practices; New York compensation need not be a part of the DC social contract. Cost-of-living comparisons reinforce the distinction: $190K in New York is equivalent to $175K in D.C. Figure 3 shows the salary equivalent of $190K in New York across the twenty cities with the greatest number of Big Law lawyers. Beyond the Bay Area, and arguably Washington and Boston, one is pretty hard-pressed not to see paying lawyers the same as in New York as inequitable to people in New York.

A single salary structure nationwide is a vestige of when coastal city firms didn't have national footprints. As these firms grew and their new offices were small, a single salary scale was of no great significance. But now that these offices have matured, a single structure is a non-trivial inequity and a drag on firms' ability to invest. Unwinding the current system is best done slowly and, in particular, by forgoing increases over time.

Another aspect of a moving toward greater rationality centers on the tradition of lock step salaries and hours-based bonuses. These systems are embodiments of Taylorism management theories of the 1890s; they don't belong in people-centered businesses of the 21st century. People don't progress at a single rate; a single measure of performance belies the multifaceted nature of the role; using hours as this single measure discourages efficiency and delegation. It's daft: all law firms salute the notion that their people are their most important resource; they then manage their compensation with the techniques of the steam locomotive era. To state the obvious: progression rates should vary by individual; performance assessment should be multi-faceted and vary with the seniority of the role; and individuals should be guided on development through personalized interaction not arithmetic.

I was confused by the response of some firms last summer to move to the $190K starting salary but not to raise salaries higher up the scale. This must have offended the senior associates they most wanted to retain. And I doubt it convinced offerees: if they were unaware they were signing on to a lower salary ramp they probably shouldn't have been hired. I was also befuddled by the firms who matched the new $190K salary scale but did not award a bonus; this looks like the antithesis of what one should do where the challenge is stemming attrition ahead of a recession. Other firms went to the higher salary scale but attached a billable-hours requirement. I understand the logic of this: it tells associates that if they work like their brethren at New York practices, they'll get compensated like them. But the approach has some downsides. It sends an implicit message that associates aren't billing enough hours. Is that the message firms meant to send? I understand sending that message if the issue is that associates aren't working hard enough. But at many firms, working New York M&A hours is not part of the social contract with associates. Their partners don't do it and don't particularly want their associates to do so—it's not what their firm is about. It also mixes apples and oranges: I've seen lots of businesses over the decades; almost all reward employees with a base and bonus; none have a variable base; variable compensation is called bonus. More generally, this approach misses an opportunity for openness: associates know they enjoy a different compact with their employer firms as part of which they don't work like New York associates. There are loyalty returns to honesty.

A closing thought

Now is the time for leaders to talk with their executive committees and partners about how to handle the next round of compensation changes. The increases won't be fun. But there's a silver lining: it's an opportunity for the increasingly-variegated industry to break from its vestigial 'single scale' nationwide system, and for firms to bring their internal compensation and development processes out of the 19th century. Let's not blow it.

Hugh A. Simons, Ph.D., is formerly a senior partner and executive committee member at The Boston Consulting Group and chief operating officer at Ropes & Gray. He writes about law firms as part of the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program. He welcomes readers' reactions at [email protected]

More information on the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program can be found here.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Will a Market Dominated by Small- to Mid-Cap Deals Give Rise to a Dark Horse US Firm in China?

'Ridiculously Busy': Several Law Firms Position Themselves as Go-To Experts on Trump’s Executive Orders

5 minute read

The Law Firm Disrupted: For Office Policies, Big Law Has Its Ear to the Market, Not to Trump

Trending Stories

- 1We the People?

- 2New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 3No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 4Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 5Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250