At 25, Bartlit Beck Is Still on Trial. Is Its Model Winning?

An 80-lawyer trial boutique may have lessons to teach Big Law about developing talent.

December 06, 2018 at 03:54 PM

9 minute read

Bartlit Beck's renovated offices in Chicago. (Credit: Garrett Rowland | Design by Gensler)

Bartlit Beck's renovated offices in Chicago. (Credit: Garrett Rowland | Design by Gensler)

- For a quarter-century, national litigation boutique Bartlit Beck has made its name in a declining business: trials.

- The firm's talent model may provide insights for a lower-leveraged Big Law market.

This fall Bartlit Beck moved into renovated office space in Chicago, complete with all the modern touches: Windows where walls used to be, maximalist video screens and a minimalist mock court that the firm says is what digital-first courtrooms of the future will look like.

The renovation coincided with the anniversary of Bartlit Beck's founding 25 years ago, when a group of trial lawyers broke away firm from Kirkland & Ellis—which, not for nothing, now houses more than 600 attorneys just down the street. For all the office's new-fangled features, the space still honors the history of the building that houses it: Chicago's original criminal courthouse, constructed in 1893. Conference rooms are named after high-profile trials that occurred here, such as the infamous Black Sox scandal following the rigged 1919 World Series.

The modern space in an old building is fitting for a young law firm that is, in many ways, a throwback to an earlier time. Bartlit Beck has become one of the country's best-known brands for courtroom advocacy thanks to a model that cherishes one-on-one mentorship, demands teamwork and envisions a partnership track for every lawyer at the firm.

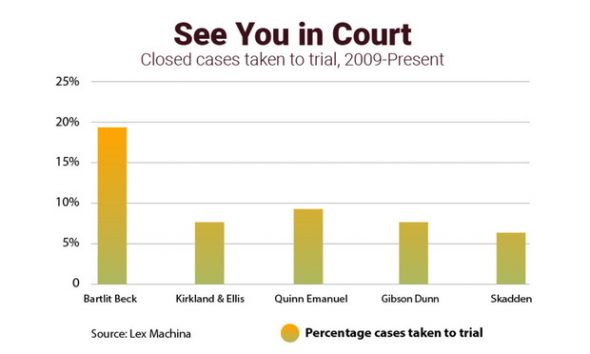

And in an age of ever-declining trials, Bartlit Beck still goes to the finish line on a higher percentage of cases than almost any law firm in the country. From 2009 through late 2018, the firm went to trial in nearly 20 percent of its completed cases in five major types of litigation, according to data from Lex Machina. That compares to a range of 7 to 9 percent for four of the nation's best-known Big Law trial firms: Kirkland & Ellis, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher and Skadden, Arps, Slate Meagher & Flom.  There are a number of reasons why Bartlit Beck goes to trial so often. The simplest one is that they win. Jason Peltz, the second managing partner in the firm's history, who gained the title earlier this year, said the firm has historically won about 85 percent of its cases that go to verdict.

There are a number of reasons why Bartlit Beck goes to trial so often. The simplest one is that they win. Jason Peltz, the second managing partner in the firm's history, who gained the title earlier this year, said the firm has historically won about 85 percent of its cases that go to verdict.

The firm has to know its track record, since a portion of its fees in virtually every case is paid only if the firm is successful. As Bartlit Beck looks toward its next 25 years, leaders say they have no plan to change that model, and they are most focused on attracting the next generation of top trial lawyers. Its hiring is vastly different from the standard Big Law approach. Roughly 80 percent of the firm's lawyers are partners (67 partners, 15 associates and 2 special counsel are listed on its website), and it adds only one to two new associates a year.

Many expect large law firms will struggle to maintain their traditionally high leverage models as technology makes the practice of law more efficient—and as clients become increasingly reluctant to pay high billable rates to train inexperienced lawyers. In that scenario, bigger firms could look to incorporate aspects of Bartlit Beck's talent and training model.

They could start with a simple question: When a firm expects every lawyer to become a partner, what does it mean to be an associate?

Business Is Good

Fred Bartlit left Kirkland & Ellis in 1993, after 33 years at the firm, taking 18 lawyers with him, including fellow name partner Phil Beck. Bartlit and Beck left following a dispute over the merits of alternative and success-based fees. With a belief that the billable hour only fueled inefficiency, Bartlit in a 1995 American Lawyer article evangelized the rise of success-based payments and predicted a proliferation of firms like his. That revolution remains to be seen. The New York Times is still running op-eds decrying “The Tyranny of the Billable Hour.”

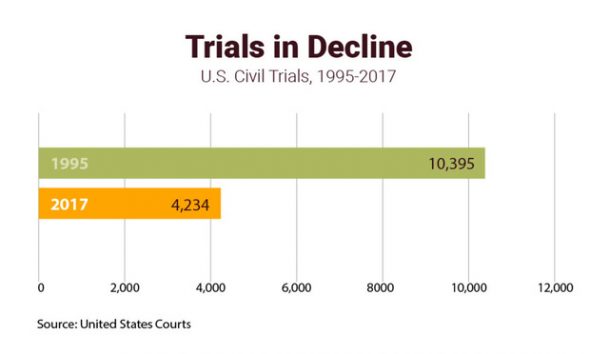

However he planned to get paid, Bartlit didn't necessarily pick the ideal climate to grow a trial firm. The number of civil trials in U.S. federal courts has been more than cut in half since the firm has been in business. In 2017, there were 4,234 such trials, compared to 10,395 in 1995.

Still, the firm has made a good business out of going to court, even if it declines to discuss compensation or profitability figures. Its reputation remains burnished by the work Bartlit and Beck did to help George W. Bush win a contested Florida election in 2000, with Time Magazine calling Beck “Bush's new star” for his work cross-examining a Democratic voting machine expert. In more recent years, it has worked on behalf of major clients including Citadel, DuPont, United Technologies, Nicor Inc. and Bissell Corp.

Still, the firm has made a good business out of going to court, even if it declines to discuss compensation or profitability figures. Its reputation remains burnished by the work Bartlit and Beck did to help George W. Bush win a contested Florida election in 2000, with Time Magazine calling Beck “Bush's new star” for his work cross-examining a Democratic voting machine expert. In more recent years, it has worked on behalf of major clients including Citadel, DuPont, United Technologies, Nicor Inc. and Bissell Corp.

Jason Peltz

Jason PeltzBartlit Beck this year was selected among a group of nine top litigation firms by BTI Consulting Inc., joining a list that included Gibson Dunn, Kirkland & Ellis, Quinn Emanuel and Skadden (the top four) and Jones Day, Sidley Austin, Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz and Winston & Strawn.

Peltz, the managing partner, says clients often select Bartlit Beck to send a message to their opponent in litigation. That reputation is also part of why the firm goes to trial more frequently than other firms, but Peltz said it also can lead to better settlements.

“It absolutely sends a signal to the other side that this case will be ready for trial,” Peltz said. “We want to send that signal. Because sometimes when the case is most ready for trial, that's when you can get the best settlement.”

No Secret Sauce

According to Peltz, the firm works on every matter from the start as if it will be proceeding all the way to trial. That's why lawyers with first-hand trial experience are so valuable, and why Bartlit Beck does all it can to fast-track its young lawyers' development. Associates can't prepare a case as if it's going to trial if they don't know what a trial entails.

Bartlit Beck also staffs cases differently than other firms. It works in smaller teams composed of more experienced lawyers compared to most large firms. The average lawyer at the firm has been practicing for 16 years. It also doesn't typically hire lateral partners.

Rebecca Weinstein Bacon

Rebecca Weinstein Bacon“People ask me all the time, 'What's your specialty?'” Peltz said. “Our specialty is making complicated matters simple. Our specialty is presenting a client's case in a very credible, simple, real way to juries across the country. And in doing so, being the teacher to juries along with the judge and ourselves—because we're all learning all the time.”

Lawyer development remains a core component of the firm's model. Thirty percent of Bartlit Beck lawyers have first-chair trial experience, the firm says. Last year, 64 percent of its lawyers appeared in court on a substantive issue; 72 percent took defended a deposition; and 57 percent held a substantive role on a trial team.

“Every member of the firm that we work with, from the newest associate to Phil Beck, works closely with our in-house team on all aspects of our cases and makes valuable contributions,” said Shawn Fagan, chief legal officer at Citadel. “They are collaborative, creative, and deliver results for Citadel.”

Recruiting for Emotional Intelligence

Nico Martinez is an example of the kind of candidate the firm attracts. A 2013 Stanford Law graduate and a 2005 College Jeopardy champion, Martinez joined in 2016 following three years as a clerk, first for a federal appeals judge, then a U.S. district court judge and finally a California Supreme Court justice.

Nico Martinez

Nico Martinez“I knew Bartlit Beck was extremely selective in its hiring, and so I think just to get an interview in some ways felt like an achievement,” Martinez said.

Martinez said on his first day at the firm, he showed up in the Chicago office, signed some employment-related forms and flew with a trial team to meet a client in New York City. They were preparing for a trial scheduled in just a few months.

The firm's associate pool also benefits from the firm's rejection of the billable hour and its belief that every lawyer it hires has the potential to make partner. Martinez said that means associates don't view each other as competition and they often help each other. For instance, when Wesley Morrissette, a 2014 graduate of Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law, was tabbed to give an oral argument in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit this year, a group of about five associates helped him prepare, Martinez said.

“If somebody gets to stand up in court in a high-profile case and cross-examine a witness a couple weeks after joining the firm, that's a huge benefit to the firm overall and to me, because I know these are people I'm going to be able to work with for many years,” Martinez said.

As for what Bartlit Beck looks for in its associates, Rebecca Weinstein Bacon, a partner, said it's about emotional intelligence as well as brains and credentials. Much of the interview process is a sort of personality test designed to answer one question: Does the person seem presentable in front of judges and juries?

“We're looking for high EQ,” Bacon said. “And I think we can tell when somebody has high EQ and when they don't.”

Either way, it won't be long before Bartlit Beck takes another case to trial, and another jury weighs in.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Legal Tech's Predictions for the Business of Law in 2025

Thwarting of $14B US Steel Deal Won't Dampen Japan-U.S. M&A, Lawyers Say

New Year, New Am Law 100: Challenges Await These Newly Merged Law Firms

7 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Discovery Seeks to Link Yale University to Doctor in Fertility Scandal

- 2On The Move: Energy Infrastructure Pro Joins Moore & Van Allen, Adams & Reese Changes Atlanta Leadership

- 3Miami Attorneys Secure $4M Settlement Despite Insurance Limits

- 4NY Judge Admonished Over Contributions to Progressive Political Causes

- 5Legaltech Rundown: Alexi Launches an AI Litigation Tool, Hotshot Announces Private Equity Practice Courses, and More

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250