How Good Are Lawyers in Mid-Market Cities?

Lawyers in larger cities don't necessarily keep clients more satisfied, according to the fifth major finding out of AdvanceLaw's GC Thought Leaders Experiment.

December 18, 2018 at 05:19 PM

7 minute read

A view of the Portland, Oregon, skyline.

A view of the Portland, Oregon, skyline.

Wall Street, K Street, Bay Street, Silicon Valley—the locations are legendary and instantly recognizable. They are places of incredible financial and political influence, in or near some of the world's largest cities. And each attracts high concentrations of corporate lawyers and large law firms. So it's no surprise that many of the largest companies send most of their work to lawyers in these cities.

But is it the right call? Put another way, and this is the question we're posing, should clients more actively consider significant but less expensive cities like Denver, Phoenix, St. Louis, Minneapolis, Portland, Baltimore, Detroit, Cleveland, Tampa, Milwaukee, Charlotte and Atlanta for their major legal work?

(Granted, we are actually talking about “mid-to-large market” cities, where GCs are likely to find strong depth in legal talent—not “mid-market” cities—but that would have made for a pretty awkward title.)

That's the question more general counsel are asking, and the answer they arrive at could reshape the legal market. Soon after signing the Open Letter announcing the Thought Leader Experiment, Lee Reichert, chief legal officer of Molson Coors, remarked: “I'm interested to see how the performance of firms in the biggest cities compares to that of firms elsewhere—on things like quality, responsiveness, outcomes and expertise. Are there differences? Given the breadth of our business, this finding can influence how we make counsel selection decisions.” And in an age when technology allows clients to work seamlessly with lawyers around the country, clients have more of a choice than ever.

Following last month's highly controversial data finding that the largest, most pedigreed firms are lagging, we wanted to look at the effect of location. How do lawyers in the largest cities perform relative to their peers in smaller but still major cities? The result overall is a statistical tie in terms of service quality—we saw no material difference in performance—but lawyers in the less-populated cities performed markedly better on cost and efficiency.

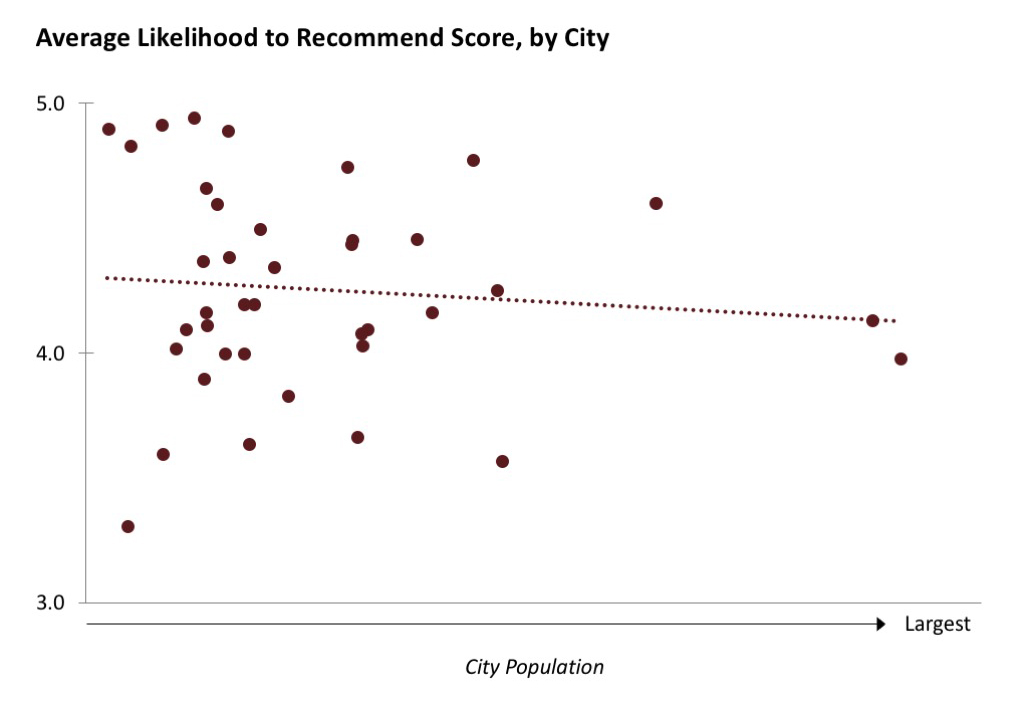

By way of example, if we look at the 40 major metropolitan areas with the largest number of legal matters in our dataset (specifically, 36 U.S. cities and four international cities), and line them up in the chart below by size of city (largest on the right) and likelihood to recommend (out of 5; highest scores at the top), we get this result:

Each dot is a different city, and what the chart shows is that there is no meaningful relationship between the size of the city where the lead lawyer is located and the client's likelihood to recommend that lawyer (our benchmark metric of client satisfaction).

We have also run this analysis for each of our other performance metrics—things like quality of work, responsiveness, legal expertise, solutions focus, and outcome—and across 1,400 matters, spanning over 100 cities in 19 countries, the pattern remains about the same. And we controlled for different variables, including law firm size.

For all the talk about prestige locations and how mega cities attract all the best talent, there is no real performance difference. In fact, as the slight downward slope of the best-fit line shows, the largest cities in the data set have marginally lower performance scores than other locations, though this is not statistically significant. (And again, the result is largely the same across various client-service metrics.)

However, as noted above, the lawyers in the largest of cities are more expensive. This comes as no surprise, but we verified this by looking at the data in two ways. First, by looking at reported partner rates on our 1,400 legal matters, and second, by examining in-house counsel assessments of the cost and efficiency of the legal work being done. Put simply, if clients gravitate to the very biggest of cities, they'll pay more; and, on average, they don't receive better service quality.

We think part of the reason that there isn't a quality improvement when turning to lawyers in the largest cities is that quality and depth of talent in other markets has been growing steadily over the years. That said, it is likely that the in-house counsel in our data set are currently tapping into the very best and brightest in significant (but non-mega) cities.

And therein lie a couple of limitations to our observation. First, there are some categories of highly specialized legal expertise that tend to be found predominantly in certain major cities—think banking and securities work in New York or government work in Washington, D.C. Second—and this is an important limitation, too—only so much work can flow into some of these “secondary” cities before elite talent will be in short supply.

That said, we can say that at least under current conditions, the in-house teams venturing outside mega (or money-center) city firms are receiving very strong legal service at substantially lower cost. (We looked, by the way, at the nature of the work being sent to these “mid-to-large market” cities, and it includes significant high-stakes work.)

Despite this, clients tend not to avail themselves of this opportunity. Perhaps they rely on the premise that the biggest cities attract all the elite talent (or at least that it's difficult to find the elite talent in other cities), so it is worth paying premium prices. But consistent with the data above, our discussions with general counsel suggest that top talent is increasingly dispersed, with a growing number of elite lawyers and sizable firms located in cities across the country.

This reminds us of what Bill Deckelman, GC of DXC Technology and another participant in the experiment, said about hiring supposedly elite firms: “The root of the problem is that we clients go to the well with certain firms because we're making buying decisions based on the firm's reputation for service quality 15 or 20 years ago.”

Note that we are not saying there isn't an incredible amount of elite legal talent in the largest cities that should be tapped—there is. Likewise, we are not saying that clients can or should send all their work to the so-called “mid-to-large” cities—there are obvious limits to this. But we are saying GCs and their teams should resist defaulting to the usual locations out of habit or history. The data suggests there is a major opportunity here, under current market conditions, to get great talent at lower cost, working extra efficiently.

It's why AdvanceLaw clients seek our help identifying high-performing lawyers and firms without a bias to location. They understand there is great talent out there, but they have no other system to verify their quality.

Related, if clients don't seize this market opportunity, we will, to paraphrase Deckelman, send the wrong signals to law firms and reward the wrong behaviors. Specifically, lawyers will face increasing pressure to be in only a few key cities despite the obvious cost advantages that inure to both firms and clients when lawyers work in less expensive places.

Our message to clients is to embrace this labor arbitrage opportunity, and not always run to the bright lights of the biggest cities. Find some mid-to-large markets that are attracting great lawyers looking for a different quality of life or returning to their hometowns. And to law firm lawyers who have chosen to practice in a significant but not money-center city: enjoy your relatively quiet expanse, shorter commute, and lower cost of living. Armed with information like this data finding, the clients are coming.

Michael Williams is CEO of AdvanceLaw and Aaron Kotok is managing director.

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Three Akin Sports Lawyers Jump to Employment Firm Littler Mendelson

Brownstein Adds Former Interior Secretary, Offering 'Strategic Counsel' During New Trump Term

2 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1How ‘Bilateral Tapping’ Can Help with Stress and Anxiety

- 2How Law Firms Can Make Business Services a Performance Champion

- 3'Digital Mindset': Hogan Lovells' New Global Managing Partner for Digitalization

- 4Silk Road Founder Ross Ulbricht Has New York Sentence Pardoned by Trump

- 5Settlement Allows Spouses of U.S. Citizens to Reopen Removal Proceedings

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250