The Next Recession Could Cost 10,000 Lawyers Their Jobs

Thousands of layoffs are looming when the impending recession hits. Whose jobs are most at risk?

February 26, 2019 at 05:00 AM

10 minute read

As a looming recession approaches, a look at history, plus some judgment, can tell us a lot about how organizations will manage their lawyer numbers once it arrives. It's a clear, disturbing and instructive tale.

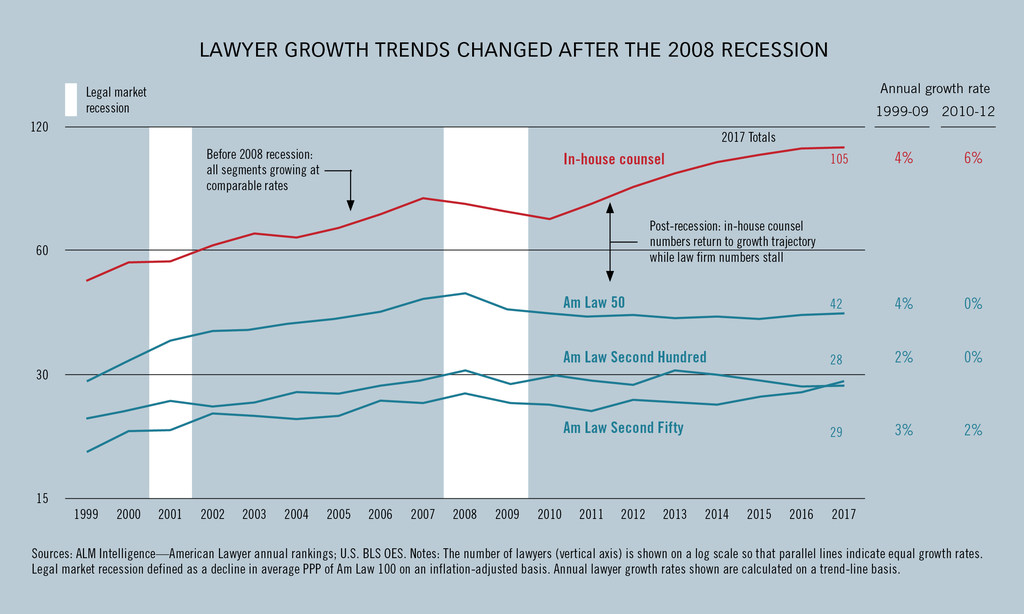

Let's start with some history. In studying the trends in U.S. lawyer head count over the last 20 years, both in-house and at major law firms, one thing jumps out: the stark difference before and after the 2008 recession. Before 2008, all segments were growing; after 2008, in-house lawyer growth accelerated while growth in law firms ground to a halt.

Why the change? A different purchasing environment has held sway at client organizations since the recession. There's been a rejection of ever-increasing hourly rates for the commodity offerings from much of Big Law. We've witnessed the rise of the ambidextrous general counsel, taking work away from overpriced firms with one hand while using the other to execute it in-house or move it to lower-cost firms and nontraditional providers.

Changes over the last two years are especially informative as we think about the effects of the coming recession. From 2016 through 2017 (the latest data available), in-house counsel stopped growing. From 2015 through 2017, the Am Law 50 finally grew a little, and the next 50 firms registered their strongest growth since the recession's onset. I don't believe this marks the end of the ambidextrous shifting of work away from law firms. Rather, general counsel stopped growing in the belief that we're nearing a cyclical peak: Instead of hiring more in-house lawyers than they need outside of peak times, they are sending more work to outside counsel, effectively using their law firms as surge capacity. When the peak passes, this work will be taken back in-house, leaving law firms with a capacity overhang.

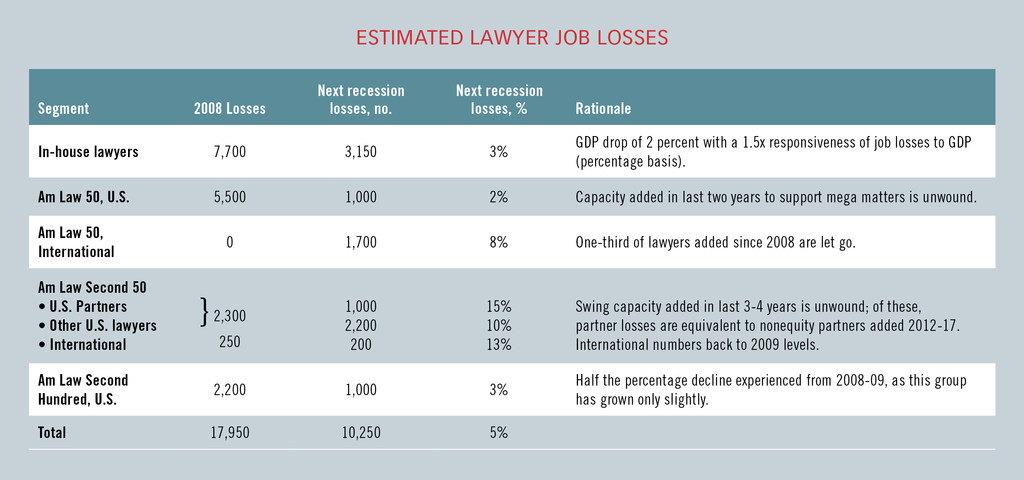

The Am Law 50 appear particularly affected by the emergence of the post-2008 purchasing environment—their lawyer numbers shrank, and they are still 4,300 lawyers, or 9 percent, below their 2008 level. The elite firms within this group have become too expensive to offer clients a one-stop shop in the form of a broad, institutional relationship. Instead, clients have kept the elite firms for work for which there are few viable alternatives, but have looked to lower-priced firms to handle work they can do competently. This has wrought an important change beyond the reduction in demand: The work mix at elite firms is more concentrated on mega matters—major transactions and big-ticket litigations that can generate a fee of $50 million or more. When the economy is strong and such matters abound, elite firms perform stunningly well. But when the economy turns, big deals dry up and firms are less inclined to pursue major litigation. The coming recession will be the first time we see how the elites' new business mix—driven by major matters rather than relationships—fares in a downturn.

Another salient dynamic within the Am Law 50 is that they shrank at home and grew aggressively abroad. Over the past 10 years, 31 of the Am Law 50 have contracted their number of U.S. lawyers; 38 have grown internationally. Because international practices are less profitable than their U.S. counterparts, and because most law firms have anachronistic compensation systems that don't take adequate account of the variability of practices' profitability, there is hefty subsidization of international partner compensation by their U.S. brethren. Such subsidies are easily overlooked when international partner numbers are small and profits are strong; in the coming recession, they'll demand attention.

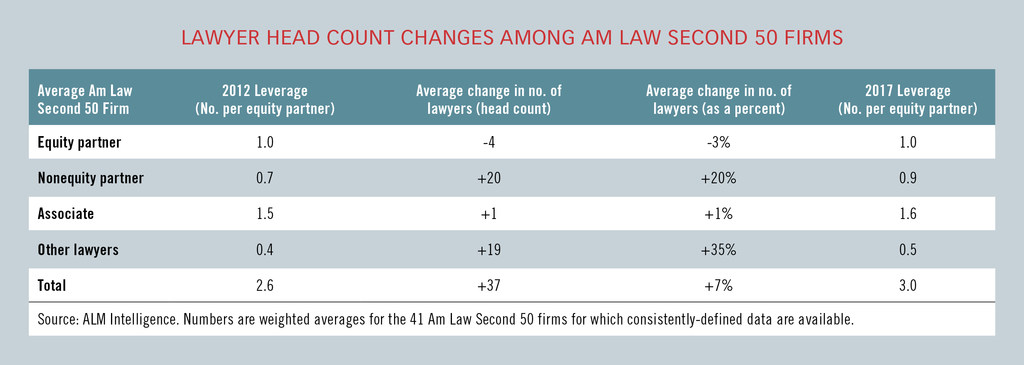

Likewise, there have been changes within the Am Law Second 50 that foreshadow what will happen when the economy turns. Over the past five years the average Second 50 firm increased its equity partner leverage from 2.6 to 3.0. It's noteworthy that the increase came primarily through increasing the number of nonequity partners and “other lawyers,” which captures both staff attorneys and counsel—senior attorneys who are close to partners in capability. Between the nonequity partners and counsel, this represents a stunning increase in the lawyer cohort just below equity partner. This oft-overlooked group can be a holding pen for lawyers who aren't going to be made partner but who are important, and profitable, when business is strong. When business softens, their position is more circumspect.

In-House Implications

At the depth of the 2008 recession, U.S. GDP fell 4 percent below its prior peak. I don't believe we'll see this level of contraction next time—the 2008 recession was the deepest and longest-lasting contraction since World War II. With GDP down 4 percent, the number of in-house lawyers fell by 10 percent—a ratio of 2.5 points for ever point of GDP decline. I expect the response next time will be more muted, as there have been fundamental changes in in-house law departments.

The case for in-house counsel displacing outside lawyers has been proven—and clients' chief financial officers now understand it. Law departments have paused their hiring in the last two to three years, recognizing that they're near a cyclical peak. This is in stark contrast to last time, when they grew strongly from 2004 to 2007. General counsel have grown into more experienced business executives. It takes time for a GC, coming from a law firm, to figure out they have to actively manage their internal resources—there's no recruiting department supplying people each year—and to do so with some deft corporate politicking. And GCs are more respected as managers of their departments, and thus can assert more control.

If the economy were to contract 2 percent and there were a 1.5:1 ratio between lawyer jobs and GDP (compared with 2.5:1 last time), we'd see a 3 percent drop in in-house lawyer numbers (compared with 10 percent last time).

All that said, GCs should start making their case now to CFOs and management committees for keeping their compensation budgets whole when the recession hits. This isn't to say GCs should be focused exclusively on stabilizing their existing personnel. The new breed of ambidextrous in-house counsel needs to be as sharp a lawyer as a law firm partner—and a better business partner. It's a tall order. The recession will present opportunities for upgrading staff. It provides cover to let people go, and there will be many talented lawyers leaving law firms. A recession is a terrible thing to waste.

Effects on Elite Firms

When business cycles turn, huge transactions and massive litigations dry up. The elite firms that have become reliant on mega matters will experience a disproportionately strong drop in demand. Some may get lucky with major litigations (arising from big transactions) that extend beyond the recession's immediate onset, but all will eventually see a serious profit contraction. To some degree this is just the inherent downside in their otherwise stunningly attractive mega matter business mix. But it should also serve as impetus for elite firms to figure out if and how they can maintain broad, institutional, “go-to” firm status with certain key clients.

The profit crunch will propel many of these firms to take a hard look at their outsize international growth. A starting point is to build an accurate assessment of partner practice profitability. Then they must make sure their compensation systems are rewarding partners consistently with these profitability profiles. The London elite learned the hard way that growing in less-profitable markets without having wide variations in compensation from the global average exposes profitable partners to being picked off by rivals. Beyond this, there are questions of practice portfolio strategy—adding international practices does little to strengthen domestic positions. Firms should be particularly circumspect of international practices without high leverage, and London will warrant a particular focus given Brexit uncertainties.

However, these firms shouldn't overlook changes too to their domestic businesses. The elite law firms are becoming more like elite consulting firms. But there remain major distinctions in how partners are developed. The elite consulting firm partnerships are two-tier, with progression through the lower tier being explicitly “up-or-out” and with the upper tier being explicitly “perform-or-out” indefinitely. Upper-tier partners are reviewed formally every three years with explicit discussion not just of commercial contributions, client relationships and institution building, but also of developing other partners and helping them succeed. I don't recommend law firms simply move to the consulting model, but I do believe that many law firms would benefit enormously from having more explicit discussions with partners about how their careers should evolve, as well as outplacing those who don't develop accordingly. The coming recession will make acute the need for such discussions.

The Broader Am Law 100

Since 2014, the growth of in-house lawyer numbers slowed while that of Am Law 100 firms, particularly the Second 50, grew as general counsel used outside counsel as the swing capacity to get them through the peak. When the cycle turns, this outsourced work will be taken back in-house, and firms will be left with a lawyer capacity overhang. As firms review their newly under-utilized lawyers, they will look to cut the seemingly bloated ranks of nonequity partners and counsel. But doing so without dexterity would be a grave error. This group can be thought of as comprising three distinct types of senior lawyer:

- Those with an important, but not high-risk, niche specialty that is not one senior associates must master on the way to partner, such as blue-sky law;

- Broadly accomplished lawyers who lack the requisite relationship-building and commercial skills to be an effective equity partner in a modern law firm; and

- Those with the full skill set to be effective equity partners but who have not been elevated due to a disinclination to expand the equity ranks.

Most firms will retain their specialists in the first category, and, after some protectionist bickering, transition out the incumbents in the second. The challenge, bizarrely, is with the third group. A disinclination to expand the equity ranks is a wise proclivity; the unwise corollary is to pass on electing a high-potential lawyer to the equity ranks in order to maintain in those ranks a lawyer who has failed on a sustained basis to perform as can be expected of a full equity partner in a modern law firm. The easy option is to transition out the nonequity partner; the harder option, but the one critical to a firm's long-term vibrancy, is to transition out the equity partner and promote the nonequity one.

A back-of-the-envelope estimate of lawyer job losses in the forthcoming recession shows total losses, at 10,000 lawyers, will be significantly below the nearly 18,000 jobs lost last time. Notably, the changes at law firms, while recession-related, are not truly cyclical swings. Rather, they are structural changes whose necessity becomes clear in the down part of the cycle. The corollary, of course, is that one doesn't have to wait for the cycle to turn to make changes. Indeed, wise firm leaders are working on them already.

Hugh A. Simons, Ph.D., is formerly a senior partner and executive committee member at The Boston Consulting Group and chief operating officer at Ropes & Gray. He writes about law firms as part of the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program. Contact him at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Alston & Bird Adds M&A, Private Equity Team From McDermott in New York

4 minute read

Veteran Federal Trade Law Enforcer Joins King & Spalding in Washington

4 minute read

Houston Trial Lawyer Mary-Olga Lovett Leaves King & Spalding to Open Boutique

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250