Big Law's International Tilt Has Gone Too Far. A Restructuring Beckons.

Head count is shrinking in major domestic markets and growing in major international markets, dragging down law firms' profitability in the process.

April 23, 2019 at 09:48 AM

12 minute read

Credit: Roberto Jimenez.

Credit: Roberto Jimenez.

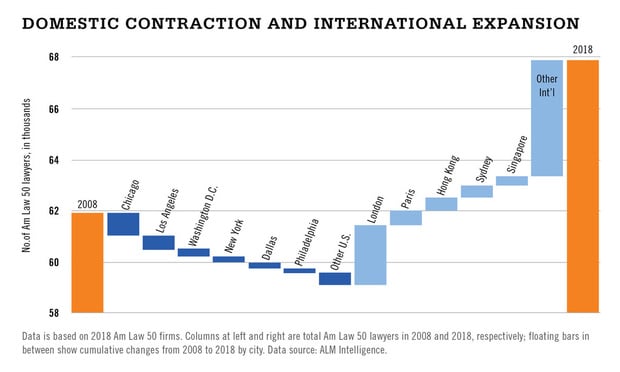

While the Am Law 100 ranking tells us about the comparative financial strength of individual firms, a look inside the firms—specifically at the number of lawyers by office—reveals an important dynamic affecting the financial outlook of the industry: Since the last market peak, in 2008, the 50 largest U.S. firms contracted by 3,000 lawyers in the United States while growing by 8,700 lawyers abroad. As a result, international lawyers now comprise 35 percent of total Am Law 50 lawyers, up from 24 percent a decade ago.

This tilt toward overseas markets puts a drag on firm-average profitability. The drag caused by the lower price point and billed hours of international markets is well known, but it has been compounded over the past decade by so many of the Am Law 50 growing internationally at once, thereby increasing competitive intensity and dramatically shifting market power to clients. The lower profitability of international markets is an issue for partnerships with firmwide lockstep compensation because it leads to U.S. partners effectively subsidizing the compensation of their overseas brethren. As firms shift lawyers to international markets, these subsidies have grown. The growth can be overlooked in the froth of today's market, but it will cause severe tension when the economy turns. This is more than a matter of fairness among partners; it's a matter of strategy. Substantial, sustained subsidies augment the risk of the highest-value U.S. partners being lured away by domestic rivals. Wise firm leaders are getting out in front of these issues now.

Leverage the Am Law 100 data with firm comparison and key performance data, exclusively on Legal Compass. Access Premium Content

Leverage the Am Law 100 data with firm comparison and key performance data, exclusively on Legal Compass. Access Premium Content Big Law's International Tilt

The major U.S. markets have all lost head count among the Am Law 50. Chicago is down 890 lawyers; Los Angeles is down 540; Washington, D.C., is down 300; and New York is down 260.

The Chicago number represents an aggregate 20 percent contraction, led by 100-plus lawyer declines at DLA Piper, K&L Gates, Mayer Brown, Sidley Austin, Winston & Strawn, and McDermott, Will & Emery. Likewise, the LA contraction equates to almost 20 percent, and is led by a 100-lawyer decline at Latham & Watkins; an 80-lawyer decline at Paul Hastings; and 50-plus lawyer declines at Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer (based on the sum of the predecessor firms' lawyer numbers), Jones Day, and Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom.

The Washington and New York dynamics are different. Unlike the largely across-the-board declines in Chicago and Los Angeles, some firms there grew while others shrank. In Washington, for example, while Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr contracted by over 200 lawyers, Squire Patton Boggs by 170, and Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld by 100, others grew. Cooley; Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher; Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison; and Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan each added 60-plus lawyers.

In New York, the numbers show the major inroads made by non-native firms. Kirkland & Ellis grew by 175 lawyers, Gibson Dunn by 140, and Quinn Emanuel by 110, while many indigenous firms saw large declines, including Skadden by 220 lawyers, legacy Kaye Scholer (now combined with Arnold & Porter) by 170, Weil, Gotshal & Manges by 160, Debevoise & Plimpton by 100, Proskauer Rose by 90 and Willkie Farr & Gallagher by 80. Paul Weiss and Davis Polk & Wardwell are notable exceptions among the indigenous firms in that they grew, adding 160 and 75 lawyers, respectively.

London stands out among the international markets. Forty-six of the Am Law 50 now have offices there, an increase of six since 2008. These offices are home to 6,300 lawyers, making London the third-largest market (just 1,000 behind second-ranked Washington, and 2,400 ahead of fourth-ranked Chicago) by lawyer head count. London has 2,350 more Am Law 50 lawyers than a decade ago, or 1,300 more if one chooses to exclude Hogan Lovells and Norton Rose Fulbright from the increase. After London, there is a long tail of markets with sizable increases: Paris, Hong Kong and Sydney each added 500 lawyers; Singapore increased by 370; Mexico City and Munich each grew by 270; and Melbourne, Frankfurt, Sao Paulo, Milan, Toronto, Dubai and Madrid all added more than 200.

It is noteworthy that Am Law firms grew differently in international markets than in domestic markets. Unlike the more mixed results in New York or Washington, growth in international markets is consistent across nearly all firms. For example, 38 of the 40 Am Law 50 firms with offices in London in 2008 added lawyers. The enabler of such consistent growth is, of course, intensive lateral hiring from indigenous firms.

In total, 22 of the Am Law 50 shrank at home while growing abroad. A further 16 firms, for a total of 38, added fewer lawyers at home than they did overseas, thus increasing international operations as a portion of the total business. Big Law's international shift is broad-based, and not driven by just a few firms.

To follow a conversation on this subject between The American Lawyer editor-in-chief Gina Passarella and executive editor Ben Seal beginning Tuesday, April 30, register here:

To interpret the data, it's worth looking at how firms cluster when placed on a graph showing both domestic and international head count change since 2008. Group 1 includes the firms that come to mind when one thinks of fervent international growth: Hogan Lovells is the product of the 2010 combination of Washington-based Hogan & Hartson with London-based Lovells; Squire Patton Boggs merged in 2011 with Hammonds, a Leeds-based U.K. firm with a broad European presence; K&L Gates combined with Australian firm Middletons in 2013; Fulbright & Jaworski joined U.K.-based Norton Rose in 2013 to form Norton Rose Fulbright. These combinations produced international growth of 300-plus lawyers at each firm. However, for four of the five firms, this growth doesn't create partner subsidy issues because they are structured as vereins, thus sequestering each entity's profit pool for local distribution.

Group 2 includes firms that that would face more keenly the issue of growing cross-subsidies, to the extent that they operate with vestigial lockstep compensation systems. They all shrank by over 200 lawyers in the U.S. since 2008—Skadden by 460, and each of McDermott, Weil Gotshal, and Wilmer by about 300. While U.S. contraction alone would decrease high-profit U.S. operations as a share of total business, for five of the group—Dechert, McDermott, Akin Gump, Weil Gotshal and DLA Piper—this dilution has been deepened by the addition of 50-plus international lawyers.

Group 3 includes firms that are bucking the trend. With 200-plus lawyer growth in the U.S., these firms have all added more lawyers domestically than internationally. It's perhaps not surprising to find among this group the perennial strong financial performers of Kirkland & Ellis, Gibson Dunn, Quinn Emanuel and Paul Weiss. In this group, too, are Covington & Burling, Cooley and Perkins Coie. This troika share the distinction of each recording their strongest lawyer growth in their Washington, D.C., offices.

For Covington, this suggests a doubling down on its existing practice strengths in life sciences, financial services regulation and government. For Cooley, it's perhaps a regulatory tie-in to its life sciences practice. Similarly for Perkins Coie, D.C. growth may reflect the growing importance of International Trade Commission litigation and Patent Trial and Appeal Board proceedings to its technology and startup clients, and was accompanied by a doubling down on its strength in the West, with growth in Denver, San Diego, San Francisco and Seattle. Morgan, Lewis & Bockius is perhaps an anomaly in this group—much of its domestic growth came from the remnants of Bingham McCutchen; quizzically, Bingham's strong Chambers rankings in banking and finance, financial services regulation and bankruptcy/restructuring did not make the transition.

The Challenges Ahead

Legal market commentators have been pushing the need for firms to become more global for years. The logic seems to be that the business world is getting more global, so U.S. law firms should, too. This is dangerously simplistic, and worth unpacking.

First, this logic rests on the premise that clients prefer to source from one firm globally rather than to source from separate firms locally (which may be stronger in particular areas) and then integrate their services themselves. In business school parlance, this is referred to as preferring the "one-stop-shop" to the "best-of-breed" solution. The reality is that there are situations where each is the preferred client approach. Importantly, however, the one-stop-shop is preferred when a client feels no particular need to use local best-of-breed providers. This is the case for relatively routine work where many providers are considered capable, such as commodity work. For the differentiated work that elite firms seek to provide, it is neither logical nor commonplace for clients to choose the one-stop-shop approach.

There's also an underappreciated human element. Clients had well-established local counsel relationships in international markets before the U.S. firms arrived and grew. At many clients, local personnel get to decide which law firms to use. They have no particular incentive to use a newly grown U.S. firm whose name has no brand resonance and whose close ties to U.S. corporate personnel may be perceived as a way for "corporate" to impinge on their autonomy.

This leads the U.S. firms to focus their lateral hiring on partners perceived as having local client relationships that can be ported to their new firm. It's a small target group, creating aggressive competition. As a result, the business case for hiring the lateral isn't always fully tested and the compensation offered is often pushed beyond what's justified. Dicey business cases and exuberant compensation create poignant examples of the broader trend toward U.S. partners subsidizing the compensation of their international brethren.

Beyond lateral hiring, competitive intensity between U.S. firms is a major determinant of the financial performance of investments in international markets. More competition translates to lower volume (as the fixed pie of client mandates is split into more pieces) and softer price realization. The simultaneous international growth by so many firms has intensified competition overseas. To quantify by how much, we calculated a concentration index for Am Law 50 lawyers by city, akin to the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) from antitrust law (it is the sum of the square of each firm's share of the total number of Am Law 50 lawyers in the city multiplied by 10,000). As expected, the index shows that concentration fell for 23 of the 25 largest international markets; for 14 of these 23, the reduction was by more than 200 HHI points, which is the benchmark level by which the Federal Trade Commission considers an increase to show enhanced market power. A decrease of the same magnitude thus represents a significant loss of market power. In short, there is clear evidence that the Am Law 50's simultaneous international growth has disadvantaged firms economically by ceding bargaining power to clients.

Perhaps counterintuitively, the same intensification of competition—and hence ceding of market power to clients—has happened domestically. How can this be if the overall U.S. market has shrunk in terms of number of lawyers? Simply put, while the total number of Am Law 50 lawyers in all the major U.S. markets has gone down, those lawyers are now distributed across more firms. The effect on domestic competitive intensity and bargaining power is surprisingly close to that of its international counterpart: 21 of the top 25 domestic markets are now less concentrated than they were a decade ago. For 14 of these 21, the reduction is greater than 200 HHI points.

This analysis has two important corollaries. First, it debunks the widespread perception that the market is consolidating. The very opposite is true. At the individual city level—where rivals actually duke it out—the market is fragmenting. It also highlights a flaw in the strategy understanding of some market commentators. The essence of a successful strategy is to get away from competition as much as possible, because competition decreases volume and erodes pricing; the exhortation to individual law firms to look like other firms by adding offices and practices is the perfect obverse of sound strategy.

The Reckoning

It's going to happen. The business cycle will turn and profit pools will contract. Partner attention will be drawn to the lack of balance between partner compensation and economic contribution, and hence to international offices. Emotions will run high. Changes will be sought by U.S. partners on two dimensions: paring back offices internationally and aligning compensation systems more closely with economic contribution. There will be an intense questioning of firm leadership on these issues. Wise leaders are getting their responses, and their action plans, ready.

Hugh A. Simons, PhD, is formerly a senior partner and executive committee member at The Boston Consulting Group and chief operating officer at Ropes & Gray. He writes about law firms as part of the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program. Contact him at [email protected] Bruch is a director at ALM Legal Intelligence. He is ALM's principal analyst for the legal market and is the director of the ALM Intelligence Fellows Program. Contact him at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Greenberg Traurig Litigation Co-Chair Returning After Three Years as US Attorney

3 minute read

Blank Rome Snags Two Labor and Employment Partners From Stevens & Lee

4 minute read

12-Partner Team 'Surprises' Atlanta Firm’s Leaders With Exit to Launch New Reed Smith Office

4 minute read

After Breakaway From FisherBroyles, Pierson Ferdinand Bills $75M in First Year

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1With New Civil Jury Selection Rule, Litigants Should Carefully Weigh Waiver Risks

- 2Young Lawyers Become Old(er) Lawyers

- 3Caught In the In Between: A Legal Roadmap for the Sandwich Generation

- 4Top 10 Developments, Lessons, and Reminders of 2024

- 5Gift and Estate Tax Opportunities and Potential Traps in 2025 for Our New York High Net Worth Clients

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250