What Helps the Super Rich Maintain Their Success?

Five years since its debut, the Super Rich list has a familiar look, as the elite law firms stay elite.

April 23, 2019 at 09:54 AM

6 minute read

Credit: Egle Plytnikaite.

Credit: Egle Plytnikaite.

For law firms, just like the rest of America, there's no better path to amassing wealth than to already have a healthy share.

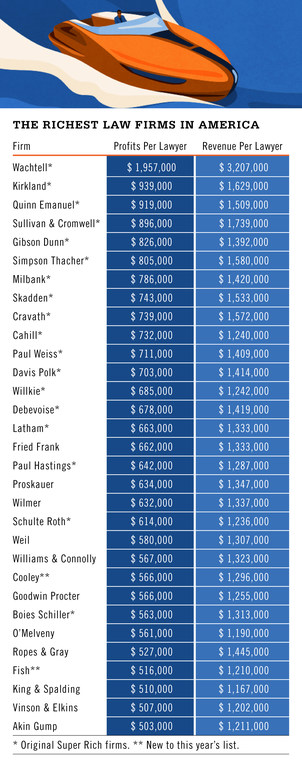

Of the 20 firms that comprised The American Lawyer's first Super Rich class in 2014, all but two have carried their status forward through the years to maintain a spot on our 2019 list, which has since expanded to include 31 firms. Together, they represent the richest of the rich. The way we define this elite group has changed over the years (firms must now post revenue per lawyer of at least $1.1 million and profits per lawyer of at least $500,000), but its founding members have largely held their places. Gretta Rusanow, head of advisory services for Citi Private Bank's Law Firm Group, says it's a sign of the "stickiness" the wealthiest firms experience at the top end of the law firm class structure, even in a year when nearly everyone took a step forward.

Leverage the Am Law 100 data with firm comparison and key performance data, exclusively on Legal Compass. Access Premium Content

Leverage the Am Law 100 data with firm comparison and key performance data, exclusively on Legal Compass. Access Premium Content "They have the financial resources to be making different decisions and investments than firms not performing at that level," Marcie Borgal Shunk, president and founder of the Tilt Institute, says. "So where an Am Law 200 firm may have to selectively choose among different priorities, the benefit of having deeper pockets is that you can be more exploratory, invest in different options and try more innovation."

This year's list is led by Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, whose profits per lawyer ($1.957 million) are more than double the closest firm, even among an exclusive club, and whose revenue per lawyer ($3.207 million) nearly matches the feat. Cooley and Fish & Richardson represent the newest additions to the club. (The only firms from the 2014 list that failed to make it this year are Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft and Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton.)

In the past five years, the 31 Super Rich firms grew RPL an average of 20 percent (compared with 14.6 percent for the rest of this year's Am Law 100), and their PPL grew an average of 26.2 percent (compared with, again, 14.6 percent). Even during a period of strong growth for the industry as a whole, these firms are outpacing the competition.

In some ways, these firms are immune to challenges others face. A lengthening collection cycle was one of the few negative markers for law firms in a successful 2018, Rusanow notes, but the most profitable firms managed to shorten their own collection cycles.

In some ways, these firms are immune to challenges others face. A lengthening collection cycle was one of the few negative markers for law firms in a successful 2018, Rusanow notes, but the most profitable firms managed to shorten their own collection cycles.

The Super Rich are able to differentiate their brands, she says, by offering clients something different from the bevy of multidisciplinary, large-scale firms that dot the landscape.

"They tend to be focused on a handful of practices that they're extremely strong at," Rusanow says.

Fish & Richardson, for example, managed to join the list this year on the back of its focused intellectual property practice, proving that to gain entry to this select group, less is often more.

"We're well known as an IP specialty firm and as a very good one, and it's a field that is highly valued by our clients," says Peter Devlin, the firm's president and CEO. "They send us their toughest, most complex and highest-stakes work, and that has driven our financial success."

And for firms that have made it into the upper tier financially, that status means they are well-positioned to leverage their financial success to grow in the future.

"As in any industry, the more cash that you have, the more options you have," Shunk says. "And if you're making the right decisions, it can work to your benefit."

There might be something else working in favor of the elite staying elite, some who follow the industry closely say: culture. It may not be the defining reason that the list looks so familiar five years later, but Deborah Farone, a consultant who served as chief marketing officer at Debevoise & Plimpton and Cravath, Swaine & Moore, both of which have been among the Super Rich from the beginning, thinks it plays a bigger role than is often credited.

"Culture has a huge implication for why firms stay successful, and if I were a managing partner I would be focusing not just on strategic planning and practice planning, but also how do I keep a strong culture where people feel supported and feel like they're growing, and partners feel like they're treated well and appreciated for their work," Farone says. "Those things are sometimes undervalued, but we're seeing that they're so vital."

In an era of seemingly constant lateral movement, maybe the key to staying exceedingly profitable as a firm is to develop a culture that keeps exceedingly profitable partners in place.

"While we think and read a lot about the headline lateral moves, firms will also tell us that 30 to 40 other partners may have been approached and made the decision not to go," Rusanow says. "When you ask those firms why that's the case, they talk about their strong culture."

Some of the 31 Super Rich firms have contracted their partnerships in recent years, but on average they added 20 partners in the past five years, including six equity partners. The most profitable firms have a better success rate in hiring laterals, Rusanow says, largely because they add lawyers who enhance the well-defined brands they've already built.

Those brands have been developed carefully over a period of years, but there may be change on the horizon that could unseat some of the country's most profitable firms if they aren't adequately prepared. As Shunk sees it, the generational shift that will see millennials take over the decision-making reins could pose a threat to the assumed status of the industry's elite, who have long been on the receiving end of high-value business brought in, in part, by that status.

"There's a time stamp on it, an expiration date on how valuable that brand is going to be," Shunk says. "Are they offering some authenticity? Are they giving back to the community? Do they have a mission?"

Maybe in another five years we'll have a better sense of whether culture begets profits or the other way around.

Email: [email protected]

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Government Attorneys Face Reassignment, Rescinded Job Offers in First Days of Trump Administration

4 minute read

Energy Lawyers Field Client Questions as Trump Issues Executive Orders on Industry Funding, Oversight

6 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Doug Emhoff, Husband of Former VP Harris, Lands at Willkie

- 2LexisNexis Announces Public Availability of Personalized AI Assistant Protégé

- 3Some Thoughts on What It Takes to Connect With Millennial Jurors

- 4Artificial Wisdom or Automated Folly? Practical Considerations for Arbitration Practitioners to Address the AI Conundrum

- 5The New Global M&A Kings All Have Something in Common

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250